76 Christmas at War 2021 WW2

More Christmas wartime cheer

- This Christmas in the South Pacific would be far more festive than last time.

- Three US soldiers came upon a small cabin in the woods.

- We followed the side of the bomb and found a second fuse

A few more yards. I clambered onto the train – Yess!

- Our Christmas Mission Was to fly Chinese troops up North!

- ’Twas the night before Christmas and all through the tent, Not a creature was stirring, the rats had all went.

More Great Unpublished Christmassy!

Reviews on main website

https://www.fightingthroughpodcast.co.uk/reviews/new/

Apple reviews - https://itunes.apple.com/gb/podcast/ww2-fighting-through-from-dunkirk-to-hamburg-war-diary/id624581457?mt=2

Follow me on Twitter - https://twitter.com/PaulCheall

Follow me on Facebook - https://www.facebook.com/FightingThroughPodcast

YouTube channel - Loads of my own videos - Dunkirk Mole, Gold Beach, much more. https://www.youtube.com/user/paulcheall/videos

Munich WW2 bomb blows up near station, wounding four

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-europe-59487910

Interested in Bill Cheall's book? Link here for more information.

Fighting Through from Dunkirk to Hamburg, hardback, paperback and Kindle etc.

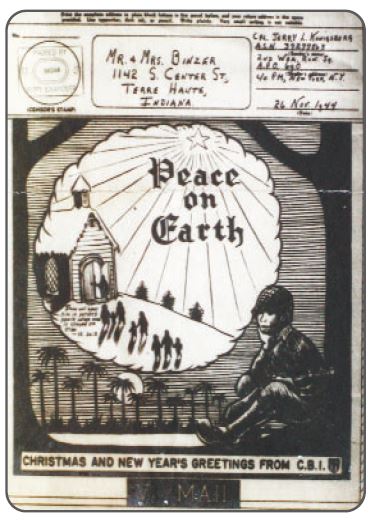

Christmas Card from China WW2

Makeshift homely christmas fireplace WW2

No shortage of Christmas guests amongst the American Seabees in WW2

Seabee gifts

5 Charlbury Grove as it is today. Throwback to WW2 London Blitz

Link to 5 Charlbury Grove sales details

https://themovemarket.com/tools/propertyprices/5-charlbury-grove-london-w5-2dy

View of rear garden and what was probably the music room during WW2!

Munich WW2 bomb blows up near station, wounding four

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-europe-59487910

Transcript

Fighting Through WW2 - Episode 76 – Christmas at War

More great unpublished Christmassy! WWII

’Twas the night before Christmas and all through the tent,

Not a creature was stirring, the rats had all went.

The helmets were hung by the foxhole with care

In case a few Zeros might buzz through the air.

Intros

Three American soldiers, one badly wounded, were lost for three days in the snow-covered Ardennes Forest. On Christmas Eve, they came to a small cabin in the woods.

So our Christmas Mission had no singing in a choir, nor cookies - but involved flying Chinese troops up North!

Blood was pulsing in my ears. Fire raged in my chest. A few more yards. I clambered - ker lam bed - onto the train – Yess!

Our second Christmas in the South Pacific would be far more festive than the first. For a couple of hours that perpetual anxiety of war was nearly forgotten.

Fade in ticking

We followed the side of the WW2 bomb and found a second fuse: Our stethoscopes indicated both clocks had stopped. And they were prone to stopping about 2 seconds from doomsday.

Welcome

Hello again and I wish you a festive WW2 welcome to the Fighting Through second world war podcast.

I’m Paul Cheall, son of Bill Cheall whose WWII memoirs have been published by Pen and Sword – in FTFDTH.

The aim of this podcast is to give you the stories behind the story. You’ll hear memoirs, and interviews with veterans in all the countries and all the forces.

This episode

I’d like to start by offering my warmest possible thanks to everyone who has supported the show at any time. You’ve brought great strength to my back to keep ploughing on with things and I want you to know I appreciate it deeply. And particularly during Covid, I hope my small contribution to your lockdown sanity has also helped you as much as me.

So, I wish you well in a successful conclusion to the covid crisis next year. And I hope you start January having had a great Christmas and with the sun on your backs for 2022.

On this festive occasion, I am so excited – again - because I really have got a truly cracking set of seasonal stories to share with you, with extracts from The Battalion Artist Seabees book and The Last Bullet German Boy Soldier. We’ve got a brilliant Aussie contribution from veteran Les Cooke and a special preview of the next episode on the China-India-Burma route based on a book by Rainy Hovarth about her father’s war - Robert Binzer.

And we’ve got a special Christmas report from the front lines from Sergeant Eoin McKewan. Ho Ho Ho!

The PS is a little heard story of second world war truce between warring soldiers. As usual, have your tissues ready! Stay tooned! And stop press, on top of all that I have some great news to share with you.

Buy me a coffee 1 - Todd Kehoe Wyoming USA Calvados

Many thanks to Todd Kehoe Wyoming USA for your Calvadosic Contribution to the show.

And hot off the stove, Mr Devin Hupp from Ohio USA has kindly sponsored me for the Full Monty award on Patreon. Devin thank you so much.

Survey Comments/WWII feedback

And thanks to worktime listener Eric Shields from Ontario, Canada for completing the show survey on the home page at FTP. I hope you have as much fun pronouncing your surname as I do Eric. Though I think Cheall is probably worse.

Tom Vrana Illinois – many thanks for your idea to cover the resistance movements – if anyone has any family stories on that front do write in please..

Feedback and WW2 Family Stories

Feedback 2 – Israel Salinas

Absolutely love your podcast and the history it provides!

It warms my heart, much love and respect to you for continuing so many brave men and women's legacies.

Your friend, Israel Salinas from Riverside California

Shoutouts – Vas

Here’s a comment from a recent review that appealed - Paul Cheall could read the phone book and I would get inspired. Whitey's Ghost from Japan on Apple

OK - moving on …

Able, Jim, 33100 Manhatten Drive, California – Tel 06134888

Able, Carol 522 Oklahoma Dri – No?

Maybe not eh, Whitey.

Old ‘uns but good ‘uns!

Greg G.

says “My grandfather was U.S. Army in the 695th Armored Field Artillery Battalion, which was attached to various units that fought in France in Normandy, Lorient and Metz, and also Germany. He never spoke much about it, but I'm working to pull together a short history for my family. Thanks for all your hard work.

Greg in Atlanta, Georgia, USA.

TR

Brian Moss – Bomb Disposal

I’ve been scouring my podcast files for any past or future Christmas stories that I haven’t used yet. And I just cannot resist sharing this extract from the unpublished memoirs of Sgt Brian Moss of the Royal Engineers. You’ve heard from Brian before with his adventures on bomb disposal during the London Blitz Ep 13, blowing up the anti-tank ditch at Wadi Akarit in North Africa Ep 2 and storming the beaches of Normandy Ep3 with the 5th East Yorks. If you’ve not listened to these stories yet, start off with the Blitz because they really don’t get much better than that. One day I’m sure this man’s memoirs will be published in full and a shiver is going up my spine as I say this because they are brilliant.

Talking about old episodes, my stats tell me that later episodes of this WW2 podcast are attracting more downloads than the earliest ones. That means you are definitely missing out on some of the finest material this show has ever offered, so without boring you with the details, get yourself into the FT WW2 Podcast early material and get bingeing.

And just a polite warning that at some point in the future I’m expecting a tranche of these episodes will go private on a subscription only basis, so I’d recommend downloading as many episodes as you can to keep now, listen later.

Over to Brian in Bomb disposal …and what I love about his writing is how he gets into the nitty gritty of bomb disposal – with all the old world skills and knowledge of how stuff worked – and I’ll warn you now – don’t get too close over my shoulders while I’m reading this – because a bomb just might go off.

This takes place in the lead up to Christmas 1940 – yeah – near enough. And it’s the most exquisite piece of writing, so settle yourself down with a warm cup of hot chocolate and a Calvados. This chapter from Brian’s book is called:

Number 5, Charlbury Grove

and this is in London during the Blitz when Hitler’s Luftwaffe was trying to bomb us into submission.

“The Charlbury Grove job started the same day as the Northfield Avenue bomb. It had fallen on October 7th, as had others nearby. It seemed very likely that this bomb had a delay fuse, since the others in the same stick had not gone off until several hours after having fallen. For a month I would spend nearly all my time on this single job. It was thought to be a big bomb.

I was the first UXB person on site, and a Special Constable showed me No. 5, before quickly withdrawing to leave me alone. Charlbury Grove was definitely a higher-class neighbourhood. The houses stood on the right hand side of the road facing east. On the other side of the road was a high wall, behind which was a Convent. No civilians were in sight; the entire street had been evacuated so it seemed I had the neighbourhood to myself. The front door to No. 5 was open. A tile floor in the hallway was damaged, but I couldn’t determine whether this was the point of entry. My lads arrived and I set them to look around. I was quite sure that the occupants of No. 5 would know where the damned thing was but where were they now? Who were they, I wondered?

The hall contained a fireplace as shown in my sketch. In front of the fireplace, the carpets and floorboards were displaced. Beneath the living room was a cellar and, down there, I noticed a mess in the soil floor that might indicate the passage of the bomb. I then explored the upstairs. It was a three-story house and, as I climbed up the highest flight of stairs, I saw a large round hole in the roof. I found another hole in a bedroom floor, and traced the trajectory downwards. It had passed through the floor of the hall, in front of the fireplace, and then down into the cellar.

We set to work. We ripped up the floorboards in the hall. Many wine bottles in the cellar had to be moved aside, or otherwise dealt with.

In fact, over time, most of them were otherwise dealt with. He he!

My team comprised six men; had there been any more we would have been in each other’s way. I kept three men working while the others rested by the truck, one hundred yards up the road. They swapped duty every hour. It was necessary to keep the second squad at hand since their job would be to help (if help would be of any avail) if the bomb detonated under us.

We dug down about ten feet below the cellar floor and found the fins. I was taking out a shaft about six feet square. The wall between the living room and the hall was directly above the centre of the shaft. It was astonishing that one could excavate under the footings of a brick wall without the thing collapsing on top of us. We had no timber, nor the time to fix it in position to support our excavation. Several days later, when it was obvious that this was going to be a long job, we started to shore up the footings with timber we found somewhere.

The man I recall most clearly on this job was DW Shepherd, who did most of the digging. Berridge, Forrester, WF Davies, Rodwell and others were also involved. Our shaft followed the bomb’s path downward, like the journey to the centre of the earth, or so it seemed. The end of the first week saw us twenty feet down and still sitting above a thousand pounds of explosive which might at any second send our dismembered bodies into orbit. We reached the base of the shaft by rope ladder, slung from the joists of the living room floor. A bucket and rope were used to bring up the excavated clay. Two rooms of the house were already full of clay so we started to fill the hall, and then the front garden.

It was very dark twenty feet down below the floor of the cellar. No power existed, so we lit an enormous acetylene lamp, as big as a dustbin, at the bottom of the shaft! Asphyxiation was the chief danger. We tried pumping air down by hand before discovering that so great was the uplift [FROM THE RISING] of the hot, foul gases, that [we discovered] a length of pump suction pipe extending from the front garden to the bottom of the hole automatically supplied fresh air [down] to the [person doing the digging].

I had the opportunity to study London clay at length. This clay is dark brown, containing tiny brilliant chips of mica. It is also hard, which was just as well in view of our timberless hole. No power on earth would now get me to permit men to work down a hole like that. Yet the hole would eventually become twice as deep.

Number 5 was not looking at all like it did when we took possession.

Mounds of clay were piled everywhere. The lads, in good humour, had handled some of the articles in the house. I couldn’t blame them. They were trying to save the house and remove the danger at the risk of their own lives and I don’t know how you put a price on that. I wondered who would foot the bill after clearing away our mess and reinstating that awful hole of ours under the foundation.

On the 1st November, my Section started work on a stick of 50 kg. bombs that had fallen in the Harrow area of London. I was not involved but asked for one to be brought intact to No. 5 where I was lodging. It was a 15-fuse bomb, complete with fins. I burned it out in the back garden of No. 5. Then I sought the assistance of Harry Lovell, the HQ store man who made cigarette lighters and engraving tools from electrical bells. Harry quickly constructed a crate for my trophy bomb and I took it to Euston station.

I had addressed the crate to my father in Haslington. “What are the contents?” asked the dispatcher, licking his pencil. “Empty bomb case for instructional purposes”, I replied. I cannot recall the expression on his face but off the crate went. A week or so later, my mother wrote to inform me that two LMS men had delivered the crate. Unfortunately the crate had broken open at that moment, disclosing the contents. The two men ran away, leaving my mother with a bomb in the front garden and wondering what on earth her son was playing at.

In 1948, after the war and my return to civvie street, I buried the bomb case in the backfill of my six-foot diameter Leighton Valley storm water sewer. If it is ever dug up, some unanswerable questions will be asked.

Meanwhile, our shaft continued deeper. We were now thirty feet deep, and still the thing went downward. At lunchtimes we were now invited into a house in the road running at right angles at the western end of Charlbury Grove.

We ate lunch in a large garden shed that was equipped as a workshop. The lady of the house officiated and allowed me the use of the workshop to unscrew gaines [or booster charges] from fuses and to dissemble difficult fuses. At this time I made my own little contribution to science. The kilo elektron bomb was then being scattered liberally all over London, by the enemy. They came in suitcase-like containers, which opened as they fell from the aircraft, rather like the butterfly bomb. The kilo elektron was so called because it weighed 1 kg. It was made of elektron, an alloy of magnesium, and was the standard enemy incendiary. An impact fuse initiated a thermite mixture, which caused the metal body of the bomb to burn furiously with an intensely white flame. People used to come up to us in the street and say, “Come and look at what’s in my back garden” and so on. On most days we had a selection of stuff that had fallen from the skies.

I was going through my ‘in-tray’ one day and of the half-dozen kilo elektrons, one stuck out a mile. On the end opposite to the fins was a letter ‘A’ painted in red. I wondered if ‘A’ stood for ‘Achtung.’

Listener of course having recently listened to veteran Ken Cooke we now know the A is the designation for where the bomb was manufactured, which was the place Ken and his pals could never seem to locate despite all the signs – Achtung Minen.

Before attempting to unscrew the middle joint, I looked at the fins. They appeared to be normal. However, something made me gently lever them off. The three little rivets gave way, and off came the fins. There, coyly hidden, screwed into the back cap, was an ordinary gaine, full of the highly sensitive penthrite wax. The idea was that as the bomb started to burn, the penthrite would get hot and explode, spraying people nearby with molten magnesium. I made my discovery known to HQ, but never heard any more about it.

In later years, in my job at the Civic Offices, Swindon, I would be labeled as devious. However, I had learned from experts in the creation of devious devices.

At forty feet down, Shepherd yelled up to me, “It’s turned!” I raced down, and sure enough, the vertical tunnel drilled by the bomb had turned horizontally, and was now going towards the back of the house. “It won’t be long now,” I said. Digging horizontally into a hole that had somehow shrunk into a 3’6” diameter section was not easy. I obtained an earth auger, and we drilled with it.

The room at the back of No. 5 always intrigued me. It had full-width French windows and was heavily and expensively curtained. Part of the room was raised, in the form of a small stage. Perhaps it was a music room.

We decided not to put clay in there.

Anticipating that we would find the bomb soon, I got out my stethoscope and prepared to listen to a clock. Lt. Ewart turned up with his gear, and on November 27th, 1940, we found the bomb. After the forty-foot vertical plunge through London clay, it had traveled another fourteen feet horizontally. It was a 500 kg bomb, with a No. 17 fuse.

Listener 500kg, think of it, that’s like 25 heavy holiday suitcases! And these bombs were over 3 metres long. So a far cry from the 2” mortar that my Dad carried on D-Day which weighed just 2 lb, 1 kg!

START CLOCK

As we investigated very carefully further along the side of the bomb, we found a second fuse: another 17! (Sometimes fuses were located under the bomb, and that was extremely difficult).

Our stethoscopes indicated that both clocks had stopped.

This type of clock was prone to stopping about 2 seconds from doomsday.

We slapped on a clock stopper. This was a heavy electromagnet in the field of which all clocks were forbidden to run. So far, we had been lucky.

The chances were slim enough that both clocks had stopped, and it seemed even less likely that neither would fail to restart, as we worked upon the bomb.

In view of the Zus 40, [anti-handling device (Or booby trap) often fitted to munitions, the fuses could not be withdrawn. A specialist team arrived, trepanned the bomb case, and injected steam. This melted the TNT and blew it out of the bomb like sticky toffee.

All this

was at the bottom

of my crazy

un-timbered shaft.

PAUSE

STOP THE CLOCK

The following day I was kicking my heels in the road outside, when several officers arrived, escorting a singular figure. This was the Earl of Suffolk. As I helped him down the rope ladder, I recall seeing flecks of red blanket or red wool in the long hair at the back of his neck. After an hour of special incantations and other ministrations, our bomb was defused. And that was that. I have often wondered how No. 5 fared. If you are ever near Ealing, please take a look for me, and wish it well.

In the autumn of 1940, London was a wonderful place. The spirit of the people was fantastic. It is very possible we shall never see its like again. The Panzers were poised only 22 miles from the fields of Kent, and could clearly be seen as the enemy without. Will we respond so magnificently to the enemy within? I think not.

Just after Christmas 1940, which we celebrated in the White Hart pub, Acton, everything changed. We stopped work on bombs and were put on weird jobs in the City, such as helping in a Bank incident. I recall scores of mink coats being recovered from the mud of a hole in Oxford Street, with police detectives watching all the time.

Obviously something was afoot.

And there we’ll leave it. Thanks to Brian Moss son Mike who lives out in Canada for his help in bringing his Dad’s memoirs to the fore. Just magnificent writing.

And would you believe I Googled the address for this house and found an estate agent’s entry for it. It really is rather a grand-looking house and I’ve put photos and link in the shownotes. You’ll see the frontage and also that rear facing lounge that might have been the music room that Brian mentioned. I’m sure you can see a few stains on the lower walls where Brian dumped some of his excavated clay. There’s one or two empty wine bottles lying around too – but they can’t be Brian’s – can they?

But hey not bad for 2.3m huh? And that’s pounds sterling by the way!

And spookily on cue I’ve just been reading a BBC news article on a WW2 bomb going off in Germany

Munich WW2 bomb blows up near station, wounding four

Link

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-europe-59487910

Four people were hurt, one seriously, when a World War Two bomb blew up on a railway construction site in the German city of Munich.

The fire brigade says it happened during drilling work near Donnersberger Bridge, close to the main station.

As a result rail traffic in much of Munich was brought to a standstill.

Unexploded wartime bombs are frequently found in Germany and prompt big evacuations, but most are defused by experts without exploding.

Police say the bomb went off during tunnel work near the bridge. Local reports described a loud bang followed by a column of smoke. An excavator was overturned by the force of the blast.

Emergency services rushed to the area and bomb disposal experts were quickly at the scene examining the remains of the bomb.

Rail operator Deutsche Bahn suspended travel to and from the central station but police said some long-distance lines had already returned to service.

Bavarian Interior Minister Joachim Hermann said the "aerial bomb" weighed 250kg (550lb).

There’s a really important bit of news on this story that I’d like to share with you now. I’d like to … but I’d prefer to leave it to the end of the show. So tune in to the PS’s and you’ll find out. All I can tell you is I’m grinning like a Cheshire Cat right now.

Eion McKewan diary

I’m now going to give you a flashback to the memoirs of Sergeant Eion McEwan -5th Scottish Para WWII memoir fighting in Italy.

You might recall listening to the memoirs of Eoin in episode 38.

I’ve pulled out a few fleeting memories which he recorded for posterity, and collectively they kind of ground us to a sense of what’s important in life when all around us seems to be going to heck. Because these boys definitely didn’t have it good.

(as an aside, Dad would have recently got back to England from the fighting in Sicily and that’s when he had to go and see the families of his fallen comrades before he was whisked off to start training for D-Day – but right now it was someone else’s turn to pick up the battle)

Eion Owen McEwan - Italy

CHRISTMAS DAY 1943

Bully and Biscuits for breakfast - in trenches day and night - pouring with rain

Monday 26th Dec Marched seven miles in sleet and rain to Castel De Sangro

Wednesday 30th Dec Moved further back to Castel Frentano 6 miles

Friday 1st Jan 1944 Snowed up - had to clear one mile of roadway to get rations through

Saturday 2nd Jan Went to assist "C" Company out of snowed up position

Sunday 3rd Jan Moved into concentration area Lanciano

Monday 4th Jan Moved up between N.Zealand and Canadians - near Pescaro. Pinned down and could not move during daylight hours (freezing) could not have any hot meals or drink

Saturday 9th Jan 1944 Lt Brammall shot in leg whilst on reccy

CHRISTMAS DAY 1944 Glorious morning and it seems very quiet today (Thank God). On guard duty for only one hour 0900-1000. Strange - but had quite a nice day, had a good dinner and plenty to drink.

Boxing Day Briefed today on a session of house clearing tomorrow. Tanks in support.

Wednesday 27th Dec Cleared a very large area - took many prisoners, also found lots of weapons and arms. Cpl Thomas killed - Lt Brammell and Sgt Walker wounded

Thursday 28th Dec House clearing again - captured many more prisoners. Sergeants Scrimgour and Crow injured (main Pierous Road)

4th Battalion attacked tonight but they easily repelled this attack

Friday 29th Dec Billetted with the Military Police for Athens - had a nice drink of Cognac. General Alexander complimented our Battalion for the job we had fulfilled in Athens. Curly Braeburn killed, Shanks injured by sniper

Saturday 30th Dec Company Commanders orders today - asked to accept promotion

8 and 10 Platoons went to clear a couple of blocks, we provided covering fire. Came under heavy mortar fire from Greek People’s liberation army (one officer wounded and many civilians)

Sunday 31st Dec 1944 Brought the New Year in, in grand style. Had a party and the people we were billeted with brought out some very old champagne and some lovely liquers.

Monday 1st Jan 1945 Started off the New Year with a glorious day and peace terms imminent - good billets and in good health. Ginger Statham and Bill Cairns joined us tonight

Eoin – thanks for your service.

Family stories 1 - Raymond Gawthorne from Arizona via the web site

I love ww2 and your podcast. My father Frank H Gawthorne was in the war from 1939 to 1945. He was 15 years old when he joined the Royal Canadian Navy. He spent his time on a corvette, Q boat and river class frigate fighting in the North Atlantic. He was a great father and I bet a great sailor.

Raymond Gawthorne.

Raymond - thanks so much for that comment and you might like to know that I'm currently working on a Memoir which I've been sent on the North Atlantic war which I hope to use in an episode some time next year so keep your ears peeled Sergeant, but it’ll be a while yet.

War stuff 1 – Alan?

Don’t know if you’ve watched the excellent film “The Forgotten Battle” on Netflix?

Features the British Army’s post-D Day Battle of the Scheldt in the Netherlands. Very realistic battle scenes, and an accurate portrayal of 1944 British army uniforms, helmets, berets, jackets etc for both Paras and Infantry, which most War Films tend to get wrong.

A good film

Alan

TR

Rainy Hovarth - Robert Dean Binzer

Christmas Card from China - 1944

Today’s feature story is taken from The Able Queen Memoirs Of An Indiana

Hump Pilot - Lost In The Himalayas

The book was produced by Rainy Horvath about her father Robert Dean Binzer and based on his testimonies.

Wiki - The Hump was the name given by Allied pilots in the Second World War to the eastern end of the Himalayan Mountains over which they flew military transport aircraft from India to China to resupply the Chinese war effort of Chiang Kai-shek and the units of the United States Army Air Forces (AAF) based in China.

Rainy explained that her father was in the cockpit on a mission in China flying supplies, arms and soldiers behind enemy lines with the famed 14th Airforce backwards and forwards over the Himalayan mountains, under fire and through hellacious storms.

So here’s just one chapter from this book

“Our base at Yunnani, China had planned for a

choir to sing at a service for Christmas. Tom Quigley

and I signed up for the choir and we had attended

a couple of rehearsals. We were looking forward to

the concert but disappointed to learn that [over Christmas] we would

be on detached service at another base located at

Chanyi (Zhanyi), just Northeast of Kunming.

We took off and arrived at Chanyi where we

found out we were to carry Chinese troops up North

to Chengtu, where our B-29’s staged out of.

These Chinese soldiers needed to be flown back North to

help the 14th Air Force protect their air bases which

were North of our location, and we had flown this

route many times. The only problem was that we

had no parachutes for our passengers, as required

by regulation.

We raised our concerns, but we were told to go

ahead and take all the Chinese with us, regardless

of parachutes. This we did, and fortunately we had

no problems this trip, so we were never faced with

the problem of what to do with the Chinese IF we

had been forced to bailout. But it was always on our

minds. Now the troops were loaded up, all seats

filled, and the floor was also filled with as many soldiers

as could be fit in, shoulder-to-shoulder. None

had parachutes. If any had ever flown before, it was

in one of our transports.

Our own parachutes were carefully removed from

the rear of the airplane and placed in the forward

compartment where the radio operator was located.

We were not too happy to be flying 50 or 60 non-

English speaking armed soldiers, all seated behind

us blocking the doorway and all carrying rifles. We

assumed no ammunition, but we didn’t ask them.

So, this was to be our Christmas Mission, no

singing in a choir, no cookies, and not a mission we

would have selected on our own - but the trip went

well except for the mess in back where several of

the Chinese soldiers got air sick.

After we unloaded

our passengers and got the plane cleaned up and

returned to Chanyi and picked up another full load

of Chinese soldiers, also without parachutes, to take

up North and we made another round trip.

It was not the best Christmas ever, but we did get

a Christmas ration of a six-pack of beer, and maybe

a bottle of whiskey, that was issued to us upon

our return from the first trip North. At this point, after

returning from this mission we learned that our

Squadron was to be moved to another base closer

to Kunming.

We would now call Chungking our new home

base and would fly our missions out of that base,

South of Kunming, just beyond the Lake. After our

service at Chanyi ended we flew into our new location

at Chungking where I found that I shared a room

with only three, instead of the four in a room like we

had at Yurmai (Yurman).

And the Christmas Card from China is what I used for the artwork for this episode. There’s a bigger copy in the shownotes at the WW2 website.

Rainy explained to me that her Dad actually sent that card home from China. “It's still in my late Grandmother's photo album. It was his real card. Of course what was sent was what was called an airgraph of the original, a sort of shrunken photocopy in order to save space and weight for transportation.

Catch the next episode if you want to learn more about the Aluminium Trail and Rainy’s Dad’s war, and what happens to him later in the war – spoiler alert – he ends up crashing in the jungle. If you can’t wait and you want to get a hold of Rainy’s book now for Christmas, look up The Able Queen Memoirs Of An Indiana Hump Pilot by Rainy Horvath.

TR end

Les Cook – Christmas story

Corporal Les Cook was in the second 14th in the Australian Imperial Force AIF. And he served in Greece, Crete, New Guinea, Borneo and in the occupation forces in Japan.

He’s regaled us with his stories of war throughout this last year and he’s not done yet because I kept one or two stories back for a snowy day just like today (I wish)

Here’s an absolute beaut I’ve been savin for all you inhabitants of Canbra n Melbin and whatever that other place was I was mispronouncing last time!

This is called:

Practical joke gone awry.

It’s kind of cruel at one level but it has a happy and righteous ending. And you’ll have to forgive me if I can’t stop laughing half way through.

Here goes

Practical jokes are an integral part of every workshop environment, and mostly they are good-natured and are accepted as a part of life. It is axiomatic however that the victims whose reactions are the most spectacular are picked on more than others.

Alf Moreton was as satisfying a reactor as one could hope to find, so came in for more than his fair share of pranks. Alf was a bit of a rough diamond. He was a general roustabout, whose duties included making the tea and keeping the lunch-room clean and tidy at the old Ministry of Munitions complex in the Footscray - Flemington area of Melbourne. It had been there for many years, and so had Alf.

As an example of these jokes, one of the men brought a pair of shoes to Alf asking "When you're down town today will you drop these off at the bootmaker's and get them half-soled for me please?" Looking at the shoes with disgust Alf said "I'm not going to carry the dirty things down the street like that - wrap them in some paper and I might think about it”.

Now cats were kept in the warehouses to control the mice. The cats ran wild and they bred prolifically, as cats do. To keep the cat population down to a manageable size it was customary to drown most of the kittens at their birth. Several kittens had been despatched that day and the shoe-owner wrapped their soggy wet bodies in some newspaper. He gave the parcel to Alf saying "There, I've wrapped them as you asked - now will you take them?"

Alf walked into the bootmaker's shop, threw the parcel onto the counter and said in his gravelly voice "Half-sole them". The bootmaker opened the parcel then chased Alf out of the shop and along the street throwing the drowned kittens at him one at a time. We got this part of the story from the bootmaker - Alf didn't have much to say on the subject.

There are some occasions however when the biter is bitten. One Christmas eve a few of the men decided to play a joke on Alf. They purchased a cheap wallet and, using a Bank withdrawal slip, they wrote the words "Pay Alf Moreton five pounds", stamped it with the Flemington Social Club rubber stamp, and scrawled a signature on it. The bogus "cheque" was folded into the wallet which was then wrapped with Christmas paper.

Somebody made a short speech at morning-tea time thanking Alf for his efforts over the past year and made the presentation. It was here that the joke went wrong - or right depending on how one looks at it. Everyone thought that Alf would see immediately that the "cheque" was a fake and would abuse them at great length, which was his usual reaction to people ribbing him. This would give everyone a good laugh and the whole thing would be forgotten.

It didn't happen that way! Alf opened the parcel and saw what he believed to be a cheque in his name for five pounds which, in those days, would have been a week’s wages for him. He thanked them for the gift saying that he had only been doing his job, but that he was very grateful for their generosity. It was too late to undo what had happened - nobody was prepared to disillusion him.

Throughout the rest of the day Alf stopped every driver leaving the Depot asking for a lift to Footscray so that he could cash the cheque. All the local drivers, being in the know of course, had excuses why they couldn’t help him. Late in the afternoon he struck a South Australian driver who had come in that day and was leaving the same day so that he could be home for Christmas. This man would not have known of the joke and agreed to drop Alf at Footscray on his way through.

Before the war, and for many years after, tobacco and cigarettes were obtainable only from a Tobacconist. I don't know if this was the result of Government regulation or if it just happened that way. Invariably this business was combined with a men's hairdressing service, the whole being referred to as a Barber's Shop.

As were many other things, tobacco and cigarettes had been rationed during the war. Ration coupons were issued to individuals and these were collected by the shop-keeper as each purchase was made. One of Alf's unlisted but apparently voluntary tasks through the war years had been to purchase tobacco and cigarettes for the men at the Depot. He had always patronised the same barber's shop in Footscray so the barber knew him well.

Arriving in town and finding the banks closed, Alf made his way to the barber's shop. His failure to identify the fake cheque indicates that he did not have a cheque account, but it is probable that he had had cheques for others cashed there, and it would have seemed to him to be the best place to go.

The barber's school-age daughter was behind the counter; the barber was at the back of the shop cutting somebody's hair. The barber looked up when Alf. came in saying "Gooday Alf - what can we do for you?" Holding up the bogus cheque Alf said "The blokes have given me five quid for Christmas, but it is in a cheque and the banks are shut, will you cash it for me?". The barber replied "Yes - of course I will". And he said to his daughter "Give Mr. Moreton five pounds out of the till". She did this and, apparently without looking at it, she put the folded bogus cheque in the till.

Back at the Depot the men waited with mixed feelings. It hadn't been meant to go this far and more than a few were suffering pangs of conscience. All expected that Alf would be ropeable. Great was their surprise when he came in smiling all over his face and still vocal in his thanks for their generosity.

We learned the full story of what happened at the barber's shop when the barber came to the Secretary of the Social Club after the Christmas/New Year holiday break saying "You've had your little joke - just give me the five quid and I'll say no more about it".

BATTALION ARTIST

Nat Bellantoni

A - Batallion Artist - Merry Christmas 1943 pic xmas 1

Moving to the South Pacific now for the war against Japan. In episode 71 we learnt how the 78th Construction Battalion fought their war with spanners, saws and supreme engineering savvy, providing the American troops out in the far East with everything they needed to fight and survive. They built airfields, docks, roads and much more to keep the military wheels turning.

The Seabees of the 78th certainly had some rough times and would wait nearly two years to celebrate winter holidays with their families at home.

On Christmas 1943 they unloaded the biggest shipment of mail they received

while overseas; on Christmas 1944 they held services in an improvised shelter on a baseball

field in New Caledonia.

It was mid-December 1943. On December 21 Nat would turn twenty-three. Four days

later, it would be Christmas. But it would be unlike any Christmas he had ever known. No

presents. No family. No fabulous Italian meal. Instead, Christmas would be a workday like

any other. There was a base to be built. And a war to be won.

SLEIGH BELLS

But Nat wasn’t to be totally put off demonstrating at least some kind of festive spirit and he spirited the following poem from somewhere:

This is called Jungle Bells

’Twas the night before Christmas and all through the tent,

Not a creature was stirring, the rats had all went.

The helmets were hung by the foxhole with care

In case a few Zeros might buzz through the air.

The soldiers were sleeping, dreaming of things

Like vine-covered bungalows and wedding rings,

Of beautiful blondes and thick juicy steaks,

Of sundaes and sodas and Mom’s chocolate cakes.

An air of contentment crowded the place

And satisfied smiles were on each GI’s face;

The stockings were nailed to the center pole tight,

Moldy and green in the faint evening light.

Whether home or in jungle, this time of the year,

Living secure or in perpetual fear,

The holiday spirit stands out like a light,

A symbol of justice, of right over might.

So they slept. Their thoughts were the same:

They saw all their dear ones and called them by name.

May your Christmas be merry and the coming year find

Dear ones together—the war far behind.

—Author Unknown

The guys got a chuckle out of this poem and passed it

around. Eventually, Nat made himself a copy. Before tucking

it between the pages of a sketchbook, he scribbled a note

across the bottom:

More truth than poetry!

In a recent interchange I had with Janice she added:

That poem speaks to the staunch determination of all those wonderful men of the US, UK, and ANZAC forces--and the irrepressible humor that helped them cope.

Janice

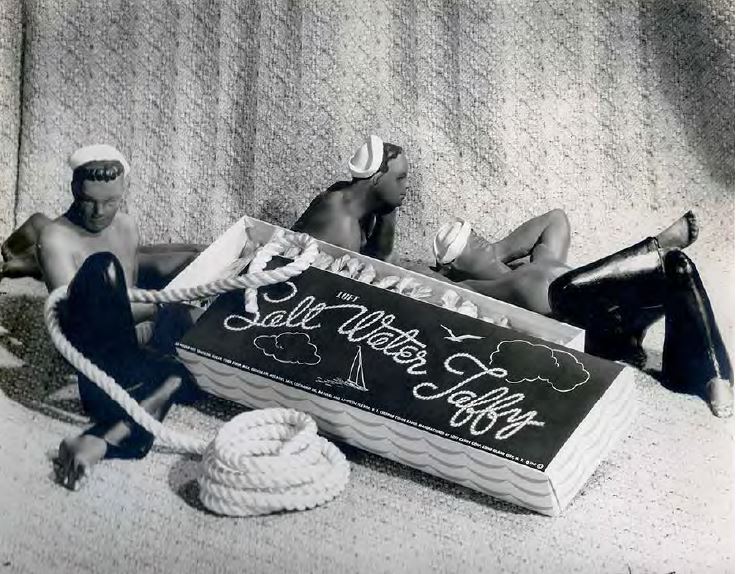

P.S. On the two-page Christmas spread in "The Battalion Artist," what speaks most eloquently of the characteristic "Can Do" attitude and ingenuity of the Seabees is a photograph on page 41.

When you look closely, you can see that the fake fireplace, Christmas tree and decorations were all improvised by the men, using whatever materials came to hand!

I’ve put that photo and a few others in the shownotes.

B - Batallion Artist - INTERLUDE IN NEW CALEDONIA – pic salt water

The Seabees moved on eventually to yet another island.

INTERLUDE IN NEW CALEDONIA

New Caledonia was, literally, a breath of fresh air. They had

left behind the torrid heat of the equatorial zone.

This second Christmas in the South Pacific would be far

more festive than the first. Father Kofflin had made sure of

that. The ballfield was converted to an open-air chapel complete

with greenery and sparkling lights. Midnight Mass

was followed by Christmas morning services, turkey dinner,

Australian beer, and packages from home. And no mud!

After supper, the battalion’s best pianist sat down at the old

upright in the mess hall and led an impromptu sing-along—

everything from hymns and carols to show tunes. Nat’s voice

was among hundreds. For a couple of hours the perpetual

anxiety of war was nearly forgotten. The ache of being away

from loved ones was lessened a bit. It was not like being

home. But for here, for now, it was as good as Christmas

could be.

But as weeks and then months went by, the men lived with an unspoken sense

of perpetual anxiety—for they knew that they were inevitably

headed to their ultimate Island destination.

And there we’ll leave the Seabees.

The Last Bullet

I am using the next segment to act as a joyous reminder that Heidi‘s book is going to be published by Pen & Sword next year. When I was preparing the original German boy soldier episode about her father, I decided to be Mr ultra efficient and took the opportunity to pull out a Christmas story which Heidi is happy to share.

So her Dad Willi has been taken into the children’s relocation program in Germany and is within a hair’s breadth of becoming a hitler jungend. He’s living away from home with a German family, the Volmar’s. And it’s coming up to Christmas ….

A - Heidi - The journey home

Christmas 1943

And look out for a short cameo role which Heidi kindly played for me in this.

Christmas 1943

Christmas 1943 was approaching. Since my father worked for the Reichsbahn, the German national railways, he had access to train tickets, and one day Frau Vollmar received a letter from him with a free round-trip train ticket from Konstanz to Witten for me. The big question was, how was the traveling from Konstanz to Witten going to work? I was with the Jungvolk, the stage before becoming Hitlerjugend (HJ), the Hitler Youth, and I was also part of the KLV, the children’s relocation program. We were monitored so we would not get into any mischief. We were not allowed to travel home. It didn’t matter that I had a ticket, the HJ guards who patrolled the stations were not going to let me get on the train. My parents obviously did not realize this. Disobeying the authorities could spell a lot of trouble for all of us. I could get disciplined, taken away to a place a lot less nice, where I may have to do physical labor. My host family would probably be chastised for not being able to control me and suffer a consequence like losing food stamps. But, knowing how I longed to see my parents, the Vollmar family decided to help me.

We arrived at the train station close to the time my train was to depart, but we did not go inside. The station was bustling with people, either leaving or arriving to be reunited with their families in anticipation of Christmas. Wehrmacht police, called the Feldgendarmerie, were on patrol. We could also see the HJ guards who made sure controlled that no Hitlerjugend or Jungvolk kids snuck through without proper authorization credentials. They walked up and down the crowded platforms in their smart brown shirts with the swastika on their left arm, their field knives on their black leather belts. There was no way I could get on the train directly from the platform, the guards were everywhere. To get on the train unnoticed, I would have to get in from the back end.

We walked along the outside perimeter until we got to where we could see the tracks extending into the distance. The train I wanted to board was there. As long as the guards didn’t look my way, I would be all right. You could get to the tracks quite easily, there were no barriers blocking access. Frau Vollmar’s two eldest sons were my lookouts, they would watch out for police and Hitler Youth so I could run over the tracks to get to the train. We walked along a street that ran parallel to the tracks, a waist-high wall separating the two.

“Everybody keep walking and don’t look around you. Look ahead,” Frau Vollmar reminded us.

We complied. She did not want us to slow down too much or hesitate lest we attract unwanted attention, but luckily the street was empty. The Vollmars fell back a little, and I kept walking ahead until we arrived at the end of the train, where the low wall also happened to end. I walked just past it, slowing my pace to a stroll. Frau Vollmar kept going at a brisk pace as if on her way to an appointment. She was to meet up with the boys later, on the other side of the station. The Vollmar boys slowed down, cleared the wall and turned left off the street toward the tracks. They leaned against the wall and waited for an opportunity when the guards were not looking our way. Once they gave the ‘all clear’ hand signal – a sharp up and down movement of the forearm - I was to rush onto the tracks and jump on the last car of the train. I had to cross two sets of tracks to get to the train and I had to be fast. The guards could turn to look at any moment. My eyes were fixed on the Vollmar boys.

The signal came immediately, and I just ran. There could have been a train coming from the other side, but I didn’t care. Nothing was going to keep me from getting home.

Don’t look… Blood was pulsing in my ears. The distance was narrowing in front of me as I flew across the tracks, my legs propelling me forward as if of their own will. Fire raged in my chest. A few more yards… yes… I clambered onto the train. That is when I exhaled. I was on my way home.

Nobody seemed to have taken notice of me. Now I had to find a place to hide. I started walking past the compartments, still breathing heavily, not sure what I was looking for or how to avoid the guards who patrolled the inside of the trains. I spotted a couple of older peasant women sitting by themselves who looked friendly and decided to take a chance.

“Ent schuldi gung, excuse me,” I said to them as I opened the compartment door, interrupting their conversation.

They looked up at me with surprise. “What is it, boy?”

“I’m on my way to Witten to see my parents but I’m not supposed to, and if the guards find me, I’ll get in trouble and they’ll send me back. Can you help me hide?”

“Junge, don’t worry, we’ll get you home” they smiled and waved me in. I think it was a like a challenge for them. They looked almost excited to be able to play a trick on the guards.

The Feldgendarmerie and the HJ came by often during the trip to check on the passengers. The women’s strategy was to hide me under their long, multilayered skirts, as nobody would ever dream to look there. It was stuffy – and smelly - under those skirts, but I didn’t complain. Whenever the coast was clear, they would tell me, and I would come up for air for a while.

During the trip, the train was attacked by allied aircraft. We heard the heavy drone of the planes in the distance over the dull clatter of the train tracks, rapidly getting louder and higher pitched. There were several. They were going to shoot at us.

“Quick, on the ground, away from the window, cover your head,” urged the women. I crouched on the floor, arms over my head. They just sat where they were, heads bowed and eyes closed, hands clasped in prayer. Luckily, the aim of these planes was not good, and a lot of the machine gun shots went rattling past the train, their trail of holes and dust visible in the fields as the train kept moving. We heard a few startled cries and the scuffle of feet, but overall people were not noisy. There wasn’t a lot of commotion because people were resigned to the fact there wasn’t anything anybody could do about it, so we just remained quiet and hoped to make it. A few shots landed on the roof, but none of the bullets made it down to us.

“Thank God they didn’t throw any bombs…” sighed one of the peasant women, fingering the beads of the rosary she had been holding tight in her hand.

“Amen,” nodded the other woman. “Amen, praised be the Lord.”

I finally arrived in Witten, feeling lucky. I had made it, maybe things would turn out all right after all. Mama and Papa were overjoyed. The Christmas tree was in the living room, brightly lit with candles clipped onto its branches. My mother baked what cookies she could with the rationed butter and flour she was able to find, and their aroma permeated the house, reminding me of all happy Christmases that had come before. All four candles were lit on the Advent wreath sitting on the dining room table. Christmas carols were sung, and relatives visited. On Christmas Eve, my parents had a present for me. It was an air rifle. The barrel of the rifle was made of a polished, shiny metal smooth to the touch. I stroked the rifle with pride of ownership swelling in my chest and took it outside to try it out as soon as I had a chance. I shot at some squirrels and birds out in the backyard, but they were too fast, and I didn’t hit any. The fun was not so much in hitting the mark as it was in playing with a gun that belonged to me. I had never had something so valuable before.

This was all I wanted. I was home with my parents and never wanted to leave again. It was as if for a brief interval time stood still and everything was all right. But the inescapable reality set in that I had to return to Konstanz before trouble followed me home.

In early January, I boarded the train in Witten. I didn’t have to sneak on the train this time. Because my father was a senior employee at the Reichsbahn, I just went with him and he got me on, although that is all he could do for me.

“Willi, take care. If you explain why you are traveling alone, they will understand,”.

“Ok, Papa, I will”. It was awkward. I was not telling my dad what I expected was going to happen, instead agreeing with him I could just “explain” something to the Feldgendarmerie or the HJ guards, knowing all the while there was no explanation that would get me out of this mess without consequences. When I got home, I hadn’t exactly told my parents what happened on my way to Witten, so Papa still believed that I could travel as long as I had a valid ticket. I hadn’t had the heart to disabuse him from his belief that the only complication could arise from the fact that I was a minor traveling alone. But the problem wasn’t that I was traveling unaccompanied - the problem was that I was traveling at all. Papa meanwhile seemed to firmly believe in the common sense and reasonable nature of the authorities, who would surely see the logic in my arguments for traveling alone, and logic would prevail. It was disconcerting to me that I knew better. I had broken the rules and therefore I would inevitably be punished. But I didn’t want to worry him and it wasn’t my place to correct him, so I kept quiet.

Once on the train, I was on my own.

There was no lack of farm folk traveling by train, often with livestock, typically chickens or ducks in cages. As they didn’t seem to get scrutinized too carefully by the guards and they had helped me on the way to Witten, I went looking for farmers, hoping for the best. I was actually lucky enough to find another set of peasant women who were willing to hide me under their long skirts until I arrived in Konstanz. The compartment was shared by four women. They were friendly and talkative and asked me questions about my family. Maybe they thought of their own sons when they saw me and that is why they helped me. Maybe their sons were fighting at the front. How many husbands, brothers, sons had they lost? They couldn’t protect them, far out of their reach as they were, but perhaps they thought they could help me in a small way and that brought them some comfort.

As I sat under the voluminous long skirts once more, hiding out from the guards, I started thinking about the women’s sons, the brave soldiers who were risking their life to defend our country. They were heroes to me. They were keeping us safe against our enemies who wanted to kill us. I wanted to be brave like them.

The HJ guards and the Feldgendarmerie, carrying guns, were waiting on the platform as the train pulled up to the Konstanz station. I peeked out the window as it came to a halt and saw the officers checking every passenger’s credentials. There was no way I was getting off the train unnoticed.

“You, your name?” a Feldgendarmerie police officer, flanked by two HJ guards asked me as soon as I stepped out.

“Langbein” I managed to reply, sweating profusely despite the bitter winter cold. He glanced at a list in his hands, then nodded at the HJ guards. I froze in place. They grabbed me, handcuffed me and started walking, pushing me in front of them.

“Los, marsch, hurry up” barked the officer, poking my back with his gun. I tripped over my own feet because my knees had turned to pudding.

“Komm schon, lauf schneller, - come on, walk faster - ,”GET RID OF THE DASHES one of the HJ guards said sharply, hurrying me to the end of the platform along the wall of the building that spanned the entire length of the station. My head was screaming run as I stumbled along, my eyes darting around, hoping to catch somebody’s attention who could maybe help me. Nobody was looking my way. It was as if I were invisible.

“STOP,” came the sudden command. They opened a nondescript door and shoved me into what looked like an empty storage room somewhere in the back of the station. I was terrified. My throat was closed, I could not utter a single sound. They pushed me down hard into a little chair in the middle of the empty room and stood around me, not looking friendly at all. They started interrogating me.

“What did you do in Witten? Who did you talk to there?”

“My parents” I squeaked.

“Do you think we are fools? What were you really doing there?” their voices rose.

“It’s true, I swear,” I blurted out that my father was in the Party, and all kinds of other things.

“I don’t want to live with the Vollmar family, I want to be back with my parents. They relocated me here with the KLV, I don’t belong in Konstanz.”

They had to know that, but they just looked at each other with skeptical SCEPTICAL? expressions on their faces.

“How did you get on the train? Don’t you know it is forbidden for you to leave your host family? Is that how you show obedience to the Fuehrer? You’re a liar and a cheat, why should we believe anything you say?” Oone of the interrogators fired off the questions in rapid crescendo, getting louder and closer and closer to my face.

“I didn’t do anything wrong, I was just homesick. I am not a spy, I swear” I pleaded, and anything else I could think of saying to get me out of that pickle. Abruptly, without a word, they turned and left the room locking the door behind them, leaving me alone in there. I was panting. I had no idea what was going to happen next. Every minute seemed like an eternity.

What are they going to do to me? What if they don’t let me go? I just want to go home. I needed to go pee, I was cold, the circulation in my hands was getting cut off and my fingers were going numb. I started crying softly, which made the situation worse because I couldn’t wipe the snot off my nose.

Eventually, after what seemed forever to me, they came back. I vainly tried to read the expression on their faces.

“The Hitlerjugend Command has decided to let you go with only a light punishment this one time,” said one HJ guard standing in front of me in a wide-legged stance, his arms folded in front of him, while the other one undid my handcuffs. The Feldgendarme was not with them.

I breathed out, slightly encouraged by his words. I shook my hands, trying to restore circulation.

“As your punishment, you will clean the toilets at this train station for the next fourteen days. You are to report to the Station Master at 6:30AM tomorrow morning for your cleaning instructions. You can see yourself out now,.” COMMA the HJ guard said with a wolfish grin. My mouth gaped open. I heard a muffled guffaw coming from the other guard.

“Heil Hitler!” they commanded. I shot out of my seat. “Heil Hitler!” I croaked. They clicked their heels and turned to leave. I saw them elbowing each other on their way out. My shoulders slumped. I knew then that I was going to be the source of considerable amusement to the HJ organization for the next couple of weeks. They were going to have a good laugh on me, and there is nothing I could do about it, as much as I hated being the butt of their jokes. All things considered, I pondered as I walked out of the station, it had all been worth it to see my parents. I would still have done it even if I had known beforehand what the punishment was going to be.

The other thing I knew now was that it was no use trying to make myself scarce. There was no getting away. I was back with the Vollmar family for good.

“And that’s just one wartime Christmas I’ll never forget”

PS 1

Brian Moss news

You know, I’m sorry keeping you waiting for this news about the Brian Moss story. I knew I wanted to use the bomb disposal chapter in the podcast, so I contacted his son, Mike Moss, in Canada and he shared with me the absolutely fantastic news that he’s got a publishing deal, yet to be finalised but undoubtedly to be done. It’s unlikely the book is going to be out for quite a while because Mike is currently tying up a lot of loose ends. But having read the full memoir I think that’s really fantastic news. This man was dismantling bombs during the London Blitz, overcoming crucial anti-tank ditches in North Africa and wielding hand grenades on the D-Day beaches.

I’ll give you more information when I’m able but just remember, yet again, you heard it first on the fighting through podcast!

Here’s the last story for today.

Oh and don’t forget to download copies of all the old episodes when you get a chance. Some time next year a portion of them will go to paid subscription only. I’m sure you’ve got many months yet but just don’t forget.

I found this story on Wikimedia:

PS 2 – Christmas Truce ww2

In World War Two, there was no truce similar to the one that occurred during Christmas in 1914 in World War One. In that earlier conflict, thousands of British, French and German soldiers, exhausted by the unprecedented slaughter of the previous five months, left their trenches and met the enemy in No Man's Land, exchanging gifts, food and stories. Generals on both sides, determined to prevent fraternization in future, saw to it that such activities would be severely punished and so there were no more Christmas truces the rest of that war or the next.

But, in December of 1944, during the Battle of the Bulge, while the Americans fought for their lives against a massive German onslaught, a tiny shred of human decency happened on Christmas Eve.

MUSIC?

A German mother made it so.

Three American soldiers, one badly wounded, were lost in the snow-covered Ardennes Forest as they tried to find the American lines. They had been walking for three days while the sounds of battle echoed in the hills and valleys all around them. Then, on Christmas Eve, they came upon a small cabin in the woods.

Elisabeth Vincken and her 12-year-old son, Fritz, had been hoping her husband would arrive to spend Christmas with them, but it was now too late. The Vinckens had been bombed out of their home in Aachen, Germany and had managed to move into the hunting cabin in the Hurtgen Forest about four miles from Monschau near the Belgian border. Fritz's father stayed behind to work and visited them when he could. Their Christmas meal would now have to wait for his arrival. Elisabeth and Fritz were alone in the cabin.

SILENCE

There was a knock on the door. Elisabeth blew out the candles and opened the door to find two enemy American soldiers standing at the door and a third lying in the snow. Despite their rough appearance, they seemed hardly older than boys.

FADE IN AGAIN

They were armed and could have simply burst in, but they hadn't, so she invited them inside and they carried their wounded comrade into the warm cabin. Elisabeth didn't speak English and they didn't speak German, but they managed to communicate in broken French. Hearing their story and seeing their condition-- especially the wounded soldier-- Elisabeth started preparing a meal. She sent Fritz to get six potatoes and Hermann the rooster-- his stay of execution, delayed by her husband's absence, rescinded. Hermann's namesake was Hermann Goering, the Nazi leader, who Elisabeth didn't care much for.

While Hermann roasted, there was another knock on the door and Fritz went to open it, thinking there might be more lost Americans, but instead there were four armed German soldiers.

SILENCE

Knowing the penalty for harboring the enemy was execution, Elisabeth, white as a ghost, pushed past Fritz and stepped outside. There was a corporal and three very young soldiers, who wished her a Merry Christmas, but they were lost and hungry. Elisabeth told them they were welcome to come into the warmth and eat until the food was all gone, but that there were others inside who they would not consider friends.

The corporal asked sharply if there were Americans inside and she said there were three who were lost and cold like they were and one was wounded. The corporal stared hard at her until she said “Es ist Heiligabend und hier wird nicht geschossen.” “It is the Holy Night and there will be no shooting here.” [My edit: Pause, then, “Danke”]

FADE IN AGAIN

She insisted they leave their weapons outside. Dazed by these events, they slowly complied and Elisabeth went inside, demanding the same of the Americans. She took their weapons and stacked them outside next to the Germans'.

Understandably, there was a lot of fear and tension in the cabin as the Germans and Americans eyed each other warily, but the warmth and smell of roast Hermann and potatoes began to take the edge off. The Germans produced a bottle of wine and a loaf of bread. While Elisabeth tended to the cooking, one of the German soldiers, an ex-medical student, examined the wounded American. In English, he explained that the cold had prevented infection but he'd lost a lot of blood. He needed food and rest.

INSERT TUNE

By the time the meal was ready, the atmosphere was more relaxed. Two of the Germans were only sixteen; the corporal was 23. As Elisabeth said grace, Fritz noticed tears in the exhausted soldiers' eyes-- both German and American.

The truce lasted through the night and into the morning. Looking at the Americans' map, the corporal told them the best way to get back to their lines and provided them with a compass. When asked whether they should instead go to Monschau, the corporal shook his head and said it was now in German hands. Elisabeth returned all their weapons and the enemies shook hands and left, in opposite directions. Soon they were all out of sight; the truce was over.

Fritz and his parents survived the war. His mother and father passed away in the Sixties and by then he had gotten married and moved to Hawaii, where he opened Fritz's European Bakery in Kapalama, a neighborhood in Honolulu. For years he tried to locate any of the German or American soldiers without luck, hoping to corroborate the story and see how they had fared.

President Reagan heard of his story and referenced it in a 1985 speech he gave in Germany as an example of peace and reconciliation. But it wasn't until the television program Unsolved Mysteries broadcast the story in 1995, that it was discovered that a man living in a Frederick, Maryland nursing home had been telling the same story for years. Fritz flew to Frederick in January 1996 and met with Ralph Blank, one of the American soldiers who still had the German compass and map.

Ralph told Fritz “Your mother saved my life”. Fritz said the reunion was the high point of his life.

Fritz Vincken also managed to later contact one of the other Americans, but none of the Germans. Sadly, he died in on December 8, 2002, almost 58 years to the day of the Christmas truce. He was forever grateful that his mother got the recognition she deserved.

I’m Paul Cheall, saying,

I’ve gotta go now – I’ve got presents to wrap!

I’m going to play you out with a medley of Christmas tunes I’ve created just for the show …

Merry Christmas everybody

Featured Episodes

If you're going to binge, best start at No 1, Dunkirk, the most popular episode of all. Welcome! Paul.

PS. Just swipe left to browse if you're on mobile.