13 Blitz bomb disposal memoirs of Sgt Brian Moss, Royal Engineers, WWII

Danger - Unexploded Bomb! WWII London Blitz.

The story of one man’s brave war against unexploded bombs in wartime London, during the 1940 Blitz: Brian Moss, Platoon Sergeant in 233 Field Company, Royal Engineers.

"Imagine the shock when your pick clangs against steel. You wonder if you have started the clock ticking. On your knees, you use a trowel to carefully uncover the bomb."

YouTube channel - Loads of my own videos - Dunkirk Mole, Gold Beach, more ...

Feedback/reviews in Apple Podcasts - Thank you.

Interested in Bill Cheall's book? Link here for more information.

Fighting Through from Dunkirk to Hamburg, hardback, paperback and Kindle etc.

"We saw the vapour trails of an immense bomber fleet which was, by then, almost overhead. We ran for the trenches that had been dug across the field."

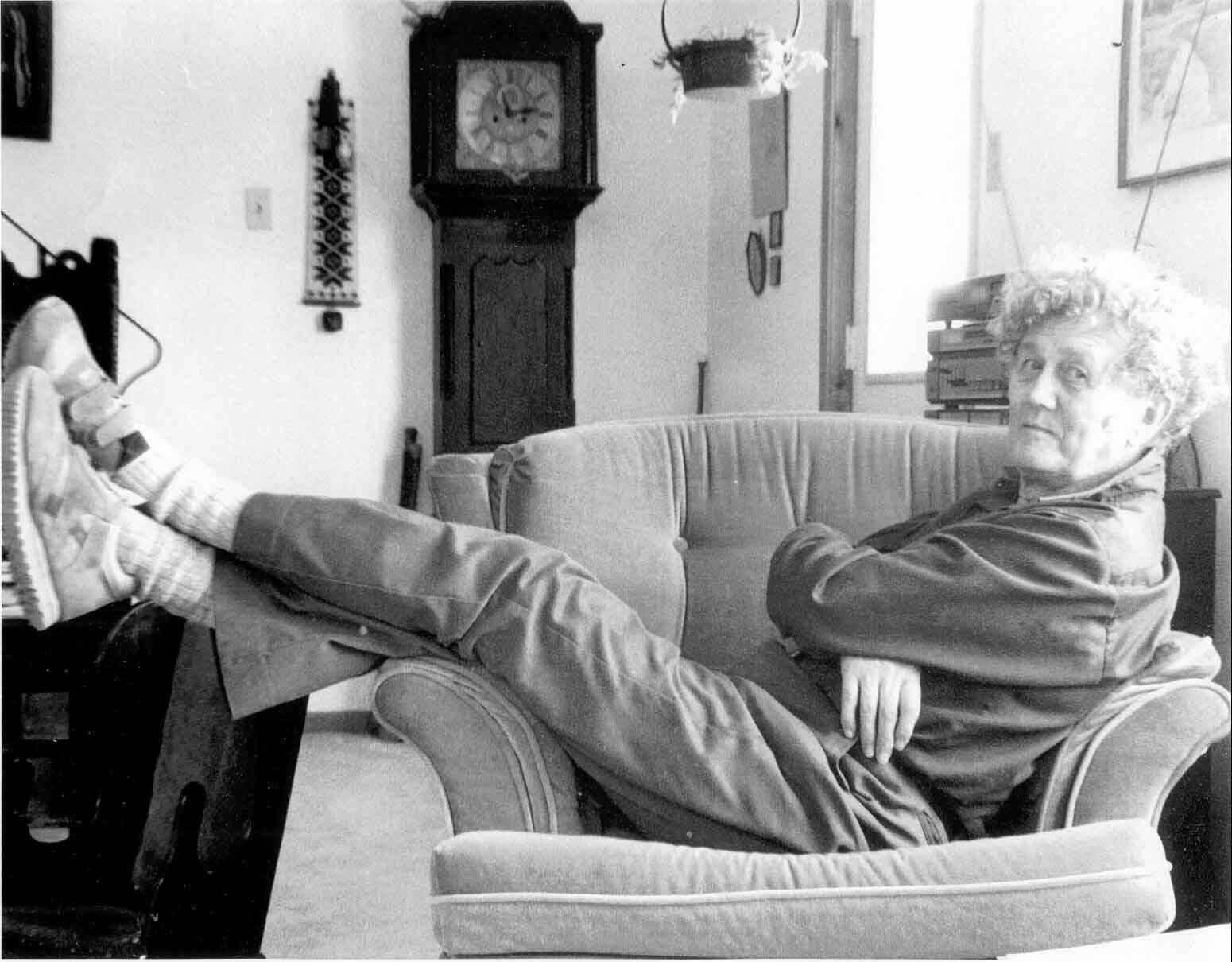

Brian Moss in Nova Scotia 1998

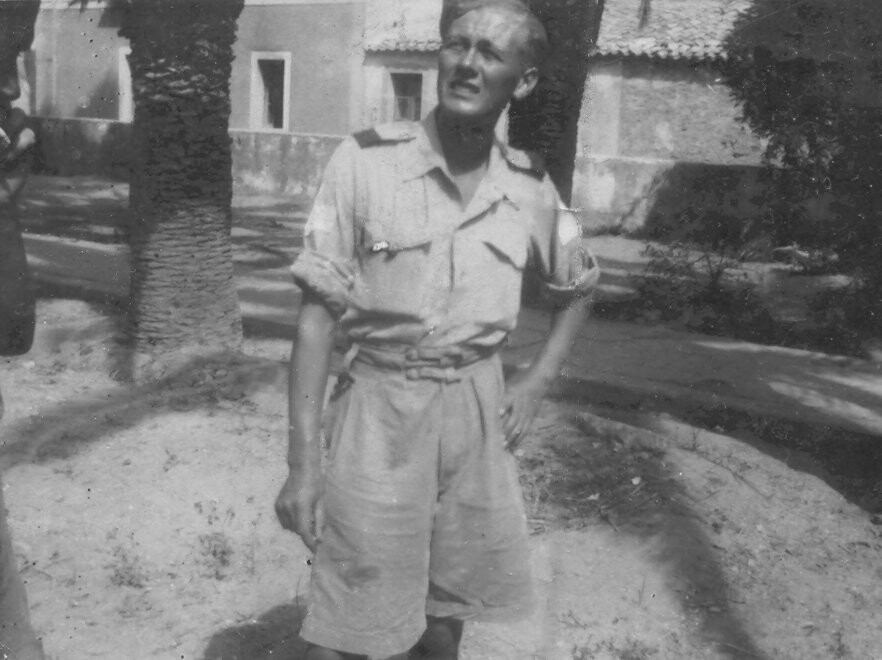

Brian Moss Sicily 1943

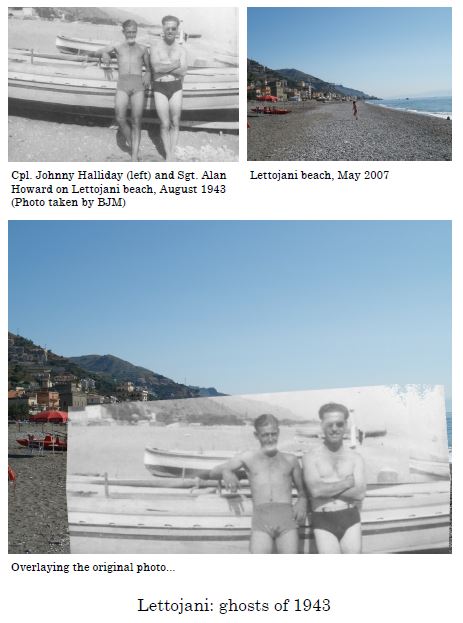

Lettojani then and now WWII

45 Twyford Ave, where Brian stayed for his period of duty during the London blitz in WW2

Brian Moss with a diffused bomb. Note the opened fuse pocket

Listener contribution - from MacNerd93 - James W Mann - My grandad during WWII. He's the first guy on the left. He was in bomb disposal, later serving in the North African Campaign WW2

Bomb destruction in WW2 London. Tragic history!

Bomber flying over the Thames river in WW2 London

Iconic view of St Paul's cathedral rising majestically above the surrounding destruction

St Paul's cathedral believed to have been a navigation landmark for the enemy, so largely survived the WW2 Blitz

onslaught

Fighting Through podcast episode 13 - Danger – Unexploded bomb!

This is a WW2 history podcast about Brian Moss memoirs.

More great unpublished history!

This is the story of one man’s brave war against unexploded bombs in wartime London - during the 1940 Blitz – Sergeant Brian Moss, WW2

"I planned the day eating blackberry suet pudding!

"I retired to bed early one night. I was sleeping in the kitchen when I awoke suddenly and looked at my watch. It read: 9:45. Then I heard the bombs coming. This is it, I thought.

"Imagine the shock when your pick clangs against steel. You wonder if you have started the clock ticking. On your knees, you use a trowel to carefully uncover the bomb.

Hello again and a very warm welcome to everyone.

I’m Paul Cheall, son of Bill Cheall whose WW2 memoirs have been published by Pen and Sword – in FTFDTH.

The aim of these podcasts is to give you the stories behind the story. You’ll hear memoirs and memories of veterans connected to Dad’s war in some way – and much more.

WW2 history Podcast Feedback

I’d like to thank a listener for his recent feedback:

“I'm from Lake Tahoe California. My grandfather and his brother fought in the pacific war. We lost my grandfather’s brother on December 7th 1941 on the U.S.S Oklahoma at Pearl Harbour. I am named after him. James Williams.

I want to express my thanks to you for your story telling style and for the pride you so obviously hold for not only your father, but all these incredible men that made us all free today.

God bless you and all our heroes alive and past. These stories are true tear making experiences.

I love all our allies of WW2. Thank you again.

Well, James thanks so much for getting in touch. And my goodness how tragic about your great Uncle. Reading your email reminded me of how Dad felt a great affinity with the allies. In his memoir he said:

“In the spearhead there were young men from all over the British Isles. I knew that the brave Canadians wanted to avenge Dieppe and that the American boys needed to see that the war with Germany came to a conclusion so that they could settle their outstanding account with Japan over Pearl Harbour. They would give their all, every one of them, and whilst sharing such dangerous experiences, would create an enormous bond of comradeship.”

I’ve got some more feedback on a previous podcast, the one about little ship the Bee. You might recall the story told by engineer Fred Reynard about the rescuing of troops at Dunkirk. The Royal Navy was commandeering the Bee.

The officer told them about Dunkirk and said, "Ever been under shell-fire?"

"Ever heard of Gallipoli?" was Reynard’s retort.

He and his crew took the Bee to Dunkirk with a navy sub-lieutenant nominally in command.

Pause

If you look at the shownotes for that podcast, no 12, at bit.ly/TheBeeShip you’ll see a great photo of Fred and the rest of the crew on the Bee. There’s a look of fearless defiance about them as if they’ve been around the block a bit and here’s why I think that is …

I recently heard from Helen Westbrook,

I’m the grand-daughter of the late Fred Reynard. My family, including my brother and sister, thoroughly enjoyed listening to Gramps fascinating story on your recent podcast. We all have fabulous memories of a wonderful man, who lived an amazingly full life. He also left another wonderful war diary from WW1 relaying his experiences from Gallipoli!

Well, listeners, I’ve read just a short passage from that diary and it’s … breath taking. The great news is that Helen is happy for me to make it into a podcast. So I hope to do just that in the not too distant future. I’m also expecting you’re in for a real treat.

You know, I can’t believe how lucky I am finding all this unpublished history and even luckier that I can help share it with other people.

Mike’s letter

Mike wrote:

My father, Brian Moss, was a Platoon Sergeant in 233 Field Company, Royal Engineers, England, attached mostly to the East Yorks battalion but also at times to the Green Howards. I recognize many place names in your father’s account.

My father first joined 50 Div after his arrival in North Africa in June 1942. His active involvement in the war ended in September 1944, when he was blown up by a butterfly bomb in Nijmegen. He spent most of the next year in hospital.

My father’s war had started in bomb disposal during the London Blitz, and his experience with bombs and mines led to his being appointed to develop a desert mine school for infantry in 69 Brigade. If you are still in contact with any former comrades from Green Howards (or East Yorks), I’d be very interested to reach them.

During my research I’ve located a former tank commander of the Hermann Goering Abteilung in Sicily - Dad and two of his men snuck up and blew up three of his unit’s tanks when they were parked in a land south of Primasole Bridge on July 16, 1943).

Another contact has been with the son of the Marine officer who I believe commanded the same landing craft in which dad travelled to Gold Beach!

Mike Moss, Canada

So, listeners, as a result of Mike’s fascinating contact we exchanged correspondence and he kindly sent me a full length memoir his late Dad had written.

You may recall Brian Moss being in action in North Africa and D-Day, both gripping narratives in previous podcast episodes – Nos 2 and 3 for anyone who wants to return to them. It was reading through Brian’s meticulous description of blowing up an anti-tank ditch during the battle of Wadi Akarit in Tunisia on 6 April 1943 that drew me to another passage from his excellent memoir, which has not yet been published although in my own humble opinion it deserves it.

The intricate detail that Brian goes into is every bit as absorbing as any piece of fighting action. Listeners I’ll warn you now that parts of it get just a little bit technical but if there are terms you don’t understand I’d suggest you gloss over them.

Above all, let yourself become immersed in what I think is as fine and rare an example of writing of its kind that you’re ever likely to come across – so here goes.

The story starts in 1940, just a few months after the Germans invaded France. And the Luftwafffe are making their presence felt bombing the poor Londoners in what was called the Blitz. Brian has been called up to fight ….

Brian’s war starts in London in Bomb Disposal, WW2, Royal Engineers

All of a sudden we were put on a train bound for London. We arrived during the night of 17th September 1940, in the middle of a savage air raid. Shells were bursting in the sky above us. At Paddington, we were put in coaches and taken to Creswick Road, Acton. We entered a large residence, Torkington House, which although a big place, seemed much smaller when three hundred men were crammed inside.

I was billeted in a downstairs room at the rear, along with some thirty other men. The lone toilet at the end of the corridor outside was busy all night while bombs fell and anti-aircraft guns thundered all around us.

Next morning, we assembled outside. We marched off, turned a corner and found ourselves in a cul-de-sac leading to a large grassed playing field of about ten acres. We marched across it and into some wooden pavilions. Here, a rudimentary breakfast had been prepared, which we ate with gusto in the midst of cricket pads and goal posts!

Immediately after breakfast, we were paraded in Sections, and detailed off in batches of twenty men. Each Section was now allotted three houses for billets in Twyford Avenue on the other side of the playing field.

Before we could move off to our billets, the sirens wailed again. To the east we saw an extraordinary sight. It was as if someone had taken a piece of chalk and drawn hundreds of white lines across the blue sky, all emanating from one point on the eastern horizon, radiating and diverging as they approached.

These were the vapour trails of an immense bomber fleet which was, by then, almost overhead. We ran for the trenches that had been dug across the field. Now we could see fainter trails weaving a complex pattern through the bomber trails, and we knew that our fighters were up there, too. The armada turned south, and with the sound of a long indrawn breath, the first bomb load fell on the other side of the river.

That night, I slept at No. 45 Twyford Avenue. The next morning, we were paraded in the street in front of our billets and marched to Torkington House.

Here, the Commander Royal Engineers, (CRE) London Area addressed us. “During the last 24 hours,” said the Colonel, “one thousand unexploded bombs have dropped in London. They have a new type of electric fuse, which we know little about. You’ll be issued with axes, picks, shovels, ropes, handsaws, and rubber kneeboots. Go to it, men, and good luck!” We were to be known as 719 Bomb Disposal Company. Untrained as we were, Bomb Disposal was to be our job.

We were divided into Sections of twenty-four men each. I was given F Section and promoted to Lance Sergeant. Our Section Officer was to be Lt. Ewart. Our billets were reshuffled so that sections occupied individual houses and within 24 hours we had visited our first bombs and had obtained our first Elaz C15 fuses.

I was designated Draughtsman Architect, and this, together with my new rank, gave me 9 shillings and sixpence (47½p), I don’t know, 50c US? per day which was more than adequate for my needs. Listeners it’s interesting to reflect that my Dad as an infantryman earned 2 shillings a day, less than a quarter of that sum!

I was also designated Recce Officer and in this role visited Acton Police Station every morning. The Station Officer and I used to visit all incidents that had occurred during the previous night, and would then decide which bombs had exploded and which had not.

This is not so silly as it sounds, since the mere arrival of a bomb in a house can cause the lot of it to fall down, even if the bomb didn’t explode. The expert (i.e., me!) would deliberate on this point, and only once did I get it wrong. On that occasion, the darned thing went off four hours after I had certified that it had already exploded!

Bombs came in various sizes, e.g., 50 kg; 250 kg; 500 kg and 1000 kg. Of these, the 250 kg was the most common. The German electrical fuse, made by Rheinmetall Stalhein, was part of an integral ‘weapons system’. It was not only linked with the bomb but also with the aircraft. The system had been previously tested and proven serviceable in the Spanish civil war.

We encountered many fuse types but all were of the same size and fitted in the same fuse pocket. Merely held in by a locking ring, they were designed to be quickly and easily interchangeable.

The basic system was this: the fuse had a plug receptacle top that was wired to a plug in the aircraft’s electrical circuit. The bomb-aimer would flick a switch to arm the bomb just before release. This switch passed a current via the plug to a condenser in the fuse. This condenser was connected to a second condenser via resistors that permitted only a slow passage of potential (Listeners – sort of electrical charge).

Before charging, the bomb was completely safe. As it fell away from the aircraft it was still safe because the potential had not yet leaked from the charging condenser to the second (firing) condenser. As soon as the charge had accumulated sufficiently in the firing condenser, the bomb became fully sensitive.

This would occur when it had fallen a few thousand feet below the aircraft. Obviously, it was important that the bomb-aimer did not forget to flick the switch, and that the aircraft did not attempt to bomb from too low an altitude, or else the firing condenser would not be properly charged.

These two points were to result in the high proportion of bombs that did not explode. Inevitably, these became labelled as UXBs (unexploded bombs), although to us, a UXB was a bomb that was going to explode at some unknown instant.

Detonation was achieved in the following manner: the firing condenser was connected to a pellet of material that would burst into flame on the passage of a small electrical current via two trembler springs.

Any shock, such as the bomb hitting the ground, would tremble the springs, effect the contact and cause the pellet to burn. The flame from the pellet would ignite a micro-delay fuse of powder and the delay would allow the bomb sufficient time to penetrate a structure before exploding. The delay fuse would in turn fire directly into a small steel thimble-shaped detonator that was screwed into the base of the fuse. The detonator was filled with a pink wax (penthrite), a highly sensitive compound that I used to remove by melting it out with warm water.

The detonator itself was fitted snugly into ‘pineapple slices’ of picric acid that filled the remaining depth of the fuse pocket, across the whole width of the bomb. The picric acid stage was designed to boost the action of the detonator and to ensure that the entire main filling of the bomb would explode.

The main filling was usually, but not always, liquid TNT. During manufacture, this was poured in while hot, and hardened upon cooling. The bomb was fitted with light steel fins that tore off on impact, exposing the filler cap at the tail. This filler cap was the full diameter of the bomb, and could be unscrewed by tapping with a hammer and chisel.

I would unscrew the cap, then hammer and chisel into the TNT and smash out half a dozen fragments of it. Then I’d put an oily rag into the broken fragments of TNT and ignite it. The TNT would burn noisily with a lot of black oily smoke. One day I realised that a booby trap could be cast into the TNT filling and I never burned out a bomb again. Later we heard that casualties had often occurred in this manner. When I think of the things I did in those days my blood runs cold. It was not only myself I was exposing to danger.

All fuses were built into the same aluminium body. Identification was easy. Upon the head was stamped Elaz Cx, where ‘x’ was the number of the fuse in question. The simple impact fuse was the No. 15, and was stamped with a figure ‘15’ within a circle. A sneakier device was the Elaz C17. The number 17 became associated, in my mind, with double-dealing, craftiness and death. It probably still does today.

The number 17 was the first clockwork fuse. The initial shock was intended to start the clock, which fired the charge after a certain period of time. Many clocks were not started by the shock of hitting the ground, but could be started later by a tap with a shovel. Some clocks stopped after a few hours, but could easily be restarted at a later time. So, with a 17 fuse, you could be dealing with something that, if it was running, could explode at any instant, and if not running, could easily restart with only seconds to go.

In those days, the normal drill was to immediately slap a discharger onto the fuse head. I still have my discharger; Crabtree had made it in a hurry. The discharger performed two functions. Firstly, it connected the two electrodes in the fuse head, thus discharging both condensers. Secondly, it could be used for withdrawing a difficult fuse stuck tightly in the pocket. You can guess the enemy’s riposte; the fuse was later redesigned to detonate if the electrodes were connected.

Another gambit we used was to drill into the top of the fuse and pour in molten paraffin wax. This would set around the tremblers, and prevent them from moving. This, too, became a very dangerous game when the enemy realised what we were up to. I could never understand why they did not stamp 17 fuses with a 15, or use other confusing (no pun intended) stampings. I have removed many fuses, but never a 17.

But they played it straight. Fuse removal was surprisingly easy. At least until the Zus40, in which case the officer was supposed to remove the fuse.

The arrival of the Zus40 could have been predicted. It was a small device that fitted under the fuse and detonated the bomb. Therefore, we were now in a situation when fuses could no longer be removed with any degree of confidence. One response to this was ‘Freddy,’ a device that we would clamp onto the fuse head and set in motion. We would then retire and Freddy would pull out the fuse all by himself. After use, Freddy had to be taken to the National Physical Laboratory, to be recharged.

Alternatively, we could dig out the bomb with the fuse still inside, and take it intact to Hackney Marshes for destruction. After several trucks disintegrated en route, this practice was no longer favourably regarded. Another solution was to evacuate the neighbourhood, and blow up the bomb in situ. My own experience included all of these measures.

Although I never used it myself, a trepanning device could be used to cut holes in the bomb case, allowing steam to be injected, thus melting and removing the main charge. However, the picric acid pellets still remained in the fuse pocket, and could still kill anyone in the immediate vicinity if the fuse were activated.

My Section F operated in the London area along the North Circular Road from Ealing and Wembley to Finchley and Wood Green, covering as far west as Greenford and Harrow. Meals were cooked on the Sports Ground, and taken out to the job site in various vacuum containers. Our vehicles were brightly painted a post box bright red colour. Everyone made themselves scarce when they saw us coming – we might have been carrying a ticking bomb on board!

We worked from 7 am to 5:30 pm. At night, the lads got polished up and went downtown. There was only one cinema in Acton. The film changed on Thursdays and I would make sure I was in the cinema early. Usually, a slide would appear over the film: “The air raid warning has just sounded.” No one took any notice; it was the same every night.

A taste of the WW2 Blitz, London. Second world war WWII History podcast

At the end of the film, I would emerge into pitch-black streets, illuminated only by gun flashes. One night I saluted a bus conductor by mistake; his white cuffs looked like a Rear Admiral’s braid. Leaving the cinema, I’d turn right and start walking back to Twyford Avenue. As I recall this, I am taken back to a typical bombing raid:

A spot of yellow light suddenly appears in the sky. It disappears. Then it reappears, somewhat brighter. It’s getting bigger. A second yellow light flares out in the sky half a mile from the first, then a third, and then a fourth. The string of flares produced a sickly yellow glow over Acton. The enemy’s target is Park Royal again, an industrial area. A bomber approaches, its engines making the sound, “Um, Ah Um, Ah Um”.

Suddenly, I’m startled out of my wits by the flash and crash of a 3.7 battery that I didn’t even know was just beyond the park railings. The shells go rumbling up into the heights and explode faintly, “spat, spat, spat”. Then comes the long indrawn breath of an exploding bomb. I crouch at the side of the road and, although I know the bomb has exploded, I can’t be sure that I heard it. The guns crash again, and I curse them because they seem so futile.

I turn into Twyford Avenue, tripping over someone lying on the ground, and I hear the shell fragments spinning down from the heights and bouncing on the road. Twyford Avenue doesn’t look the same as it did when I left to go to the cinema. One of the houses has been demolished, and is now a black shapeless mass lying half way across the road.

A broken gas pipe flares in the wreckage in which rescue men work patiently. The flares are lower now and the wind has brought them nearer. The first one dropped is very low; in fact, I can see its parachute above, illuminated by the flare. A gob of liquid fire drops away, and now there are only three flares in the sky. A red glare suddenly erupts over Park Royal.

I nip smartly into No. 45, and surprise, surprise: everything is going on just as if nothing had happened outside. Some men, even at this time, are preparing to go downtown. They won’t be back before dawn, and I make a mental note to look out for them on first parade.

I retired to bed early one night. I was sleeping in the kitchen at No. 45 when I awoke suddenly and looked at my watch. It read: 9:45. Then I heard the bombs coming. This is it, I thought. The awful shriek came closer and closer. The house heaved and, in the darkness, I put out a hand to hold up the wall I knew would come crashing down on me.

Nothing did fall on me, but I could hear masonry crashing around me everywhere. The window frame appeared to be swaying about inside the room. Dr Jacka appeared at the door. Jacka had been made medical orderly and was known to us as Dr Jacka. He wanted to know if I was okay.

I struggled out of bed and went to investigate. One bomb had fallen in the back garden of No. 45 and had severely damaged the back of the house. The next bomb in the stick had missed our house but had hit the one across the street. Jacka and I stood at the front door trying to see what had happened. In the pitch darkness, the row of houses across the road looked like a row of teeth with a tooth missing. What remained of the house opposite was only one quarter of its original height. It was also on fire.

I started walking towards the street but something caught my eye. Something was on our railings. With horror, I realised it was a female body that had been flung across the road and impaled on the fence. I thanked God for the darkness. We all did what we could for ten minutes until the appointed teams arrived. As they took charge, I tripped over something in the gutter on our side of the road. It was a second female body, headless and limbless.

I was told later that twelve women had been in that house; foreigners, it was said. It had been previously rumoured that light signals had been seen at night from this house. This was probably quite erroneous. I suspect that my opinion of the enemy then was far less charitable than it later became when we found we had more in common with the front hogs of the Wehrmacht than we did with our own base camp types; much more, in fact.

On non-cinema evenings, I would go to ‘Jack’s Place’, a dingy café with a fruit (slot) machine. I gave Jack, the bald owner, instructions to bake blackberry suet puddings for me. I would sit in the corner and eat my pudding, while thinking about what would have to be done the following day.

The night of 14-15th November was one of significance. At around midnight, the whole company was in a state of anger and excitement. Telephone calls had revealed that Coventry was under attack. Coventry was the home of many of our men. Quite a few had already gone to the North Circular Road and hitched a ride home, wholly without authority, of course.

When morning came, we were about 20 men short. Others knew that their families had been killed and their homes destroyed. I cannot recall any action being taken against the absentees, except in the case of Wyatt, who kept absenting himself, eventually breaking out of the guardroom at the rear of Torkington House.

My personal collection of fuses grew. The fuse number indicated what the bomb would or should do after striking the ground. Delay before detonation is most important in a demolition or anti-shipping bomb. Instantaneous detonation is desirable in a high capacity land-mine type of weapon; a land mine could wipe a whole street off the map.

Penetration would vary with the soil. It was the least in gravel or non-homogeneous material. In London clay, penetration was maximal. Upon digging about six feet deep, we would usually find the fins that had been torn off.

The manner in which they came off was one of the factors that guided the path of the bomb below ground. Most bombs seemed to be fairly stable in their path until something, probably loss of velocity, made them tumble, much like the 0.223 bullet does in flesh.

A typical bomb pattern would be a hole in the ground, below which the bomb would penetrate reasonably vertically for about twenty feet, and then it would shoot off sideways for another ten feet or so before coming to rest.

Our first problem was where to sink our shaft. For the sake of speed and efficiency, we obviously sank shafts of minimum diameter. However, small shafts could easily miss the bomb. It might seem logical to follow the bomb hole. Some teams did this, but finished up with an extremely dangerous shaft that wandered all over the place.

Much judgement was required in deciding where to place the shaft. Even divining was tried, such as used in searching for underground watercourses. I recall that the Deputy Borough Engineer of Tottenham became involved in this mysterious art. Sometimes a squad would dig for weeks and not find the bomb.

One of our teams removed a stick of bombs from Wall’s meat factory. After this, for the rest of our stay in London, we were sent a daily supply of free meat pies. For some reason I can’t recall, I visited Acton Police Station one day. In the yard outside stood a vehicle containing a beautiful parachute flare that had not gone off. Without delay, I pulled out my locking ring spanner and removed a No. 26 fuse, painted red.

When the specialist officer arrived later, he would subsequently report to CRE that the enemy was now dropping unfused weapons!

In my earlier description of the fuse, I mentioned the detonator (or gaine) screwed into the base. One day, I took off a gaine that did not contain penthrite wax. All it held was a folded piece of paper bearing a note written in a language I didn’t understand. I handed it in, and was later told that it was a message from a Polish worker, apparently enslaved in a munitions factory.

On October 26th, I visited 36 Northfield Avenue, Ealing. We were now just able to deal with a 250 kg bomb that had fallen there on Oct 1st. The bomb had hit something really solid and had scarcely penetrated at all. On the following day, we defused it and removed the black plug.

The main filling was not TNT. It was a greyish white powder, which smelled of mothballs. This was ‘hexamite’, the ultimate explosive. We were told not to touch it or we would get a dreadful skin disease. So, with that, we wore heavy gloves, and tipped the stuff into a dustbin for the experts to deal with.

All this time we were expecting to hear that the enemy had landed in Kent and Sussex. As the weeks went by, the view was expressed that he was waiting for the spring. Some of the local families in Twyford Avenue, who had stayed rather than evacuate themselves, offered to provide baths for servicemen. L/Cpl. Cotton of HQ and I were told to report to No. 115 Twyford Avenue.

Alternate nights were arranged for the pair of us to bathe, and so I arrived one evening and introduced myself to Mr and Mrs Townsend. They were a very pleasant and hospitable couple, and my invitation extended not only to baths, but also to dine with them for suppers. As you may perhaps have guessed, they had two daughters! Pamela was chasing an RAF type at the time; Betty was older and unattached.

A lifetime later, in July 1942, I happened across a piece of paper blowing across the desert. I retrieved it to find it was the centre page of Picture Post. The photo portrayed a group of Auxilliary Territorial Services (ATS) girls.

Among them, I thought I recognised Betty Townsend. So I wrote to her mother, asking if I was correct. She wrote back and confirmed that Betty had joined the ATS and was in Nairobi. That was the last I heard of the very helpful Townsend family.

Cpl. W. Fern of my Section once borrowed 50 shillings from me and then went sick. I never saw him again. I suppose at 5% interest, he would now owe me more than £19.40!

In the first week of October, I was instructed by Lt. Ewart to take the men to Wood Green. On September 10th, a stick of five 250-kg bombs had fallen, four in or near Wolves Lane, and one in White Hart Lane. We set about working on all of them.

After having spent days and days digging down and finding nothing, imagine the shock when your pick clangs against steel. You wonder if you have started the clock ticking. On your knees, you use a trowel to carefully uncover the bomb. You expose its end and can see it is a 250. You kneel beside it and you whisper to it, man to man. You try to persuade it that it only has a 15 fuse because, very often, it does.

We defused the bomb in White Hart Lane on October 9th. It had a No. 15 fuse. The bomb itself was removed to Hackney Marshes for demolition. At this time, following a series of disasters encountered while transporting bombs, we received orders that henceforth, all bombs were to be blown in situ. With this in mind, we worked on the remaining four bombs until all was ready on the morning of October 20th.

I clearly recall J Dixon, a small, scruffy chap, continually shouting to me from the bottom of the hole in the Recreation Ground that he could hear his bomb ticking. Every time I went down to listen, I heard nothing. Not a sound. One can well understand how a lively imagination can run riot at a time like that.

On this occasion, we laid a circular wall of sandbags around each hole to contain the blast. On average, the bombs lay at a depth of twenty feet. Each bomb was prepared for blowing with a one-pound slab of guncotton (6” x 3” x 13/8”), complete with guncotton primer, detonator and 4 minutes of safety fuse. I lit the first fuse. Crouching down with a Special Constable behind the roadblock (to stop traffic from entering the road), we saw sandbags and black smoke rocketing skyward and felt the ground kick under our feet. The landlord of the pub on the corner was pathetically grateful that his premises could open again even though we had just blown the front off it!

I dashed from one bomb to another in my 15 cwt. Guy truck, detonating each one in sequence.

Many, many thanks to Mike Moss for kindly allowing me to share it with you.

I want to say thank you to everyone for your support by way of feedback or listening. If you want to comment or share in any way you can do so via the contact page at ftp.co.uk.

Full show notes including photos and show transcription are at the web site or for a direct route for this show go to bit.ly/FightingThroughBomb.

I'm Paul Cheall saying

Bye bye now!

PS

We were to make a landing undetected I thought, but I thought too soon. Another 50 yards then hell let loose, a hail of machine gun and rifle fire swept through us. Now it was a case of every boat for itself. The Turks had placed barbed wire just under the water and the boats stuck fast and the soldiers were soon wiped out. My boat was lucky to find a gap through which we passed to the beach and scrambled out.

Fred Reynard, A Gallipoli story, 1915.

PPS

Mike Moss is keen to hear from anyone who has a connection with his Dad, but particularly from Corp W Fern, who owes him 50 bob!

This was a WW2 history podcast on Brian Moss' memoirs, WWII

Featured Episodes

If you're going to binge, best start at No 1, Dunkirk, the most popular episode of all. Welcome! Paul.

PS. Just swipe left to browse if you're on mobile.