2 North Africa WW2 - The Battle of the Wadi Akarit in Tunisia

Second World War Veteran memoirs of the 1943 desert, WWII. Three veterans' accounts of one battle - WADI AKARIT, North Africa WW2.

Veteran accounts of the key battle which led to victory in North Africa, Second World War

Wadi Akarit - World War Two's own Charge of the Light Brigade!

"A patrol went out that night. Lance Corporal Joe Ryder of Spennymoor went with them. He was a long-term member of 2 Platoon and told us afterwards how they had penetrated the enemy positions and, encountering an enemy patrol, had lain doggo. A member of the enemy patrol had put a foot on Joe's hand as he lay there ..."

Brian Moss, Sergeant, 233 Field Company, Royal Engineers

More great unpublished history, Second World War.

Feedback/reviews in Apple Podcasts - Thank you.

Military history, WW2

Interested in Bill Cheall's book? Link here for more information.

Fighting Through from Dunkirk to Hamburg, hardback, paperback and Kindle etc.

Three veterans' accounts of one battle - WADI AKARIT, North Africa WW2.

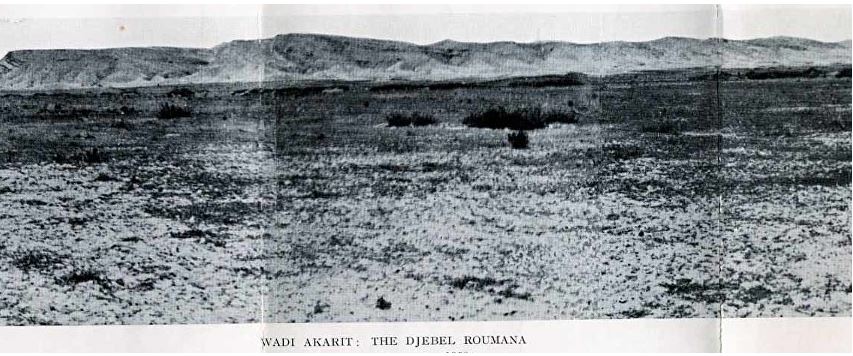

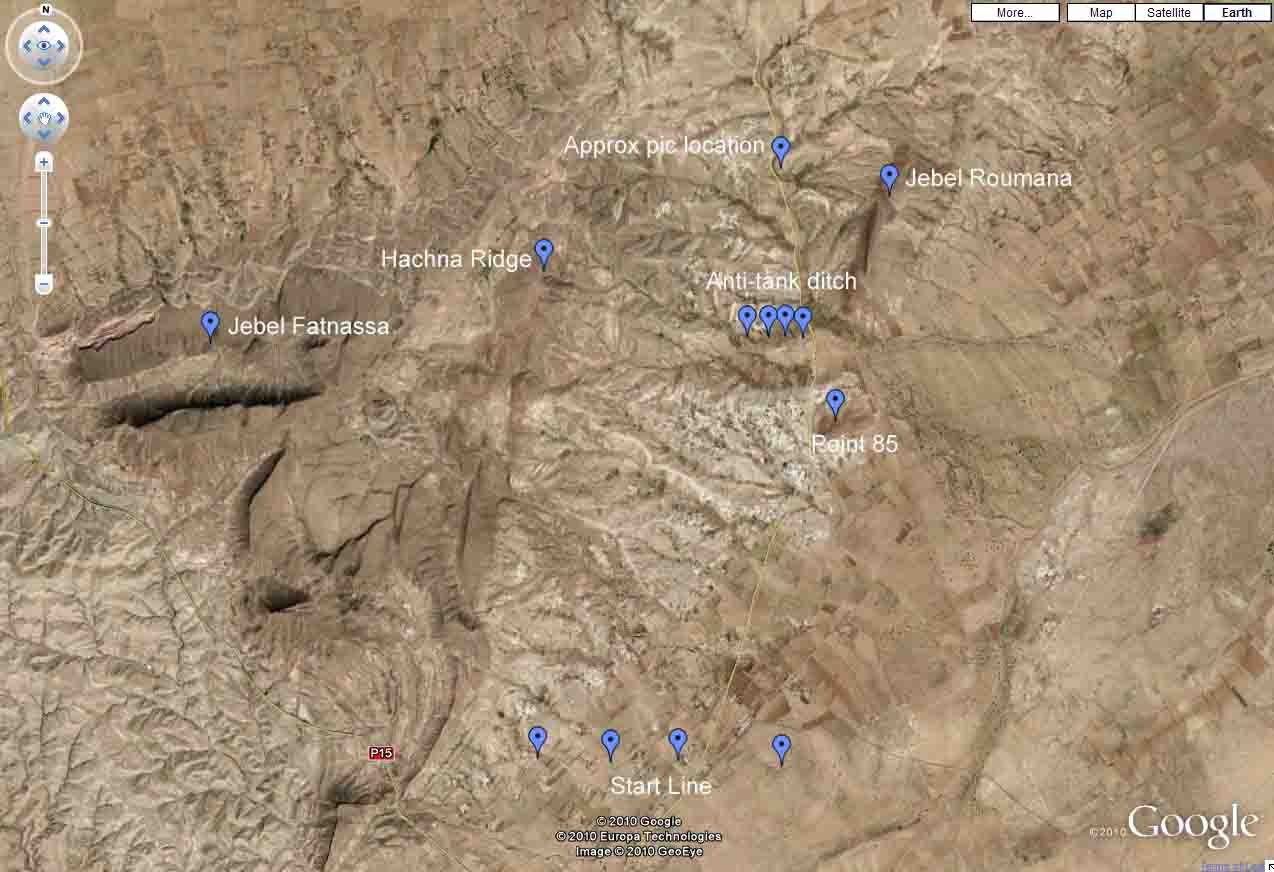

The plain at Wadi Akarit Tunisia North Africa 1943:

"A patrol went out that night. L/Cpl. Joe Ryder of Spennymoor went with them. He was a long-term member of 2 Platoon and told us afterwards how they had penetrated the enemy positions and, encountering an enemy patrol, had lain doggo. A member of the enemy patrol had put a foot on Joe's hand as he lay there ..." Sgt Brian Moss, 233 Field Company, Royal Engineers, pic below."

Episode 2 - Fighting Through Podcast - The Battle of the Wadi Akarit, 1943

This podcast episode includes the role of the Indian army and Ghurkas in WW2/WWII

I’m Paul Cheall, son of Bill Cheall whose WW2 memoirs have been published in hardback by pen and Sword – in FTFDTH, available from Pen and Sword direct or from Amazon and all good bookshops.

With the 70th anniversary of the battle of Wadi Akarit, Tunisia, on 6 April 2013, I am really pleased to depict the dramatic story which unfolded on this battlefield to bring Allied victory.

Wadi Akarit was surely World War Two's own Charge of the Light Brigade, except on this occasion the goodies won. But curiously a 'forgotten' battle. Yet it was the conflict which chased the Axis forces out of Africa. That day’s action cost the Eighth Army six-hundred dead, and three times that were maimed or wounded

I've been lucky to have access to dramatic unpublished veteran's accounts of this battle and you’ll hear them in this podcast.

There’s a detailed account from Sergeant Brian Moss, who bravely filled in a crucial anti-tank ditch which barred the Allied troops access to the hills where they would attack the enemy.

Brian's memoir is accompanied by a gripping passage from Bill Cheall's memoir and there’s also veteran Wilf Shaw's account of part of the battle.

So we have three soldiers' memories coming together 70 years later which together make really fascinating reading about the second world war.

Here’s a backdrop to the battle …

The Allies needed to be in command of North Africa in order to exercise control of the Mediterranean and simultaneously pose a threat to Italy and southern France. Following victory at Alamein, the soldiers of the British 8th Army progressed towards Tunisia, with a view to pushing the axis forces back North.

The enemy, led by Rommel, was making a stand amongst some hills near Wadi Akarit, a dried up river bed. They ‘had to be sent packing’, to use General Montgomery's words.

This was a savage, bloody battle and Bill Cheall was in the thick of it, losing several close comrades in tragic circumstances. It was also the battle in which Norfolk’s own VC, Colonel Seagrim, lost his life.

The enemy were holed up in some hills with very strong defences, including an anti-tank ditch the allies had to cross to even get to most of the enemy. But even to get there they had to cross a flat open plain for several thousand yards, taking Point 85, a small hill also known as the pimple in the process.

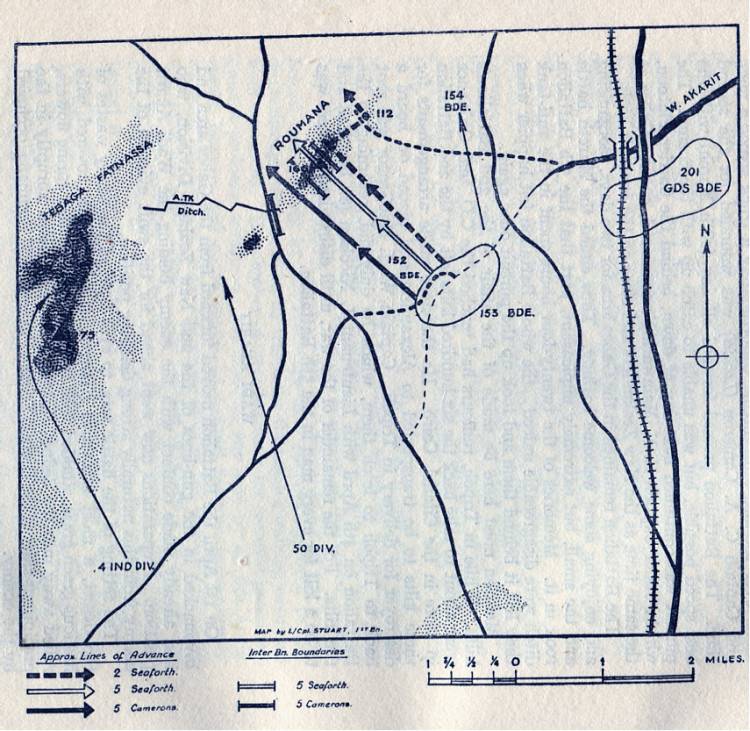

The battle involved the 4th Indian Div, 50 Div and 51 Highland Div amongst many others and started just before dawn.

I’m going to start with Bill Cheall’s memoir of the battle. He was with C company the 6 GH with 50 Div, also comprising 7gh and 5ey. WWII History podcast.

The following is just a short passage from Bill’s war diary about this battle. It is 6 April 1943 - The allies are attacking an enemy holed up in some hills in Tunisia ...

We were taken to a clearing about three miles away, which was screened from the enemy by trees. We were assembled and told in great detail and in no uncertain terms what was expected of us; also the method to be used to dislodge the enemy. This was so different to the attitude of our commanders previously, when we faced the enemy without any knowledge of the part we had to play. Unlike years ago, we were treated not as a number, but as a human being, by our officers and the lads responded accordingly by showing more interest than had previously been the case, simply because we had been put in the picture. Our officers, too, showed greater enthusiasm for the conflict knowing that they had the confidence of those who were behind them in what was to be done.

The enemy were ensconced in hills in the distance, only four miles away, and the plan of attack was as follows. The enemy held a good, strong position overlooking our every move on the perfectly flat plain over which we were to advance.

The hills were rather steep at the front, but our battalion was to attack a section just right of centre where the ground was level. Running through the valley was Wadi Akarit, an old dried-up riverbed. Running along the length of the front of the lower ground was an anti-tank ditch about six feet deep and eight feet wide, the whole area being mined and barbed-wired. We were given all the necessary information relating to the attack and with strict instructions to, ‘Give the buggers hell’.

The attack was to go in as follows: the 51st Highland Division on the right, the 4th Indian Ghurka Division on the left; our 69th Brigade would attack the centre gap, the 5th East Yorks on the left, the 7th Green Howards in the centre, and the 6th Green Howards on the right, but owing to the narrowness of the gap, the 6th would be in front of the 7th and would assault a prominent feature known as point 85, then we would spread out and let the 7th in.

We crossed the start line at 0400 hrs on a lovely moonlit night. It was almost eerie; everything was so quiet at this early hour and then, all of a sudden, as if somebody had pressed a switch, everything came to life as our twenty-five pounders opened up and we moved forward at a steady walking pace. We were led by our officers onto the flat plain, devoid of trees, and kept a distance of four or five yards apart. Advancing at a steady walking pace towards our objective, we had gone about one mile when the enemy let us know that he was expecting us and was responding accordingly. Shells began to fall a little way in front of us, then behind us and amongst us. He had found the range with the result that some of our lads began to fall, wounded, killed, at times blown to smithereens.

The enemy now opened up with 88mm and the shells were soon bursting amongst us with more accuracy as we advanced about eight yards apart, with our rifles across our chests. The enemy threw everything at us and we felt very exposed on that flat plain - but there was no turning back. Hell, I felt vulnerable but never afraid - we had other things to think about! Strangely enough, at this stage, fear never entered our heads; the job had to be done and there was no turning back.

Two thousand yards from the gap there was not even the usual scrub to drop behind. The 69th Brigade soon ran into trouble. Our C Company made a very spirited attack on point 85 and took it with the loss of some good lads. The East Yorks and the 7th Battalion were pinned down by heavy machine gun fire. The 4th Indian and 51st Highland had been successful in their initial attacks and somewhat reduced the firing down onto us and we advanced cautiously.

As we got nearer to the enemy the fire from their machine guns, mortars and 88s slackened off because we were below their line of fire. By the time we had reached Point 85, the Ghurkas had already gone into action in the dead of night in their usual way, stealthily, without any artillery support whatsoever, their Kukries (a very sharp, curved, broad knife about eighteen inches long) demanding a heavy penalty. These very brave soldiers from Nepal must have put the fear of death into the enemy. On the other hand, the enemy would not live long enough to be afraid, because in seconds his decapitated head would be on the ground.

Also during the dark hours, under cover of our twenty-five pounders, one tank had reached the anti-tank ditch. This tank had been knocked out and was still on top of the filled-in ditch and a very gory sight confronted us. The tank commander had been killed, I would say, by machine gun fire. His body, or what remained of it, was hanging over the edge of the turret. It had almost been cut in two - his head and shoulders were intact, but the whole middle of his body was splattered over the side - the intestines hanging out where the stomach had been ripped open and blood flowed freely everywhere. The commander must have been standing in the hatch observing when the tank was hit - what an awful sight - how cheap life was. Many of our young lads had not been in action before and this was the sight which greeted them.

We were now attacking as platoons and sections, and our section, led by Lance Corporal Coughlan, bending low to the ground, moved to the right and we had to tread warily because we were very often overlooked. We must have advanced about two hundred yards, not realizing that we were being observed from a concealed trench. All of a sudden, machine gun fire came from our right and Coughlan, who was next to me on my right, dropped dead - in an instant. It was an awful experience seeing poor Coughlan's life being ended so suddenly.

For a moment, we could not believe it, then my rage was up and I, being the senior soldier, took command. It all happened in seconds and I shouted to the other lads to keep firing towards the enemy trench on the hillside to make them keep their heads down.

Angry, I grabbed poor Coughlan's sub-machine gun and shouted, ‘Come on lads, charge the bastards, send them to hell, but keep firing and don't forget your grenades.’ Firing as I was running, I killed the first Italian who showed his head. When we were about ten yards away we had reached the top of the slit trench and we killed the survivors, five of them cowering in the bottom of the trench. WW2 podcast contd

It was no time for pussy footing; we were consumed with rage and had to kill them to pay for our fallen pal. We were so intoxicated; we could not hold back, as given the chance they would have killed us. This much I had learned at Dunkirk - no quarter given - and those Italians paid the supreme penalty. It was almost impossible to believe that a healthy young man's life could be ended in a split second. Only a few minutes before, I was talking to Coughlan - now he was dead. That event is still imprinted in my thoughts as if it were yesterday.

It took another four hours of killing and winkling out the enemy from his trenches and filthy dugouts in the hillsides before the firing quietened down, then stopped.

Years later, I discovered that the Green Howards and East Yorkshires had killed or captured practically the whole of the Italian Spezia Division.

We now rested, guards posted forward, and it was soon dark. Then we slept where we were, on the ground, our heads on our packs. This sad day was over and it was said that the battle of Wadi Akarit was one of the most successful fought by the Eighth Army. Our company commander won the MC.

Bill Cheall

6th Green Howards

1994

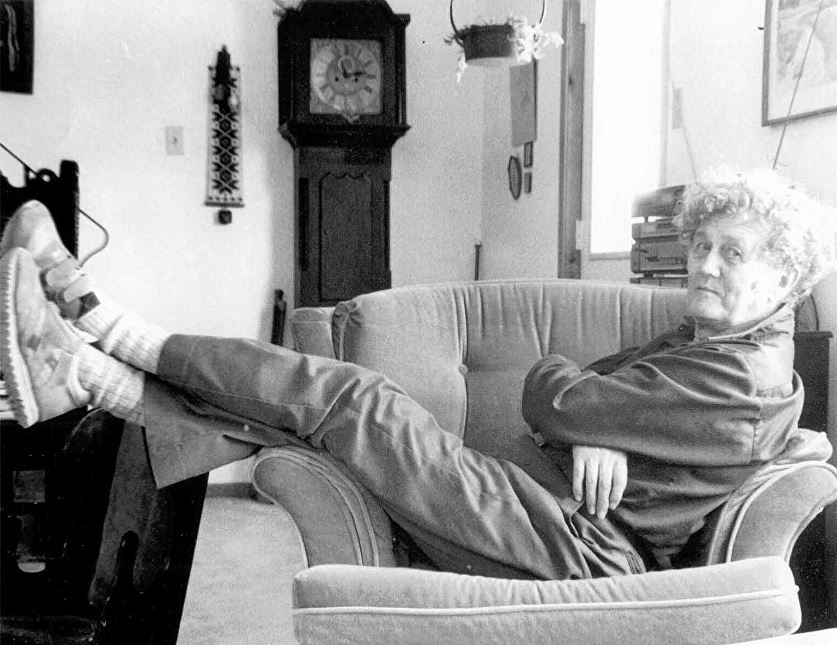

Wadi Akarit story by Brian Moss

Brian Moss - Sapper

233 Field Company, Royal Engineers

Brian Moss died in 1999 but not before he wrote his entire war memoir which covered a great deal of action including D-Day. This extract was kindly provided by his son Mike Moss, who lives in Canada.

After dark, we moved forward on foot, into our positions. I found myself a really good slit trench dug by unknown hands. I threw a few rocks in first to see if it was booby-trapped. It didn't explode so I threw down my bedroll and other gear. This was probably the best slit trench I ever had, deep and comfortable.

We awoke at dawn and studied our surroundings. The hills before us seemed nearer now. To give an idea of their height one of the foremost hills that we were to attack was known as Point 85 - because the summit was 85 meters above sea level. There was no sign of the enemy but we knew he must be there, looking down at us.

A patrol went out that night. L/Cpl. Joe Ryder of Spennymoor went with them. He was a long-term member of 2 Platoon and told us afterwards how they had penetrated the enemy positions and, encountering an enemy patrol, had lain doggo. A member of the enemy patrol had put a foot on Joe's hand as he lay there. Both men knew that if either of them raised the alarm they would be dead, so they ignored one another, and the moment passed.

Anticipating our next move, I exercised the men on blowing an anti-tank ditch. This was a drill that we had perfected at Mareth. Italian-dug anti-tank ditches were formidable affairs. Twelve or fifteen feet deep with the enemy side almost vertical, they were quite impassable to any tank. Even infantry found them difficult to cross without the use of scaling ladders.

Our drill included digging out holes on the enemy side and inserting tins of ammonal (ammonium nitrate mixed with aluminium powder). On exploding, this would ‘crack off’ an enormous triangular chunk of earth, which would drop into the ditch and fill it.

We were officially informed that day that we were to be involved in a set piece attack, and that one of our tasks would be the anti-tank ditch. On the afternoon of 5th April we were told to roll up our beds and other gear and leave them in our trenches. We were to parade in battle order after the evening meal.

At dusk, we climbed aboard our truck and jolted slowly away to BHQ the 7th Green Howards. What were we doing at 7GH, I wondered; 2 Platoon supported 5 EY! There, we stood in a line where, once again, a tablespoonful of over-proof rum was poured down our throats. What this was for, we couldn’t imagine, since we were not supposed to be going in until 4:30 am. Still, no-one refused the tot that CSM Nobes poured into us...

We were told to get some sleep. This we did by lying on the bare earth surrounded by infantry who were also attempting to sleep. Their carrier was nearby and was loaded to the brim with ammo, water and mortar bombs. I recall that night as extremely noisy.

The Luftwaffe seemed to know that we were not in slit trenches and they droned back and forth all night long, dropping case after case of butterfly bombs which thunderously exploded in carpets, unrolling across the ground at 200 mph. Luckily, they did not come nearer to us than about one hundred yards. The NZ ack-ack went crazy and none of us could sleep at that time. Eventually, the Luftwaffe departed to their sauerkraut, or whatever, and we slept. WW2 podcast contd

Later, a carrier engine burst into life. The vehicle moved and we heard an abbreviated scream. Apparently it had run over some poor devil asleep on the ground. We got to our feet, each thinking, that is not going to happen to me. We then received detailed orders.

Sgt. Betts, four sappers and I were to accompany the assaulting Company of 7GH. I never did know what Lt. Dudley and the rest of the platoon did. The selection of our little party seemed odd to me. I was to carry a section of Bangalore Torpedo while the others carried wire cutters. Obviously, we were expecting to encounter wire.

We were given to understand that the task of our assaulting Company was to secure the foremost defensive work, i.e., Point 85. The remainder of 7GH would then follow us in. We formed up and moved off. I marched alongside a Sgt. from 7GH, who was carrying a shovel over his shoulder. He explained, “The shovel blade protects my head, you see.”

In front, a Howard officer was checking the distance marched and direction by compass. After having gone about two miles we were halted and told to lie flat. Within a minute, the NZ guns turned night into day and thousands of shells tore overhead and exploded all over Point 85 in little red flashes. This continued for perhaps two minutes, and then the shelling suddenly stopped. We sprung to our feet and ran like madmen for Point 85, which was now illuminated again by gun flashes as the NZ guns fired at different targets.

I do not recall much in the way of defensive fire from Point 85 but there must have been some. In no time at all, we were at the base of the hill and a platoon dashed up the slope with fixed bayonets. We were instructed to go with the remainder of the Company around the hill to the left and I wondered why we were doing this if our task was to get the ‘Pimple.’ At that moment, I was appalled to see that dawn light was flooding the scene. If only we had started just ten minutes earlier!

We left the sounds of battle behind us as we raced on into what appeared to be a smallish hollow used for the growing of barley. The crop was sparse and only two feet high. It was then that we saw that we were surrounded on three sides by enemy positions, some no more than 150 yards away!

We could even see the heads of the enemy in their trenches. They were evidently too astonished to fire at the sight of so many men putting themselves right in front of their sights, like targets in a shooting gallery.

Up on Point 85, the 2nd Cheshires, our machine gun battalion, had by now set up their Vickers and they let fly. It was the signal for every Spandau, Fiat and Breda to open up on us. Bullets cracked only inches above our heads and I saw the barley heads chopped off and falling, so close were the bullets. But the enemy was firing downhill and they had the usual problem of firing too high. Twice, I saw our leading infantry attempt to get forward and twice they were cut down before they moved even ten yards. I was lying directly behind Dick Betts. I placed my head right up against the soles of his size 11 boots for protection. WWII podcast contd

“Hey, Dick!” I called. He turned and grinned. “If we get out of this one,” I said, “I’ll buy you dinner at the Brasserie Kalotyphos!” This was a reference to a meal we had shared at a place in Alex. Dick grinned again and nodded. At that moment, the enemy started to fire small mountain guns at us. With these they could hit us over open sights and nasty explosions were now throwing bits of bodies into the air. There was no future in this at all.

I felt a blow on my right buttock, followed by a sticky, spreading wetness. Putting down my hand, I was surprised to find not blood as I had expected, but lemon juice from my water bottle, which had been punctured by a bullet. This was the lemon juice I had found in the blockhouse at Piste Djorf, back at Mareth!

In my trouser pocket that morning was the small Molesworth Pocket Engineering Yearbook that Jack Gibson had sent me at Christmas. The pages became stained with the lemon juice, stains that are still evident more than fifty years later.

As far as I am aware, no order was ever given to retire but men in front were suddenly on their feet and running. Running back. Dick was on his feet. Then I was running too, as were our four sappers. We tore out of there at the double. How we avoided being hit, I will never know. But we all made it. We sprinted back to Point 85 at breakneck speed and ran around to the rear where we collapsed on the ground, panting like dogs, together with those infantry who managed to get out. Casualties had been very heavy. Nevertheless, we had achieved our primary objective. Point 85 was firmly in our hands. As we got our breath back, we were privileged to see a sight usually reserved only for the King's enemies.

There, only a hundred yards away, a British battalion was advancing straight towards us into the attack. It was the remainder of 7GH. Led by Colonel Seagrim who was waving a walking stick, their quick march changed to a jogtrot as they swept past us into the deadly hollow from which we had just been ejected. World War 2.

7GH were to have a hard time in that place. Pinned down for hours, they would eventually lose Seagrim; he would be killed before he could know of the V.C. he had won at the Bastion.

Since there was nothing for us to do, Dick decided to take us back to our lines. Most of us could do with a meal. Drained of our nervous juices, we stumbled back like zombies and took very little notice of the fixed line machine gunfire coming over our heads. At the cook's truck, we grabbed a mug of tea and then dropped into our slit trenches and were asleep in seconds.

At 11 am I was rudely awakened. Dudley stood over my slit trench grinning down at me.

“Come on, Sgt. Moss,” he said, “you’ve got to blow the anti-tank ditch!”

Oh, yes, the ditch. I scrambled out, wondering why he said “you” have got to blow the ditch and not “we.” I could have done with another six hours sleep but there was no time for that now. Dudley had already assembled fifteen men, a white armoured scout car and a 3-tonner. The truck carried tools and explosives as well as men. We all climbed aboard and Dudley led the way in a Jeep.

I suppose our destination would be about a mile to the left of Point 85, an area of peculiar circular lumps about one hundred feet in diameter and fifteen feet high sticking up here and there above general ground level.

We parked the transport in the lee of one of these lumps since the area was under shellfire. Dudley suggested that five men be left behind until I was ready and then they could bring up the explosive, which was in heavy crates. The remainder of us proceeded on foot directly towards the hills, carrying picks and shovels.

I think the shelling was 15-cm stuff. They came in screaming and exploded on the iron hard ground, throwing splinters hundreds of yards. We progressed therefore in a pattern of diving, crawling and scrambling. We were just the quick and the dead. If you weren’t quick, you were dead.

There was also a new noise in the sky, a pumping, howling wail, accompanied by wobbling smoke trails in the sky racing towards us and terminating in horrendous explosions. This was the first time I saw Nebelwerfers in action. I was impressed. Still, since I was drained of nervous energy by the affair at dawn, I felt no fear at all and I examined the torn off rocket tubes of the Nebelwerfers with interest.

It was evident that 5EY had been hard hit here. Torn and dismembered bodies lay everywhere. Most wore Balaclava helmets. It was later said that their leading companies suffered 70% casualties here.

I was leading ten men up into the shellfire. Then we saw enemy bunkers to the left and to the right. At fifty yards we saw weapons pointing at us, but we thought they were unmanned. I steered a course through these bunkers that I thought a tank could follow. After going for another sixty yards, there was the ditch! It was the usual kind of Italian ditch, the kind I had once spent the night in elsewhere.

5EY had cut step holes in the sides to enable men to climb them. I looked around for the best place to blow it.

Although I did not know it at the time, 5EY were only just in front of us, held up by heavy fire. The fire to which we were subjected was aimed at 5EY.

I settled on a good place and decided to take out a shovel-width trench, ten feet back from the edge of the ditch on the enemy side. I set the lads digging with the picks and shovels that they had carried up there, and you should have seen them go at it. Their picks whirled and thudded, and their shovels hurled out the earth in fine style.

To the rear, I could see tiny figures back there, struggling up through shell bursts with heavy crates. I waved so that they could see where we were. The work was going well so I detached three men to help move up the explosives. We finished the trench to a depth of three feet and a length of eight yards, and we prepared everything for the explosives. A shell burst suddenly obscured two carriers and we were sure they must have been killed. But, when the smoke cleared, they were still struggling towards us.

We tore open the crates as they arrived, wrenching out the black tins of ammonal. Recalling an instructor's words, I laughed like a maniac and yelled, “Ammonal must not come into contact with naked steel!” as I ripped off the circular tin lids with a bayonet.

We placed the opened tins in the trench. I knotted primers onto lengths of primacord, burying a primer in the contents of each tin. I then taped each length of primacord to a main of the same material, arranging for the separate lengths to enter the main at a sweet curve, which the detonating wave could safely follow. A detonator and two minutes of safety fuse completed my arrangements. The lads had been backfilling the trench while I worked.

It was now time to blow the ditch. I sent all men into cover in the enemy bunkers. Then I did something that even now makes me laugh. I took out my whistle and blew a long blast signifying an imminent explosion. In view of what was dropping all around us, this was ludicrous and would not be heard anyway! WWII podcast contd

I placed a match head on the obliquely cut safety fuse. You always cut the fuse on the slant. I stroked the matchbox across the match head and the fuse started to burn! Then I too, found a bunker.

In due course, there was an earth shock and a rumble. Stones fell all around. Then I peeped out. The blast had been remarkably successful. The sharp deep vee had gone! The ditch was more than three quarters filled, and the lip of the enemy side had disappeared!

It was time for the “bent shovels.” The bent shovel was a long handled Egyptian shovel, the steel neck of which had been heated and bent so that the blade was at right angles to the shaft. Each man had carried one of these as well as a pick or GS shovel and his rifle.

My lads were emerging from the bunkers and, to my surprise, a dozen enemy infantry came out first, their hands in the air. They were Italians of the Spezia Division. The troops holding 5EY were 90 Light and 15 Panzer.

I detailed one man to guard the prisoners and the rest of us went like hell at the crossing with the bent shovels. With this kind of shovel, you drag loosened earth towards you. We dragged fill down towards the middle of the ditch, and, within five minutes, had shaped it into a gentle curve.

“Damned good job!” said Wally Douglas. I agreed with him.

Someone yelled and we looked back. Five hundred yards behind us, an endless stream of Shermans was approaching. The small figure directing them towards us was undoubtedly Lt. Dudley. These tanks were 10 Corps.

The Shermans were painted a colour that was almost white. We stood there watching the approaching tanks and making last minute adjustments to our work. The first tank arrived, hesitated, and then lurched down onto the crossing and roared triumphantly up onto the other side. The crossing worked! I indicated to the driver the way forward and off it went. 5EY would soon be much happier. A second tank crossed, then a third. The crossing was improving with every tank that went over. The edges were being crumbled off and the whole affair was looking better by the minute.

At the time, I assumed that 10 Corps crossed the ditch at several places. Many years later, I read that they crossed in only one place so I came to understand how important my crossing had been. This was possibly the most important thing I ever did during the war.

Brian Moss

233 Field Company, Royal Engineers

Wilf Shaw

I was back In the Signal Platoon now. I was co-signaller with Bill Wright, one of the original crowd way back at Aske Hall in 1940. The battle here was the by now familiar heavy artillery barrage against dug in positions situated on the high ground across our front. Unlike Alamein, the attack took place in daylight. Ginger, (Bill Wright's nickname) and myself were attached to B Coy, one carrying the 18 set, and the other the spare batteries, plus all the other equipment of course.

We started our ascent Into the hilly ground, through the white tapes laid down by the Engineers - suddenly we were under heavy fire. We got the order to deploy, we scattered widely, men went up on anti-personnel mines or hit with shell and mortar fire - Ginger and I dug in fast and lay praying and sweating it out but at least this time, unlike Alamein, I was in a position where I didn’t have to contend with deadly small arms fire. I dont recall exactly how long we were pinned down - it seemed chaos all around us, with cries of "Stretcher Bearer!" and everybody trying to shout out commands of one sort or another.

A Bren Carrier went up on a mine right beside where we were lay - the crew spewed out and tumbled to the ground in a daze. We could hear a lot of small arms and automatic fire from up front, then comparative silence. We got the order to move forward - we moved through a ravine between the hills, part of which was under fire from 88 millimeters. We came to a halt again, right next to slit trench which had been used by the Italians, a shell crashed down, not far away from us. We dived in the slit trench - the Italians had used it as a toilet and it stunk to high heaven. We moved on again - glad to get away from the 88's and the stink - we moved forward right through the hills and into the clear beyond. I couldn't understand what a new army boot was doing lying on the ground nearby - I picked it up, then dropped it immediately, the foot was still in it!

Wilf Shaw

Following is the content of a letter to Wilf, written by pal Fred Zilken about the battle and Jimmy's death:

"I was scared to death of being up front, but even more scared of running away. Another thing, Wilf - that Wadi Akarit 'do' in Tunisia - me and Jimmy Wilson were with D Coy as we advanced against those Italian positions - Jim was carrying the 18 set, I was operating and carrying the batteries - as we advanced across the open ground - shells and mortar shells were dropping around like rain - I said to Jim, 'Lets make a run for it - get into a slit trench' but then a mortar bomb shell landed - must have been at our feet!! A deafening explosion - and I felt a sharp pain in my top right hand thigh, and at the same time, I saw Jimmy riddled with shrapnel crumple to the floor. I could do nothing for him.

I have often thought - why did I only get one piece and Jimmy got death? There was just 2 feet between us - Jimmy had lengthened the lead between the 18 set and batteries, just a couple of days before, whilst we were still moving up. I can’t understand how Jimmy was killed and I got away with just one piece of shrapnel - it's still in my back, I didn’t know until I went for an X Ray for an appendix operation!"

Wilf said, "Jim Wilson was such a lovely lad - so inoffensive, but fully committed to the job he had to do.

Wilf Postcript about the battle of Wadi Akarit

In the battle for Mareth and Wadi Akarit alone, the 6th and 7th Green Howards had 500 casualties. As an advancing force, these would be either killed or wounded. The Signal Officer, Capt Levins, was himself one of the wounded - there were others in the Signal Platoon that at the time I knew well but whose names now I have forgotten.

I don’t have to tax my memory about any of those awful times, they are engraved all too indelibly in my mind - this time, I wasn't one of the casualties - I was one of the survivors, but my nerves were near to breaking point.

Akarit was almost the end of the campaign in North Africa. The last encounter with the Afrika Corps as far as we were concerned took place at Enfidaville, just a few weeks later when we were stuck for days on end in a kind of large orchard, which was infested with the largest and most voracious mosquitoes we had ever seen - they just never stopped biting us. Fortunately for us, they were non malarial.

I find it hard to believe I climbed that Wadi Akarit now - what a desolate God-forsaken place it is.

Wilf Shaw,

6th Battalion, Green Howards

Featured Episodes

If you're going to binge, best start at No 1, Dunkirk, the most popular episode of all. Welcome! Paul.

PS. Just swipe left to browse if you're on mobile.