43 Canadian Seaman Ray Fitchett POW and HMS Exeter - spoken memoir

POW in Japan, WWII

HMS Exeter was sunk in Pacific waters during the second world war. Ray Fitchett made a recording of his tale of survival in Japan – abandoning ship in shark infested waters followed by three years’ captivity as a POW.

Hear the terrifying tale of how he survived.

"They decided to put some of us down the coal mine but I didn't fancy that. So I went to the tail end of the queue of guys and I thought I'd get a job at the top of the mine."

"If you got lucky you might pick up some orange peel - You couldn’t eat the whole lot but you could scrape the white part out and that was luxury."

More great unpublished history - of the Second World War.

Normandy Memorial Trust Appeal - 75 veteran D-Day stories

Link to feedback/reviews at Apple Podcasts - Thank you.

Ray Fitchett proudly wearing his new smart uniform with an HMS Raleigh hat

POW Navy second world war WW2 podcast ;)

Interested in Bill Cheall's book? Link here for more information.

Fighting Through from Dunkirk to Hamburg, hardback, paperback and Kindle etc.

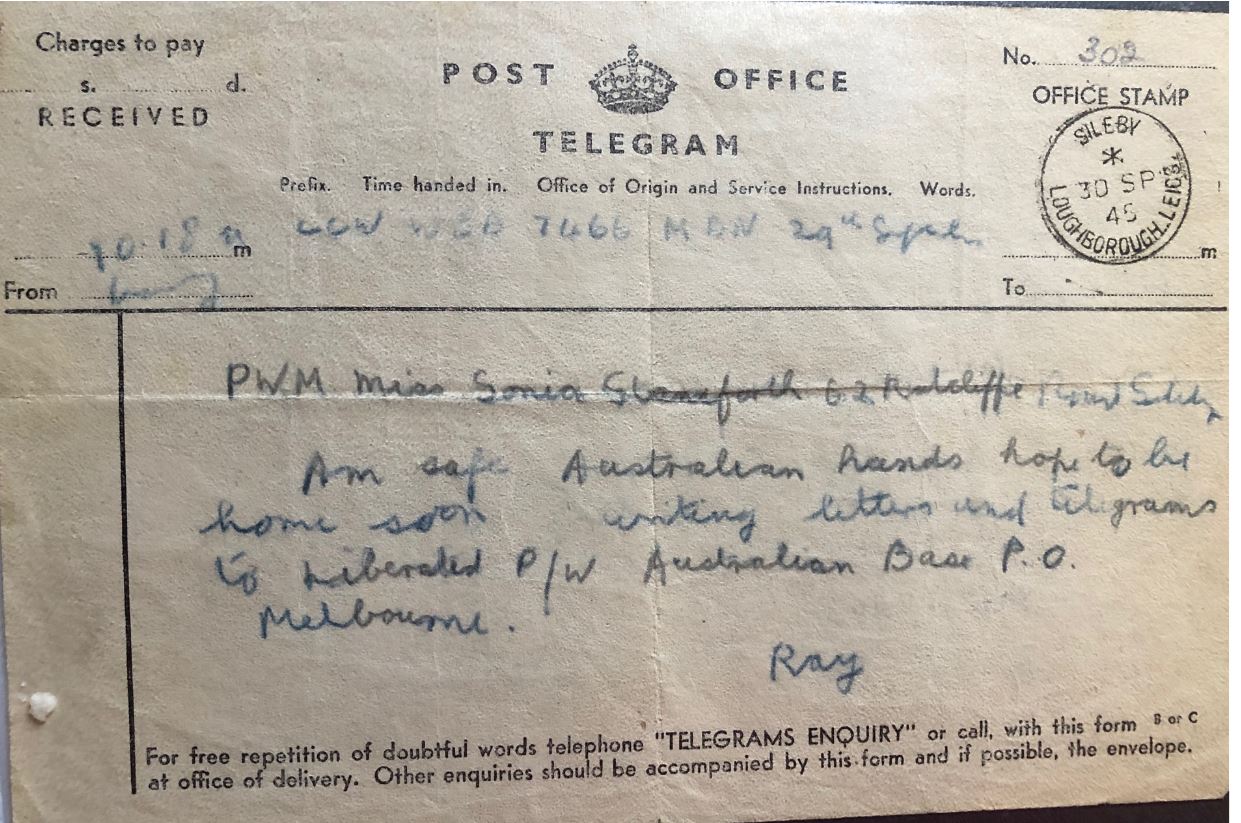

Ray's Telegram home in the second world war

Ray and comrades in uniform world war two podcast. Back 4th from left

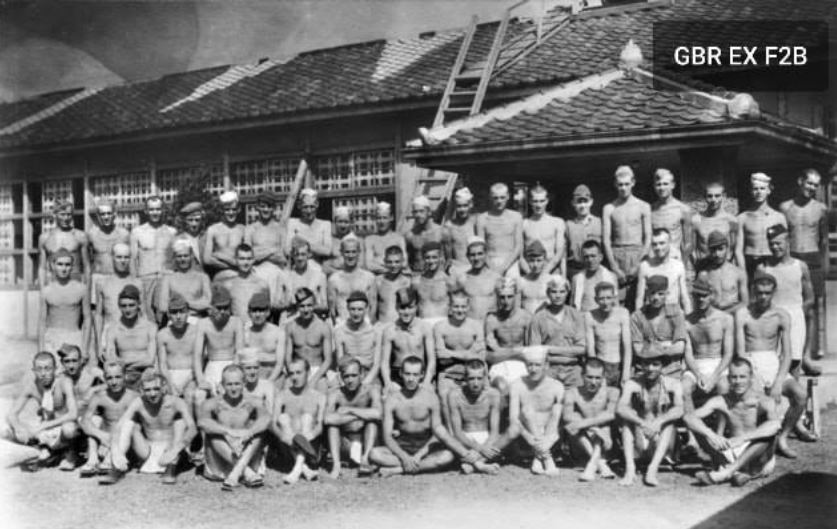

Ray as POW - second row, 8th person from the right, at Nagasaki Fukuoka - 2B camp

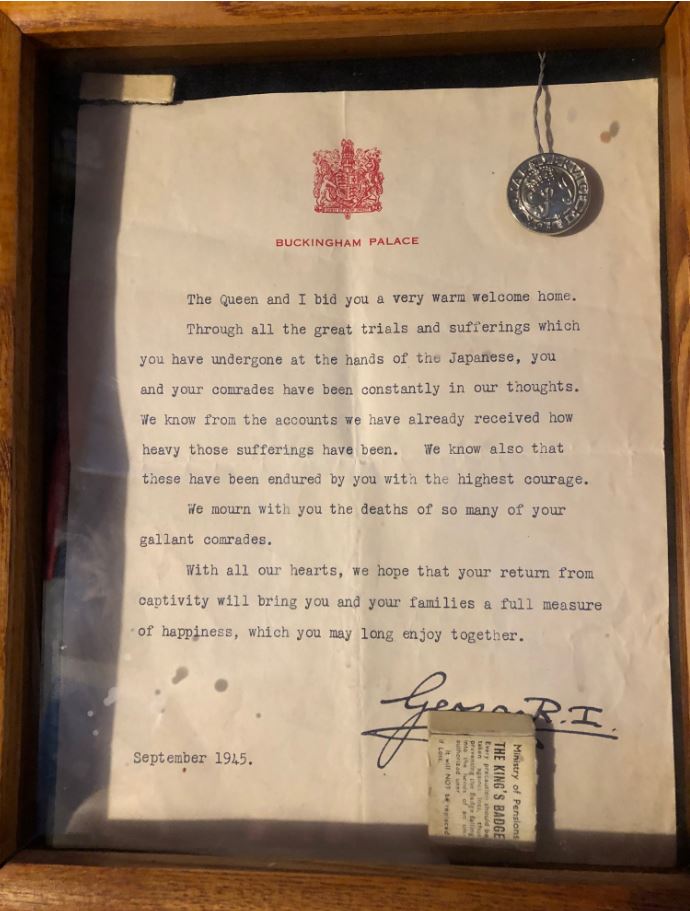

Letter to Ray Fitchett from King George VI

Arial view of the POW camp WW2

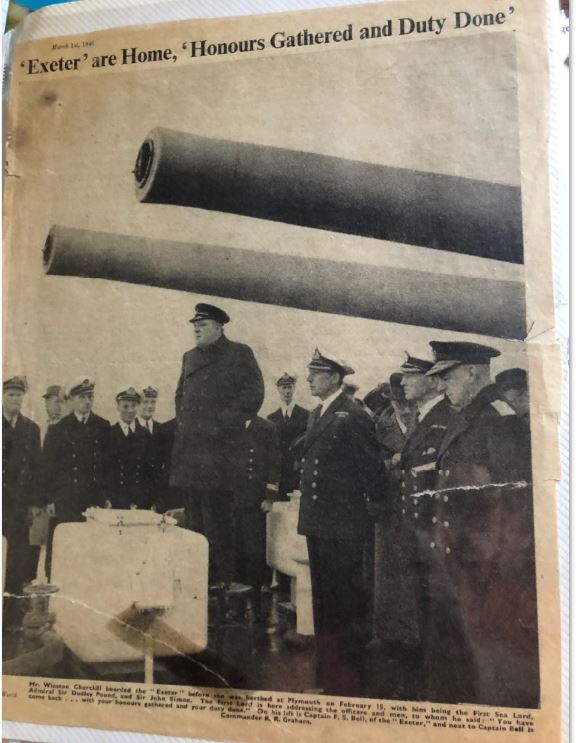

The homecoming

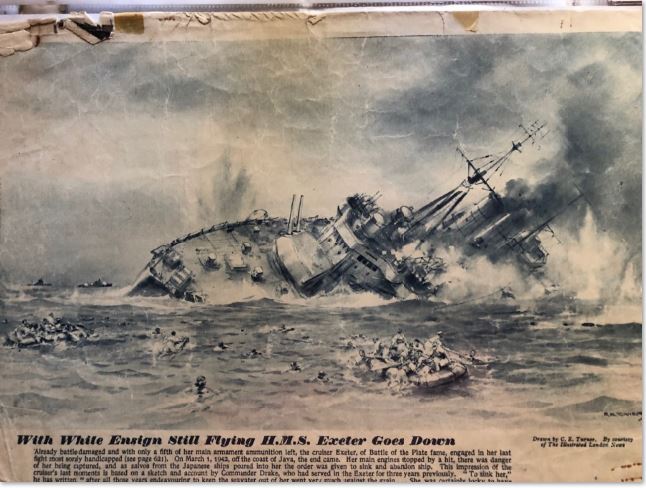

HMS Exeter goes down

News cutting

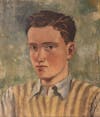

Albert Kelly HMS Exeter WW2 podcast history

Fighting Through Podcast - Episode 43 – POW, Canadian Able Seaman Ray Fitchett HMS Exeter, WW2

and news of the new British Normandy Memorial in France.

…

That recording was produced by the British Normandy Memorial Trust. It’s actually the audio background to one of 75 videos that the trust is producing to commemorate the 75th anniversary of D-Day, which is on 6 June 2019.

I was honoured to be asked by them to record a tribute to our very own Lance Sergeant Rufty Hill, who’s full heroic story is covered in episode 25. His is just one of the many stories of people who died for our many freedoms today.

The British Normandy Memorial (to world war two) will stand in a place where history was shaped. From its elevated hillside position, visitors will have a clear view of one of the beaches where British forces landed on D-Day. On the columns of the Memorial will be the names of more than twenty two thousand men and women.

The overwhelming majority of the names will be those of the British soldiers, sailors, marines and airmen who lost their lives on D-Day or in the weeks that followed as the Allies fought their way through Normandy.

But there will also be the names of men and women from other nations who fought under British command, from Ireland and European nations like France, the Netherlands and Poland which had been occupied by the Nazis.

Names of those from further afield who had enlisted in or been attached to the British armed forces from, among other countries, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa - and the United States of America - will also be listed on the memorial.

The losses of the British Merchant Navy will be remembered, as will civilian losses, most notably those suffered by France. They will have their own dedicated place of remembrance.

There’s a web site you can visit which hosts not only the 75 2 minute videos, but also gives a lot more background to the project and includes a digital brochure containing endorsements from several people including HRH The Prince of Wales. And the brochure contains a load of terrific photographs of D-Day action and more – it’s well worth a read. WWII.

And if you wish to make a donation to this very worthy cause, there’s an opportunity to do so.

I’m off to Normandy on a Green Howards trip in a couple of weeks and will most certainly make a beeline for this monument as it’s going to contains all those names I mentioned in the clip – Lance Sergeant Rufty Hill, Captain Linn and Captain Chambers and more. There’ll be no end of Dad’s fallen comrades listed and I hope I can do an episode on this specific topic sometime in the future. Right now I think it’s just a magnificent statue that’s gone up, and the site and monuments have yet to be developed.

There’s a link in the show notes to the Normandy Memorial Trust website – take a shufty and maybe help pay for a name to be engraved whilst you’re there.

We’ll move on now – you tuned in to hear about Ray Fitchett …

Music

Fighting Through Podcast - Episode 43 – Able Seaman Ray Fitchett HMS Exeter, Royal Navy

We started convoys to the Far East. We got tangled up with the Japanese fleet and got hit in the shell room with a Japanese shell.

The ship was listing over quite badly then with just a few officers left on board - they said ‘every man for himself, so over the side I went, and I didn’t think about it.

They decided to put some of us down the coal mine but I didn't fancy that. So I went to the tail end of the queue of guys and I thought I'd get a job at the top of the mine.

If you got lucky you might pick up some orange peel - You couldn’t eat the whole lot but you could scrape the white part out and that was luxury.

….

More great unpublished history of WWII and WW2

Hello again

I’m Paul Cheall, son of Bill Cheall whose WW2 memoirs have been published by Pen and Sword – in FTFDTH.

My dad fought at Dunkirk, North Africa Sicily D-day and Germany.

The aim of the Fighting Through Podcast is to give you the stories behind the story. You’ll hear memoirs and memories of veterans connected to Dad’s war in some way – and much more.

Today’s episode is about Able Seaman Ray Fitchett from Canada. His Royal Naval ship, HMS Exeter was sunk in Pacific waters during the second world war. Listener Cole Gill has sent me a gripping recording of his grandpa’s tale of survival in Japan – abandoning ship in shark infested waters followed by over three years’ captivity as a POW – so that’s RAY FITCHET, Royal Navy.

I’ve got a few more stories with HMS Exeter connections that listeners have sent in so I’m going to cover those first. Before that, here’s a quick summary of HMS Exeter’s background from good old Wikipedia.

HMS Exeter was a York-class heavy cruiser built for the British Royal Navy during the late 1920s. When World War II began in September 1939, she was assigned to patrol South American waters against German commerce raiders.

Exeter was one of three British cruisers that fought the German pocket battleship, the Admiral Graf Spee, in the Battle of the River Plate.

She was severely damaged during the battle, and she was in the shipyard for over a year.

After her repairs were completed, the ship spent most of 1941 on convoy escort duties before she was transferred to the Far East after the start of the Pacific War in December 41.

The Exeter was assigned to escorting convoys during the Malayan Campaign, and this continued in February 1942 as the Japanese prepared to invade the Dutch East Indies and she took on a more active defensive role.

She was in the Battle of the Java Sea later that month and was crippled early in the battle, so she did not play much of a role, as she withdrew.

Just two days later, she was sunk by Japanese ships in the Second Battle of the Java Sea.

Arthur Kelly

Another shipping story from Tom Lee about a poignant HMS Exeter and Dunkirk connection. There’s also a plea for knowledge of distant family coming out of this so if you’re in Canada and have Kelly in your family history, keep your ears peeled!

My father in law was Arthur Kelly, b 1919 in Everton. Liverpool, England.

His brothers were Albert and Joe and there was sister Emily Kelly.

Albert became a stoker on HMS Exeter and was killed at the battle of the River Plate by a shell from the Graf Spee.

Arthur was at Dunkirk but understandably never wanted to talk about it, until that is, shortly before his death when he told that by fate he had met up on the beaches with his lost brother Joe.

Arthur and Joe met up again at an army camp some months later, both not knowing if the other had made it back. This was Riddlesworth near Thetford in Norfolk, England.

The other brother, Arthur, had suffered traumas and emigrated to Canada after the war and lost touch with the family. My wife is sure there is a branch of her family in Canada about which she knows nothing!

Tom has sent me a photo of Arthur (always known as Titch, due to his diminutive size) in uniform from 1945.

As an aside, the father of the family, Robert Kelly, was invalided after WW1 and the family were very poor. As a result, son Arthur walked to London from Liverpool as a 14 year old to find work (initially as a bell boy at a London hotel).

He joined the army when he was under age (three square meals a day and a bed) but his mother found out and he was discharged. He joined again as soon as he was old enough and went to France with the BEF before coming back via Dunkirk (on, he believed, a steamer called Antwerp?).

He suffered with his lungs for the rest of his life, due to spending so long in the water awaiting rescue, but he never claimed a day's social security in his life maintaining that there was always work if you looked for it "it may be dirty, smelly or unpleasant, but there's always work".

As such he had many trades including; plumbing, milkman and allsorts

Tom Lee

Thanks Tom – curious overlaps there with so much else we’ve heard about in the FTP. Anyway, listener, if you’re a Canadian Kelly with an Arthur Kelly who was at Dunkirk – do please get in touch and tell us your war stories!

War Stuff

Alexa

This is great news for anyone listening to the FTP on your favourite voice assistant Axela, but who would prefer a man’s voice to introduce it. For those who don’t want Axela listening in on their conversations, apparently they are developing a male version which doesn’t listen to anything! They are calling it Alex! Boom boom!

Iain Mathie, From Edinburgh Scotland Email

My great uncle, George Grant Smith, served in the merchant navy during World War Two. He was in the Pacific and his ship was hit by a Japanese sub. He risked his life trying to save his captain but sadly he was dead by the time he got to him.

He suffered 60% burns to his body on the way out but lived a full life and sadly passed in the 90s. He has been given no thanks or anything for this and I'm trying to find out what ship he was on etc so I can try get some recognition for him. I'm just wondering if you had any tips on how to go about this.

Richard I know you’re currently scouting around relatives to find out what more details you can, and whether or not you get any more info I’d recommend you Google (what else?!) Ships Forums and you’ll find a load of discussion forums to choose from – there’s Ships Nostalgia, Shipping History, several others and you might find some help in those.

I suspect whatever happens you will get a lot of satisfaction from your research and can’t help thinking somewhere along the line you’ll be able to track down more details about George Grant Smith. It’s a good job his middle name is Grant mind you because no doubt it’ll help narrow down the options you’d otherwise be faced with!

Thanks for getting in touch with that great story of heroism and even if you don’t get a posthumous medal for George, I will here and now grant him the highly coveted FTP ‘How Good is That’ award for June 2019. Well done that man.

Interlude

You’re listening to the Fighting Through Podcast, Episode 43 Ray Fitchett and HMS Exeter – Great Unpublished History – World War II and more, WW2 and WWII

Ray Fitchett – original

Now Cole Gill kindly sent me a recording of his grandpa talking about his tale of the war in the Far East. How he abandoned ship in shark infested waters and then survived by five years in captivity as a POW.

Unfortunately the sound quality is very mixed and at times it’s difficult to hear what’s being said. However, despite the imperfections you can’t ignore how precious a piece of history this is!

As far as I’m concerned what you can hear more than makes up for what you can’t hear so I suggest we run with it as best we can.

And later on in the episode I am going to tell the story again, myself, from a transcript I’ve had typed. So if there’s stuff you don’t catch, you’ll get a second chance.

This is naval seaman RAY FITCHET.

Transition

Interlude

You’re listening to the Fighting Through Podcast, Episode 43 Ray Fitchett and HMS Exeter – Great Unpublished History – of the second world war and more

WW2 and WWII, World War II and more

Ray Fitchett – my transcription

This is Ray Fitchett, I am an ex naval man and I'm going to give you a taste of my lifetime.

My parents got married in 1912

Their name was Fitchett, same name as mine.

George Fitchett and Carmen Fitchett.

Carmen used to be a Richardson before she was married - yeah and I thought I would give you a bit of an idea what I've been up to these years.

We had eight children out here in Canada, my mother and parents did.

And so then things got tough and my mother's parents in England were getting old. My mother went with seven of us back to England. While we were in England things got bad and the land got all dried out and a lot of the farmers had to quit farming because it was so bad.

Later on the War broke out and there were four of us in our family ready for the services, so we all joined up and I joined the Navy, because my uncle was in the Navy in the last 1914-18 War. I served on the cruiser Exeter.

I got called up first didn’t I? I got called up when I was 22 after I’d volunteered so I could get in the Navy. I had one month training and after that I went home on two weeks' leave and then I was courting my girlfriend then, Sonya Staniforth. We decided to get engaged before I went away.

I went overseas, convoyed troops overseas to Africa and all around there, and different parts of the world. My girlfriend and wife we never saw one another for five years.

Listener it’s interesting that Ray could have transported Dad or any of his Green Howard comrades to or from Africa if that’s the route he was sailing.

In 1941 the Japanese came into the War and we eventually started convoys to the Dutch Indies, Java, Borneo, Burma and Singapore. We got tangled up with the Japanese fleet and got hit in the shell room with a Japanese shell.

We had to withdraw from there and went to Surabaya and took the dead off. And then the shells that they were using on us, we looked at the heads of one and it was made in England 1916 so they’d used them in the First World War!

They joined up and were fighting with us in that War so they had the ammunition from WW1 and pumped it back at us in WW2!.

I remember picking the head of it up because it had gone into the engine room and ripped it up. I remember picking it up and it said made in England 1916.

When we came out again the Japanese fleet was waiting for us. We eventually got hit in the engine room again and that put a stop to it - and we had to fight it out there until all the ammunition was gone.

We had to abandon ship, and jumped into the ocean.

When I jumped overboard most of my friends were already in the water but I was late getting off board. I was in a turret so I didn’t know it was abandon ship but eventually I jumped overboard, and at that time I had no life belt because I’d been in the turret.

The ship was listing over quite badly then with just a few officers left on board - and they’d said every man for himself, so over the side I went, and I didn’t think about it.

I had no life belt, but I saw a piece of wood about three foot square and another sailor was clinging on to it so I clinged along with him. Soon after that we saw on the horizon these Japanese ships coming up - I recognised the flag of the rising sun

I said to let go of the wood I'm not staying here it's a shark infested sea and we'll only get gobbled up by the sharks. I didn’t particularly want to [stay there] if there was any chance of living.

I wanted to live a bit longer but this coloured fella he said “No I'll leave you to it, I'm not going to be a prisoner and he just let go of the board that I was hanging on to and then off he went and left me to it, and I laid flat on this board. It was quite a thick board which had rope around it that you could cling onto, but most of the other guys jumped overboard and got onto boats and dinghies and that - most of them were machine gunned by the Japanese, and so I swam across and the Japanese threw me a rope to climb up to them.

I got half way up but wasn’t very good, and I slipped down again and had another go, and I slipped down again - and then he slapped his hand down and said to heck with you - die there.

But then eventually I got the rope again and just got the edge of the board to the ship - a destroyer - and then he pulled me in. And then he saw I’d got no jewellery or rings so he was a bit disappointed he hadn’t got anything, because they had to give up all their jewellery and gold during the War.

So then he hustled me onto the back of the stern of the ship, and there were a lot more of our guys there all badly burned out of the boiler room and all the skin was hanging off them, so I sat there with them and then we took off and we were a couple of days there on that destroyer and then eventually along came a big Red Cross liner.

It was a Dutch liner and was trying to get to Australia, that's what I understood, but the Japanese put a couple of shells across it and they stopped it, boarded it and took it over, and then they transferred us onto it.

We were taken to the prison camp in Java, Makassar - and they said they would allow the Red Cross people on the ship to make us a meal and they cooked us rice and prunes and stuff.

When we got to Makassar they said they were going to let us eat it, but they just chased us off the ship into Makassar and they never let us have the food after all.

World War Two Podcast

Then we had to run at the double all the way through the village, 100 degrees - and all the people took all our shoes and stuff off. They had never seen good shoes and stuff like that, and so we had to wrap our feet up with rag, but eventually that would all come off - and we had to run quite a way through Makassar to what was a Dutch army camp.

But then the Dutch were captured, so there was nobody in the camp - they had all fled up into the mountains but there were some Indonesian and Javanese there. Later on we got into camp, and it had polished wooden floors - a big marble place - nice place - but then you had to lie on the floor - but they took all the wooden floors and made us lay on the cement or marble.

It was full of mosquitos at that time. We had nine months in there making roads in the jungle and then they basically decided to ship some of us to Japan to work in Nagasaki.

I am going to tell you about the trip when we took off from Makassar to head for Japan where we were going to work in the dockyards. So on this boat - it was an old troop ship that some of the Japanese were going back to Japan on - they’d been fighting in Burma and Java there, and they were going back.

So they took the planks off the deck and they put us right down the bottom of the bilges, steel girders, with the freight of the ship. And down there they had cases and cases of all different animals and chickens and stuff that they’d taken from Java in the jungle like snakes and lizards and stuff.

And they were all in crates and they were all down [in] the bottom bilges and that's where they put all us guys. Then they put the planks on the top of the hole - with just one hole so some air could get down there, and then every now and again they would come down and take some of these chickens and feed them to the lizards.

The lizards only sucked the blood out of them, and after they had gone back up we would reach in these cages with all these lizards and snakes that were in. They only just sucked on the blood mostly so we were reaching in and we would pull these chickens out and we would eat them, mind they would be raw but it was better than being hungry.

So that was a trip - I can't remember how many days it took from Makassar to Japan. We had a big tidal wave, and like you get here like when you get a typhoon or a hurricane that comes out of the sea and it whips up on the ground.

It lifted the ship right up in the air and we thought we had been torpedoed and the ship rolled over on its side and rolled back - and all these crates of animals; it was dark and we were all yelling and shouting and the crates all fell down on top of us and we couldn’t see what we were doing. We just thought we had been torpedoed by the Japanese and I thought we have either been torpedoed by our own American ship or a submarine.

And then eventually [we realised] it was one of these big tidal waves - it had lifted the ship right up in the air like a whirlwind, like you get on the ground and then eventually it straightened up and we went on to Japan and into Fukuoka - that's just off Nagasaki but Fukuoka is just across on a ferry boat.

And the people from Nagasaki used to come across to this dockyard, it was the Mitsubishi dockyard in Fukuoka.

So we had to learn there how to build ships but we were pretty weak because we didn’t get much to eat, and when we first got taken they only gave us one bun between two so we weren’t too strong.

While we were in Java we never got a chance to have much clothing, so we were pretty black looking from the sun and working in the jungle for nine months with the sun near 100 degrees or more - so they gave us a coat and some trousers but no shoes, you had bare feet.

You made some wooden clogs for yourself, a piece of wood with a strap over, like most of the Japanese wear.

So when we got to Japan the ship docked at this dockyard and they said some had got to learn staging [Scaffolding], some on riveting and some on welding. It all had to be detailed, and we had to learn how to do it, and they made us do it, so they could [take their men off the work and send them into the fighting services].

So we worked in the dockyard – with Koreans … they were slave labour too, they had been fighting the Koreans for many years and they were fighting the Chinamen for many years too; the Chinese.

We learnt everything eventually. I learned something, I was a driller, and I had to ream the holes out for riveters to put the rivets in. And then the deck, it was a dry dock, and if you dropped down 100 feet, 60 feet, down there in the dry dock you are a dead duck. So it was a dangerous job and I [also] had to rig the scaffolding and stuff like that and that was a pretty dangerous job.

Sometimes they would give you a little jar of chilli pepper and they called it Tongarashi and you could sprinkle on banana skins - if you did you could use the white part of the banana skin.

Orange peel that was a luxury - if you got that, it was Japanese oranges. Any other food they wouldn’t allow you to eat it at all. We got pumpkin leaves and marrow leaves and all that kind of stuff. That’s poisonous but they allow you to boil it to boil the poison out before you eat them.

You just got rice in a kipper tin, just a bit of rice and you had to work in the dock yard all day, 12 hours on that stuff, so you were glad to come by anything.

Sometimes you'd go into the garbage cans and get the fish guts. Stomach of fish and bones and then you’d roast them in a tin on the rivet fire and dry them and sprinkle them on your rice.

They had lots of fish but they threw all the insides away and they’d normally give it to the pigs, but at night times if you had the job of feeding the pigs then you could pack [pinch] a lot of the fish stomachs and bones and stuff like that and you’d put it in tins and roast it on the fire and make bone meal out of it.

After a while they decided to detail some of us to go out and work in the fields setting [sowing] sweet potato and yams. And we had to work, me and my mate, and you would work like we did in the jungle and you had rows of hundreds. They would stand behind you and make sure you kept working.

We had to make a big road through the jungle in Java and we lost a lot of guys who died of malaria. Altogether I had seven bouts of malaria and each time I had diphtheria.

I never did get dysentery, I would eat a lot of burnt wood and charcoal which was very good for your stomach. But then things got tough. In Japan they decided to put some of us down the coal mine but I never did fancy going down the coal mine. My friend, a neighbour, who was in the First War once told me he had to work down the coal mines and he said it was terrible, and I didn’t fancy going down there.

So I went the tail end of the queue of guys and I thought I'd get a job at the top of the mine, but when it came to it I got the bottom of the mine and the ones that were on the front row they got the top of the mine.

Second World War Podcast

There were different shifts. This coal mine went under the sea and it was called the hot box. And the sea was still seeping through the stones and you had to go down there and drill in sixes and drill and blast and fill these big wagons. There were loads of these big coal trucks and we had to fill them up with coal, and then you had to run with them for about 100 yards with no shoes on in the coal mine bar a piece of wood. And then you’d hook the cart onto the line and pull it up to the top.

One lad gave up and decided to come up – of course then you hadn’t done your shift. So it was just too bad because you didn’t get anything to eat and you’d get the butt of a rifle on the end of your tail bone.

So we just had to do what we could. The Koreans there, they were like slave labour to a certain extent, they didn’t like Japanese. And the Japanese wouldn’t go down so they sent the Koreans down the coal mine with us so we could show them what we'd done.

The Japanese wouldn’t go down because this coal mine was actually against the law and it had been closed over 50 years but we had to work down it, and the shafts and the air blade and things had all gone.

And you would pant and pant and sweat as there wasn’t enough air coming down for you to breathe. And then you would be drilling and you’d hear tappings and banging, some more of our guys from another camp working somewhere else down the coal mine.

But you couldn’t send any messages because it was too dusty and dirty and wet down there. The sea was above you and the water was seeping through all the time.

When you came up they were waiting for you and marched you back and you got your bowl of rice. You sometimes said to the doctor I haven’t been to the toilet for about a month. And she’d say well you are only on your rice and that only goes to water - so you never have to go, you just have a leak and that’s your rice gone.

If you got lucky you might pick up some orange peel - or banana skin was good too but you couldn’t eat the whole lot you could just scrape that white part out and that was luxury. As I said when the marrow and pumpkin leaves were boiled you’d throw the water away and just eat the leaves, but you wouldn’t go to the toilet very often.

It was getting towards the end of the War, and we were getting pretty bony and thin. Most people were only averaging about 75 pound, nine stone. Especially the bigger guys - they suffered for it more than us the smaller guys.

Eventually two planes came over. We weren’t too far away from the local ferry boat. And we saw these two planes come over and saw them drop this bomb, which we didn’t know anything about at the time - Nagasaki was in a low spot - we just thought they'd bombed the oil well or something.

But I heard later on that there was all this churning up and smoke and we thought it was an oil well but later on we found out that it was an atomic bomb.

The dockyard around here started trembling and crunching, but we were lucky we didn’t get the heat from the bomb, but Nagasaki was in a low spot and on a bigger scale mind you. But we got the shaking and everything - we just didn’t get the heat really from the bomb because it was low down.

The Japanese came round and said that the Americans had dropped a heat wave bomb, so we were suddenly transferred out of there and they moved us to another mining camp, but only for a little while.

The Japanese said that the evening before the bombing, if they had come to some peace terms with the Americans and English, then the War would have come to an end, as there was just a little bit of fighting going on - on the border between the Russians and the Japanese.

We went to Nagasaki when we were freed and all over the mountain side the trees were burnt black charcoal just standing there.

And there was a big armament factory which they said Churchill and Roosevelt had shares in - that’s why they didn’t particularly want to bomb Nagasaki because of this big arms factory there.

But all that was left there were steel girders - just turned up like corkscrews the girders were. And all that was left of that factory was a brick chimney. The rest of the place, all the steel girders were twisted back just like corkscrews.

The rest of the city was just burning to ashes, all the villages burnt black. Then they said they’d signed the peace terms and that we would be going free pretty quick.

WWII.

Soon after the planes came over and dropped leaflets saying the Japanese surrendered so then all the Japanese soldiers, they all fled and left us to it. Soon after that the allies were looking to see if they could find us in these camps, because they didn’t know where we were.

But we painted PW on the top of the roofs and eventually they spotted us from the air.

When they had found our camps they started dropping medical supplies in big drums from Okinawa. Stuff was coming down on parachutes and a lot of them they dropped a bit too low at the start and they crashed into the earth and made big holes.

There were vitamins and tinned milk and stuff all mashed together. So everybody would dive into this hole in the ground, scrabbling to get something to eat. And they had put a bit of everything in these drums for us.

That night the officers said make sure you bring it all in and everybody was gobbling it down. There was tinned milk and chocolate and vitamins all mixed together. That night we had a big stew pot there made with all the good stuff and there was everything in that pot - fruit and tinned meat and everything you know - all mixed in together one great big heavy stew - vitamins and everything.

We had a good belly full and of course then we all had diarrhoea because we were not used to that kind of food, so we all had the runs.

Later on they dropped more supplies and some crashed onto Japanese houses so - there were some Australians there in the camp - they went out swapping this tinned stuff for meat.

I will always remember they came back with a bunch of weaner pigs, there must have been a farmer, and they brought them back and said we don’t know how to kill these. And they had them in the straw grass in this big shed, where we slept so we cut their throats and let them bleed to death and then we had this pork at night mixed up with all the vegetables.

And everyone had the diarrhoea again because [when you’ve been starving] you aren’t supposed to eat pork for a long time - because it's not good for your system after not eating anything only rice.

When the Americans eventually found us they decided to get us onto boats to go across to Nagasaki and onto the Philippines. We went for convalescence there and they fed us all kind of good food, the Americans did, Red Cross too.

And from there eventually we got a boat and they took us to Pearl Harbour and we took the dead that had died on the way there, because a lot of them were really sick and quite a few more died

We were a few days there and then we pulled out and went on the train - some went on to Australia and some went to Canada. I went to Australia and eventually we finished up in Victoria and I was in convalescence there for quite a while - but I was lucky - I recuperated pretty good in Victoria.

We finished up in New York and then went on the Queen Mary to England and were in convalescence there for a while.

Eventually they let those that were fit enough to go home to parents and relations, and the others stayed in the hospital.

So we got to England and eventually we were reunited with our families and my girlfriend Sonia was still waiting for me, she hadn’t given up on me, she’d waited for five years for me - two and half years while I was missing in action and put down as dead.

But she never gave up she still waited and she was there waiting for me, and soon after we decided to get married, and the bells rang for the first time in that village as they hadn’t rang during the War, so we had quite a nice wedding there.

The wife's parents put a nice wedding on for us, and my side of the family too and then eventually I got well enough and I started working for my brother in building contracting.

There are a few postcripts from Ray for his WW2 story:

Before the War when I boarded the Exeter she was engaged with the Graf Spey. That time I wasn't aboard, which was a good thing because the turret I was on later was blown right off.

Exeter had been in a battle and she’d got all the brunt, so later on she was recommissioned and the King and Queen came on with their two daughters.

So one of those is the Queen today.

Then Churchill came on and then that’s when we boarded her again.

We got into that convoy and stuff during the War - into Java and Africa and all around there to fight in the desert - and eventually we got engaged in another battle chased by the Bismark, another big battle ship.

We didn’t get hit but we damaged the Bismark and she went into a port in France. We all waited for her and when coming out she got damaged, and then she was attacked by the Navy and some sea planes bombed her – which finished her off.

The Bismark went down.

I want to give you a few more details of some of the things that went off in some of the prison camps I was in.

The first one was in Java. That was a real tough one. We had to work in the jungle and work 12 hours each shift and people were dying of malaria and dysentery and stuff like that.

While I was in there I had diphtheria and I finished up with malaria five times in that nine months, and after that they shipped us to Japan.

What went on in that camp, some Dutchmen tried to escape. They spoke to the Indonesians and Javanese and made some arrangement for their escape but eventually right on the border on the outskirts they tried to get on a boat to Australia - but things went wrong and the Indonesians and Javanese squealed onto the Japanese and they came out and got all three of them just before they were going to take off in the boat.

They brought them back from the jungle and they beat these three officers - and beat them to death, because they died after a few days. And then all the other guys in the same room - they had to be punished - every day - running round and round the camp in the boiling hot sun - 100 degrees [about 38 Celsius].

I don’t want to talk about everything but it was sometimes very cruel things they did to some of the prisoners. So that was the main camp in Java. That was a tough camp.

I'll tell you more about it later.

Well, Cole I suspect your Grandpa Ray never did record any more memories but maybe that’s not a bad thing. But what a lovely man he sounded in the recording.

What a story. What an experience. How does someone live through that? Kids and adults – next time you’re having a whinge about the food you’re eating, spare a thought for those POW’s who would have gorged happily on far worse than what you leave on your plate. Bully beef and hard tack biscuits eat yer heart out – baked fish entrails are where the real action is!

Thank you massively Ray, wherever you are, for your service and for recording that priceless account. And thanks to Cole Gill from Canada for taking the trouble to send it in.

Next episode

Stevie Stevens – RAF Lancaster pilot

World War Two Podcast

PS

Most of the crewmen of HMS Exeter survived the sinking and were rescued by the Japanese. About a quarter of them died during Japanese captivity. Her wreck was discovered in early 2007, and it was declared a war grave, but by 2016 her remains had been destroyed by illegal salvagers.

Grandson Cole has sent me a load of photos of Ray’s adventures, a splendid photo of him in uniform together with pics of the ship and some of the most poignant letters ever. One of his photos shows him with an HMS Raleigh sailor’s hat on, which of course is the land-based training centre he’d have started out at when he was first called up. Even today, HMS Raleigh is the largest Royal Navy training establishment in the South West of England. There’s a link in the show notes.

This is one of Ray’s letters home. A Telegram to Sonia.

Am safe in Australian hands. Hope to be home soon. [They are] writing letters and telegrams to liberated Prisoners of War, Australian Base Post Office, Melbourne. Ray

Dated 30 Sept 45 Second World War Podcast

PPS

One from his fiancé Sonia –

Sweetheart. Recd your card, lovely to hear from you. I’m longing to see you again. Hope you are well. Everyone sends love. Your loving sweetheart Sonia

So that looks like it’s the first time she’s heard from him in a long time. Possibly she’s not known if he was even alive. I’m putting one or two letters and photos in the show notes but all of this stuff is going on the WW2Talk.com forum where we can let the experts mull over the content of some of the excellent photos from Ray’s album. There’ll be a link in the show notes.

This is a WWII war podcast and WW2 podcast about great unpublished war history

PPPS – OMG!

One more letter to read out, and you will never guess who it’s from:

Sept 1945

Dear Mr Fitchett

The Queen and I bid you a very welcome warm home. Through all the great trials and sufferings which you have undergone at the hands of the Japanese, you and your comrades have been constantly in our thoughts.

We know from the accounts we have already received how heavy those sufferings have been. We know also that these have been endured by you with the highest courage.

We mourn with you the deaths of so many of your gallant comrades.

With all our hearts, we hope that your return from captivity will bring you and your families a full measure of happiness, which you may long enjoy together.

George R I - which stands for “Rex Imperator” or “King and Emperor”

So there you go – a letter from the King of England himself.

The letter has a Buckingham palace header and also has the King’s badge attached which is like a little silver seal on a piece of string or wire.

As an epilogue to the story I checked a few facts with Cole over in Canada.

He told me Ray had three children with wife Sonia, who’d waited for him for over five years:

Coles mother, Carmen, plus Dave and Colin and Colin died tragically, saving a friend from drowning.

Ray had six grandchildren of whom Cole is the eldest

“Ray, my grandpa and Sonia , my grandma, are buried in High River right beside Colin.

“Sonia, my grandma was a nurse in London in the war and wouldn’t talk about it when we asked her.

Grandpa told me Sonia was in London during the Blitz in 1940 and that sometimes the bombs came so close that some of the people that were pretty much dead would wake back up screaming. Cole and anyone else interested in the Blitz – catch up on episode 13 UXB – it’s all about the London Blitz and it’s a cracker in more ways than one!

Grandpa, Ray Fitchett, unfortunately passed away in 1998 at the age of 82 - he was always able to fit into his uniform for every Remembrance Day service or in any parade he was in or when he went out to speak about his experience in the war.

…

You’ve been listening to the Fighting Through WW2 Podcast, Episode 42 Ray Fitchett – Great Unpublished WWII History –

Thank you for your support and thanks so much for making the time to listen to me. Do hear me again next time and till then, please do your best to support the show by telling one friend about the FTP!

I'm Paul Cheall saying

Bye bye now!

This was a second world war podcast and world war two podcast depicting great unpublished war history

This podcast covers WW2 and WWII, World War II and more

Companion website at http://www.Fightingthrough.co.uk

Featured Episodes

If you're going to binge, best start at No 1, Dunkirk, the most popular episode of all. Welcome! Paul.

PS. Just swipe left to browse if you're on mobile.