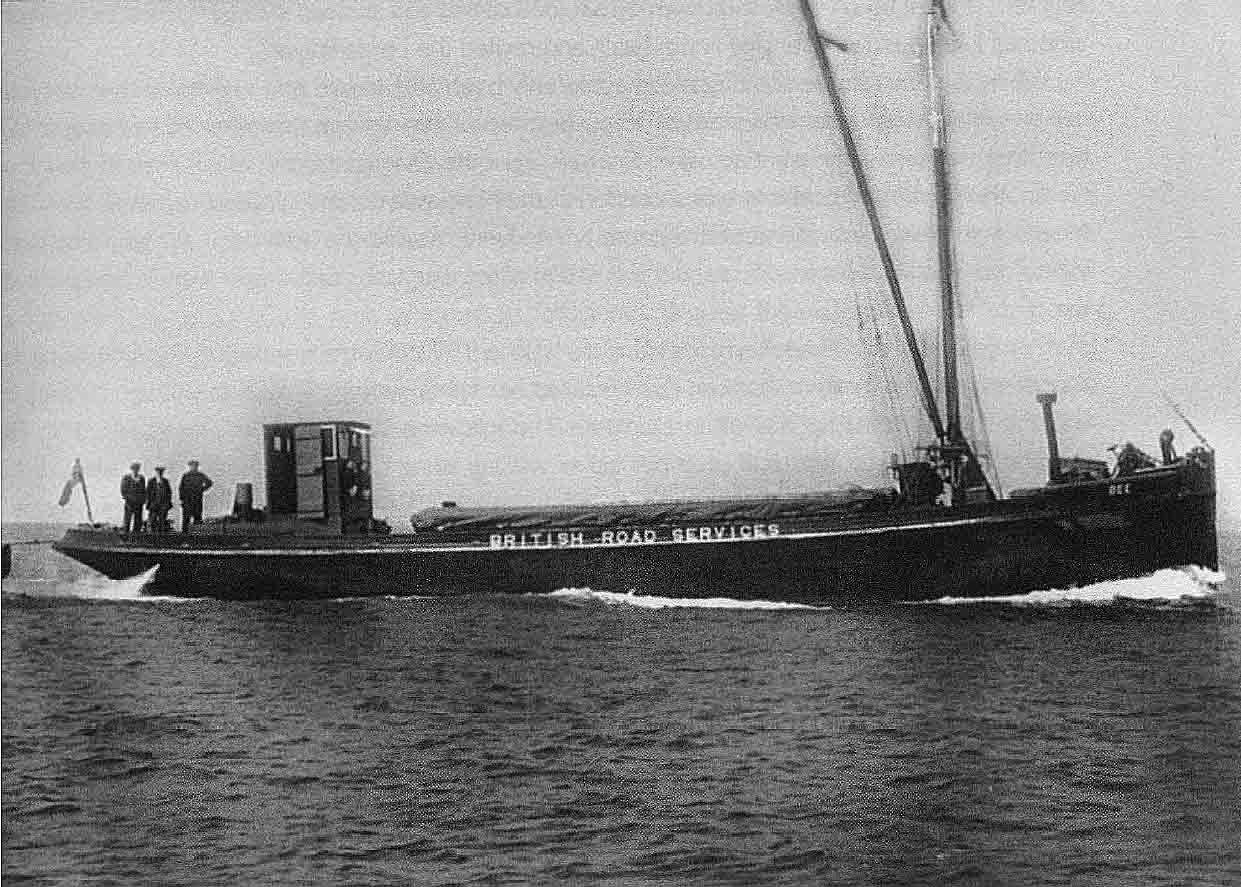

20 Dunkirk Little Ship Bee - UNABRIDGED EDITION WWII - Fred Reynard

COMPLETE and Original WWII memoir from Engineer of The Bee small ship

The scary story of the part some British merchant sailors played in rescuing allied troops from the beaches of Dunkirk.

"How welcome a sight as nine of our fighters arrived. Straight into the Huns they went and soon those Jerries were screaming towards the earth in flames, while the others streaked away as fast as their planes would carry them".

"A heavy bomb dropped near us and we shuddered badly. The next one I thought had us, for we went down with a wall of water towering above us on all sides" .

You may have already heard Episode 11, The Bee - this version is the much longer and complete version and is highly recommended.

Please take my MOBILE survey! I’d be grateful for any feedback on the Fighting Through Podcast, or even early comments on the survey itself. Replies are completely anonymous. Only 9 simple questions, so do please take a shufty! https://eu.jotform.com/build/202945895781067

More great unpublished history - of the Second World War.

Interested in Bill Cheall's book? Link here for more information.

Fighting Through from Dunkirk to Hamburg, hardback, paperback and Kindle etc.

FT podcast episode 20 – The story of little ship The Bee at Dunkirk – The complete, unabridged version – by Fred Reynard. WW2 and WWII

The following WWII memoir wasn't written by a professional historian.

It wasn't written by a retired military officer.

Nor was it written 50 years after events had taken place.

It was written by the engineer aboard one of the legendary little ships of Dunkirk. Fred Reynard hand wrote it in June 1940, literally weeks if not days after events had taken place.

There are no made up conversations nor any artificial dramatisation just to make it all interesting. This stuff is direct from the horse's mouth.

More great unpublished history!

How welcome a sight as nine of our fighters arrived. Straight into the Huns they went and soon those Jerries were screaming towards the earth in flames, while the others streaked away as fast as their planes would carry them.

A heavy bomb dropped near us and we shuddered badly. The next one I thought had us, for we went down with a wall of water towering above us on all sides.

I seemed powerless to move. I could only watch. Then one plane left the pack and came straight for us. I saw the four egg shaped bombs sailing, as it seemed, right on to us, then a deafening crash …

Troops were walking upright on the sinking ship’s side and a destroyer was alongside picking off all she could - and at the same time fighting off an aircraft which was doing its best to sink them both.

Hello again

I’m Paul Cheall, son of Bill Cheall whose WW2 memoirs have been published by Pen and Sword – in FTFDTH.

The aim of these podcasts is to give you the stories behind the story. You’ll hear memoirs and memories of veterans connected to Dad’s war in some way – and much more.

WWII Podcast Feedback

Before I proceed I’d like to share with you a little recent feedback about the show.

Witty Names from USA

I was driving across Montana and stopped to download a few new podcasts. I downloaded an episode of the show to try it out. When the episode I downloaded about the Bee was done, I raced the 2 hours’ drive to the next town so I could get an internet connection and download the rest of the show. Ever since then I’ve looked forward to new episodes.

Thanks for that Witty – but make sure you’re concentrating on your driving my friend or things mightn’t turn out to be so witty!

Ben Thomas UK

This WW2 podcast is absolutely brilliant. Some of the most poignant, heartstopping and thrilling World War 2 stories I've ever heard. Reminds me of many of the old fellas, (my grandad included) that I knew as a child

Andrew McLennan, Brisbane, Australia

As an Australian with a grandfather who fought in the Great War and also having completed a history degree at university, I have read a lot about the Gallipoli campaign. Your podcast on Gallipoli was excellent and filled in many gaps in my own understanding of certain battles and events (obviously in Australia we hear slot from the Anzac perspective and not as much from the British, French and Gurkha experiences.)

The diary you read from brought to life the horror and sheer hopelessness of the battles the Allies fought there.

Uncy.Pete from Australia

Wow this podcast is absolutely gripping. Hearing accounts from those that were there is amazing. Great work mate.

Thanks also to Shimi Lovat and Red Frostie from UK and Chuk Norris from Australia

WW1 WW2 Podcast apology

Now, I must apologise regarding an email address I’ve published in some episodes

Through no fault of my own, Yahoo have deemed fit to discontinue it and I can’t get it reinstated, so if you’ve written to me in the recent past at fightingthrough@yahoo.com and not had a reply then I’m very sorry but it’s because I’ve never received it.

In future, my correct email address will always be found on the contact page on my web site FTP.co.uk. I won’t publicise it in the podcast in case it changes again.

OK …

You may be wondering why a second Dunkirk little ship The Bee episode?

Well, unbeknown to me at the time, the first episode was an abridged version of a fuller memoir which only came to light when Fred Reynard's granddaughter, Helen, contacted me after the first episode was released.

Fred wasn't an ordinary civilian. He’d fought heroically in the bloody WWI battle of Gallipoli against the Turks in 1915. And of course two earlier episodes of this show are dedicated to his memories of that brutal battle.

So before you start this episode, listener, I’d strongly recommend you take in the Gallipoli episodes as well, for only by doing that can you truly understand who and what was this man who faced danger a second time by sailing to Dunkirk.

This man, who'd endured remorseless, heavy shelling and brutal hand to hand fighting against the Turkish soldiers of the Ottoman Empire.

How fortunate, serendipitous even, that someone with guts, determination and experience should be in a position to wage war again as a civilian - in rescuing the un-rescuable.

So, listen to Gallipoli and learn. Enjoy Dunkirk The Bee even more, knowing who that man was. It worked for me. WWII

INT

It so happened that we were discharging iron plates at Portsmouth Dockyard, when to our surprise a naval officer came aboard us.

“Leave your ship where she is when you’ve discharged, he said, “And make your way to your homes, as we require her.”

That seemed a tall tale, and to me a funny order, but we couldn't get any more information about it, so when we finished work, I went ashore to see what I could find out!

Through a chance word with the sentry I found myself before the Officer in Charge, Portsmouth Command, and he soon told me what we were wanted for:

“Your ship is required on a mission of danger and for that purpose I shall put naval personnel aboard.”

I asked whether there was a chance for us to go with her and he said there was no guarantee we would get back, although he didn’t say we wouldn’t get back.

Well, we won our case and a young Sub Lieut reported to the 'Bee' and with four days’ rations aboard, we steamed out of the harbour at 7.30pm.

We steamed through the night and all next day, and arrived off Ramsgate at 5.00pm where the commander went ashore for orders. He returned within the hour and then we knew our job:

“The BEF is being driven into the sea, and our job is to lift as many as possible from the beaches. It won't be nice you know, so if you want to change your mind, do so now, as I shall leave in one hour’s time.”

I said that we didn’t come to Ramsgate just to go home by train and what others could do – well, so could we. So, 7.30pm saw us enroute for Dunkirk.

Two routes were open to us, one via Calais where we could meet gun fire from the shore batteries for about three miles.

The other was to the North, a distance of 85 miles, where a German E boat was making itself a nuisance. The E boat's speed was the vital factor, so we decided on the Calais route, and moving as a lone wolf, arrived off Dunkirk at midnight and dropped anchor as per instructions.

Overhead was the drone of bombing machines en route for England. The sky was stabbed with dozens of pink searchlight beams, while everywhere around we could see the dark shadows of ships, both large and small riding at anchor, but we were unmolested.

In the distance one could hear the rumble of guns and the explosions of bombs and the fires raging in the town lit up the sky.

Dawn would break at 3.30am. We knew that was decided as zero hour. Sleep was out of the question, so we hung ropes over the side so as to help the men aboard when we started loading. Well, the dawn broke and our task was before us. We lifted the anchor and started towards the shore.

What a sight met our gaze. The sea was covered with oil and there was wreckage everywhere. The docks were burning, as were huge oil containers, and the town of Dunkirk was a pall of black smoke. The shores were black with human beings and there was a constant stream of men coming over the dunes down to the water's edge.

A rocket soared into the skies, a hostile signal our Lieut said. It wasn't long before over he came. A burst of machine gun fire hit the water near to us, but no bombs were dropped at us, but he let everything go on the lads ashore.

Well, if that was a challenge, then we accepted it and we were then all the more determined to get those lads off.

On we steamed towards the shore and the nearer we got the more destruction we saw, upturned craft, and the remains of human beings everywhere.

Medics were tending the wounded and doing what they could for them, but where could they take them? Only down to the sea, the only way out.

Back came the bombers and a near miss shook us badly. Warships opened up on them. A direct hit on a destroyer, and she listed heavily to port. Another destroyer loaded with troops was hit and was sinking.

Men swam towards the shore - some were picked up by smaller craft, but a large number, torn and mangled, went down with the ship. In less than an hour, we’d escaped destruction, but had seen death in the most brutal manner.

We were now nearing the beach and another near miss, one wondered if one’s luck could hold out. How welcome a sight as nine of our fighters arrived. Straight into the Huns they went and soon those Jerries were screaming towards the earth in flames, while the others streaked away as fast as their planes would carry them.

But our planes couldn't remain long, so back came Jerry and the bombing was resumed. Still, that unceasing trek by thousands of wary men continued down to the sea. Cars, lorries, motor cycles and all military equipment was being driven into the water or destroyed.

A lone chestnut horse trotted up and down the shore, an unknown fate in store for him. More of our planes arrived, and one crashed on to the beach. With more of our planes, what a different story I could relate.

We drove full speed on to the shore and ground but they came towards us, some wading almost to their necks in the water, those men of the BEF.

We soon realized that the ropes we put over our sides were useless, for with the extra weight of water and exhaustion - and there were some with wounds - it was impossible for them to climb on board.

I quickly sawed our long ladder into two halves and hung them over the bow of our ship, and this proved just the thing, and the loading began.

Up those ladders those lads came. Tall, short, thin and fat. Men from the Highlands, Midlands, North and South of England. Some wounded, some with equipment, others without - but all with the determination to live.

We were doing fine, then the bombers came again. The troops dispersed and they swept the shore again. We escaped again but a hundred yards down the beach he took a terrible toll of life and little ships.

WW2 podcast contd

Another start and with a few more interruptions, we filled to capacity. Every spot where a man could stand was filled, both down the hold and on the desk.

Then our first big problem confronted us, that was getting off the beach. For over an hour we tried without success, then our trouble was spotted, and a French tug dragged us off free.

But we were not for England this time for no sooner had we got on course than the order came to transfer troops to a ship of a longer draft and then to carry on as before.

Well, orders were orders so we proceeded to a French sloop a half a mile offshore and transferred our load 375 men in all. We started off to the beaches again, with the same system of loading in mind, but things were beginning to take a different course.

The heavy bombing on the water’s edge had made large craters and being just covered with water made it dangerous to ground, for with the tide leaving - a ship like ours could break her back.

The wind had come on as well, and a ground swell was running, which didn’t help matters, so there was nothing for it, but to drop anchor as close as we dare to the shore and load with our small boat. We had about twenty men aboard and he came again. The 'Gracie Fields' was hit on her quarter and they got her in tow but she sank.

A heavy bomb dropped near us and we shuddered badly. The next one I thought had us, for we went down with a wall of water towering above us on all sides.

WWII podcast contd

Then the old lady shot upwards to the surface, giving us the sensation of coming up a lift. I didn’t enjoy that. A small launch passing us was hit, and a heap of timber fell on us from her. One minute 16 men alive and well - yet within seconds nothing to show that they ever existed except the water stained with blood. The hell of war.

Two Dutch cargo boats were doing good work loading with naval launches from the shore. They were under the White Ensign and didn’t those jack tars work.

Now the tug 'Foremost' left the only pier usable with a large lighter of ammunition in tow Bombs dropped close to her, but her master didn’t alter course one degree, and one could only admire him for his superb courage.

I shudder to think what would have happened to us and to a large number of ships had she been hit. Our progress of loading was much slower now, and tiring, but we were spotted and a naval launch joined us and began to ferry to us from the shore.

After three runs of 17 men a time, she was caught broadside and capsized and although all were picked up, that finished our extra ferry. Our numbers steadily mounted and he still raided; five of our fighters arrived and there was a good dog fight overhead.

He dropped everything and some, but there were plenty under when those bombs fell. Heaven knows how many mothers' sons were blown to eternity in those few moments, but again we were lucky.

Things seemed to be stepping up more now for the raids were more frequent and the whine of a shell or two told us he was getting nearer to coast.

But I was sure everyone was doing their very best and one could do no more than that. The weather was hot, and events even hotter, but strangely enough neither thirst or hunger bothered us.

One was struck by the calm bearing of those aboard us. Whatever happened, they took it in their stride. I hoped they would get safely home.

Still that steady stream of men made their way down to the shore, stopping only to fire at the raiders or when death lay them low.

WW2 podcast contd

The hospital ship 'St Julian' came into the pier and started the evacuation of the badly wounded. A shell dropped close to her, but she wasn’t bombed. The day wore on and one lost all sense of time.

We found ourselves with another 310 aboard. These we transferred to a small coaster and her load then complete, she sailed for home and right glad they were. We settled down to load again. Evening drew on and more ships began to arrive and among them I found quite a number of French and Belgian fishing craft.

The shelling increased but the raids became less frequent. The 'St Julian' left and her place was taken by the 'Lady of Mann' also to load wounded. But she was not so fortunate for he did bomb and damage her a little.

When darkness fell a little after 11pm we had about 100 men aboard. It was a slow process loading now for we were all beginning to feel the strain of heat, and long hours, but one must keep on while there were men to be lifted. He raided offshore during the hours of darkness using flares but he didn't come too near to us, for which we were thankful. During the four and a half hours of darkness, we took on about one hundred and thirty.

Many of these lads seemed in very bad shape - tired and hungry and they told of insults from the French and roads packed with men women and children - and they were glad to be on a ship.

The dawn of another day broke. Three thirty a.m. the first of June. The glory of June they say, but what did it hold for us? We saw the dawn, but would we see its dusk?

One thing was certain - there were hundreds of men on those shores and on the boats who would never see the close of this day. That was fate and we had no right to expect to be favoured than another person.

We were weary but we carried on still adding slowly to our numbers. The ever increasing light saw the S.S. Scotia loading French troops at the pier, the 'Lady of Mann' having left during the hours of darkness. And the Ryde to Portsmouth paddle steamer 'Whippingham' was also getting a large number of British troops from the pier

WWII podcast contd

The destroyers have had good hauls during the night, and were leaving for home, as were scores of small craft with their tens and twenties. Other destroyers were arriving and let go their anchor offshore.

He saw the movements and started heavy shelling and seemed to be getting the range more accurate. The morning took shape and the Scotia left with over 2000 men from France.

The Whippingham also left with her sponsons awash with approx. 2000 aboard. The S.S. Scotia was a double funnelled cross-channel boat and very fast.

We watched them clear the harbour and carried on loading again. Then things began to happen. The sun seemed to darken as shadows came over the hills towards the shores. What was about to happen?

We all looked to the sky. He had come before in 15s and 20s but this time - well - formations of 50 or more came over, wave after wave of bombing planes screamed out of the sky. The noise was really frightening as they dived down to the sea.

It seemed as if he was determined to end it all, and blow everything off the earth and sea. That next hour at Dunkirk will always be with me, if I live to a hundred years. Hell can have no comparison to that unleashed fury.

Destroyers twisted and turned in an effort to escape the screaming bombs he threw at them. A destroyer was hit and steamed round in circles as if her steering was damaged. Another was badly damaged. Tugs took her in tow. But the tow wire was cut with another stick of bombs.

Yet another destroyer was hit and a large tug rushed to her, then the tug received a direct hit and went down with all hands.

The minesweeper 'Skipjack' with 270 troops on board was sunk with all hands. They must have perished like rats in a trap.

A French destroyer stopped a stick of bombs and turned turtle. Men were swimming everywhere. The planes dived to sea level. A burst of machine gun fire crashed into the upright on our wheelhouse. A bomb splinter tore a hole in our sail aft. A soldier's face was split open full length.

WW2 podcast contd

Another explosion rolled us on our beam end everyone hung on like grim death. The rush of air from another bomb almost choked us as it seemed to draw all the air from our lungs. The paddle wheel minesweeper 'Brighton Queen' steamed past us making for the open sea. She was loaded with black French troops and packed like sardines. A plane dived straight for her and the bombs landed right in the middle of her troops aft.

Men went into the air like a cascade of lava and limbs and bodies hit the water close to us while some of our lads were splashed with brains and blood. The sea ran red for a while and seemed to boil with explosions.

We rolled and tumbled on the disturbed waters. A ship was hit, now a miss - the noise, the cries, men jumped free as their ship foundered, yes into water thick with oil. I watched with others expecting my turn. How can he miss - he is bombing to a pattern!

Another near miss, and we nearly capsized. Those Stuka pilots were past masters at their game. We saw them sitting in their machines as they swooped past us. A terrible toll in ships and in life. The destroyers were fighting back with all they had. One had to admire the cool way the officers directed the fire. They blew hell out of him as he dived and more than one Jerry made his last raid that morning.

Explosion followed explosion as a ship was hit, the noise of battle was truly on, one could scarcely hear one speak.

Wave after wave they came, sometimes along the shore, and sometimes further out to sea. Ships were set on fire, small craft blown into the air men maimed and torn, blown into the sea with them. One was helpless, one just had to wait, hope and pray.

The destroyer 'Esk' was warming him up, the officers cooly conducting operations from the bridge. How proud I felt at that moment to belong to the same race. Then we had a breathing space, a welcome respite.

The planes went and we had time to look around. Our young officer caught my eye and he beckoned me. I never saw a man so cool and composed and he just said to me "Spiteful swine, the Boche, Fred" and I could not have agreed with him more.

He then pointed to a destroyer which was about to take the final plunge. As her ensign disappeared beneath the sea, he came smartly to the salute. She had gone to her grave, taking some of her gallant crew with her. I watched with him and removed my cap, and paid my solemn tribute.

Such was the tradition of the British Navy. Such was the tradition that enabled those lads to endure. The little fleet of French and Belgian boats had been almost wiped out. There seemed but one that was not either sunk or in flames.

We tried to reconstruct. Four British destroyers had gone down plus one French destroyer. A British sloop, two minesweepers, scores of tugs large and small and dozens of small craft had been blown up and in addition three destroyers and a score of other craft badly damaged.

And the men ashore – they’d taken a severe pounding. Bombed shelled and machine gunned no one will ever know to what extent they suffered that day for the remains of some will never be found.

What a sight confronted us, crippled ships, broken spars, maimed men, oil and wreckage everywhere. The cries of the wounded and the appeals of the drowning made me feel ill.

Small boats still afloat were picking up all they could - a very difficult job. Men slipped back into the water and drowned, when help seemed near them. Choked with thick black oil, they had a terrible death.

The bombers came again, but went further out to sea. It mattered little to us, then, for we were all beyond caring. But why had they come so near without destroying us?

Was it fate, or luck or was it the answers to the lad who knelt at my engine room hatch and said the Lord's Prayer finishing with the words 'Deliver us from evil'. It was times like these that made men think. This was indeed a tragic day for the Royal Navy and those who survived were like us, fortunate.

We resumed loading, for movement on the beaches had begun again. A very slow process now, dog tired, but determined. A fast launch with a high ranking naval officer was getting in touch with the little craft further up the beach and some were moving out to sea.

Now a convoy of lorries arrived from somewhere and was being driven into the sea end-on to form a pier as the tide came in.

WWII/WW2 podcast contd

Then we got a message "Clear out what you have and proceed to Ramsgate - Route Y". We knew what that meant - the other passage was strewn with magnetic mines, and to us that was not a happy thought us being a steel ship. Well orders were orders and with 291 aboard we prepared to leave.

It may seem selfish when I say that I was not sorry to hear that order, but with men still on the shore, we nearly refused to carry out those orders. We were in it with those lads and we had room for a few more but someone had to be in charge and therefore we must leave.

But lack of rest food drink and the continued bombing was beginning to have a marked effect upon us all. There was a limit even to our endurance, for we were only human beings. We steamed slowly out and into the channel.

The large oil containers were still belching out their large columns of smoke and the hospital ship 'Paris' was just arriving. I looked to the wounds of a soldier's leg and whilst engaged looked up into the sky. Coming straight after us were 20 dive bombers.

Is this the end I thought. It might have been fear, I don’t know, but standing near my engine room hatch I seemed powerless to move. I could only watch. Then one left the pack and came straight for us. I saw the four egg shaped bombs sailing as it seemed right on to us, then a deafening crash and they landed about 25 yards away.

The old ship twisted and rolled and water came aboard us but the depth of water had saved us for had we been in the shallows, we should most likely have been holed.

We steamed slowly on because of the wreckage and what a sight of destruction it was. The remains of once fine ships were everywhere as were the remains of humans. Masts and spurs just showing out of the water told the size of the ship sunk. It was a pitiful sight.

As we cleared the harbour we saw another tragic sight. We had seen the S.S. Scotia with over 2000 French troops about to leave just prior to the raid, and we saw her now. She had been hit and was on her beam end with her funnel nearly level with the water.

Troops were walking upright on her side and a destroyer was alongside picking off all she could and at the same time fighting off an aircraft which was doing its best to sink them both.

WWII/WW2 podcast contd

Ahead of us we saw a ship’s lifeboat and proceeded to it. Huddled up on the bottom were five French soldiers. We took them aboard, for they were in bad shape and we got them round. One spoke good English having once worked at the 'Ocean Hotel' at Sandown. He said they were escaping and were caught up in the raids and had laid flat hoping for the best.

He saw the French destroyer sink and said her name was the 'Foudrayant' and he said the crew sang in the water but that to me didn't seem right. One of our destroyers sunk was H.M.S. Keith and he said a number of her crew was picked up.

We steamed south a little for there was less traffic that way. Soon we passed over the grave of an unknown ship. Thick patches of black oil coming to the surface marked the spot where she rested.

Among the wreckage was a number of sailors' hats, the ribbons bearing first three letters H.M.S. Face downward in the black oil. And their bodies supported with their life jackets were some of the sons of Britain who had served in her.

We clipped our little red ensign as our mark of respect and steamed on. A mist was beginning to come down over the Channel and the sound of battle more distant. I went into the wheel house and looked down on those lads those part remnants of the B.E.F. Weary, tired, bedraggled and unshaven, hungry and thirsty, they were a sorry sight.

We had nothing to offer them and because of that we had nothing ourselves. Nothing had passed my lips since we went to the beaches the previous morning, and they were stuck together as if with gum.

Some slept as they stood, others cursed as a shell from Calais exploded. Some swore and some prayed. I heard a voice singing the hymn 'Though the night of doubt and sorrow' and I wondered, “Did the author of that hymn ever visualize a Dunkirk?” For those lads had passed through nights of doubt and sorrow - but they had come on, as a band of brothers, the stronger - taking the arm of the weaker down to the shore, and the promised land of Britain.

We reached Ramsgate and tied up at the outer mole. We’d steamed into hell and had returned safely and we were thankful for our deliverance.

A soldier came up to me with tears in his eyes. As he shook my hand he said 'Thanks old man'. I never thought I would see my wife and kiddies again. Those simple words, sincere as they were spoken, had for me made the journey worthwhile.

I watched those lads stagger up the gangway.

As on the beaches, the stronger helped the weaker and those with wounds.. Red Cross personnel took charge of the wounded and hurried them away. And ladies with cups of tea, cigs and cakes attended the needs of the fit.

We steamed into the Inner Harbour and moored up and the bells rang 'finished with engines'. I closed down, sat down and fell fast asleep.

…

I’ve tried to relate some of the major happenings which befell us, as the crew of the Motor Vessel Bee on our little trip to France.

There are many incidents of heroism and self-sacrifice I could recall had I the time, acts equal to many which had brought honour on the battlefield.

There was the man who through exhaustion fell from the ladder and was almost drowned and there was the man who saved him and by so doing lost his own chance to be taken off.

The wounded man who carried his wounded comrade down to the water's edge and then fell dead.

The man who knelt in prayer at my engine room hatch and the man who shouted in defiance as we left the beaches. 'Make the most of it Jerry - because we will be back!'

This was typical of the men we helped and these were the men we were proud to have saved. When I first looked into Dunkirk on the early dawn of that late May morning. When I saw the burning town, the blazing oil tanks, the damaged wharfs and docks and the men in thousands on the beaches, and streaming over the dunes down to the shore I thought we had an impossible task. WWII/WW2 podcast contd

But when he awakened us from our dreams with that first burst of machine gun fire, and when we saw those lads, those sons of mothers of our own country, being bombed and slaughtered like cattle, then we were determined come what may to bring them off - or stay forever with them.

Dunkirk will be rebuilt in the years to come, the wharfs and docks will again house the liners of the seven seas. The tides will still flow over those same beaches but the stains of blood left there by the B.E.F. will never be erased. The little ship that stood us in such good stead during those hectic days will again make her way between the Island and the mainland ports.

To those who see her pass she will be just a little ship, but to us who knew her she is a symbol - a symbol expressed in just one little word - Dunkirk.

My story of Dunkirk is finished but the real story can have no end, for those who could complete it lie buried on the shores of France or beneath her seas in the ships they served so well.

- Reynard

June 1940

Listener, I’ve posted up the full text for this podcast on my web site FTP.co.uk. Here you’ll always find show notes, photos, links, subscribe buttons, feedback, social media and contact buttons – everything you might need, so please take a visit.

You’ll also find full details of my Dad’s book, Fighting Through from Dunkirk to Hamburg – published by Pen and Sword – Of course this book is what inspired the show and there are some great deals available in both hardback and electronic form. And with over 100 Five star reviews on Amazon it’ll make a great present for anyone interested in military history! WWII/WW2 podcast contd

All of the above are at FTP.co.uk.

And if you have a war memoir you think you’d like to hear on the show, please get in touch. I’d be delighted to help however I can.

Next episodes:

A while back I was interviewed by Angus Wallace of the WW2 Podcast. Angus’s show revolves around interviewing people who’ve had military books published and looks at many aspects of WWII and military history so I feel very honoured that he asked me to talk about Dad’s memoirs – so if you’re after an insight into Angus’ excellent show and Dad’s book, please listen in to episode 21.

In Episode 22, I’m looking forward to another coffee with army veteran Wilf Shaw whom you may from episode 4 of the show. I’ve since met up with Wilf several more times so my next episode is dedicated to one such encounter and we’ll be regaled with more tales of fun and daring do in his continuing service with the Green Howards and Montgomery’s Eighth Army.

PS:

This is a letter to Fred from one of the few people outside the family who actually got to read Fred’s memoir.

Dear Mr Reynard

I have read your first-hand accounts of those two shocking episodes in our country’s military history – Gallipoli and Dunkirk – and found them very interesting.

Having joined the Royal Flying Corps at the age of 16 and carried on in the RAF until after the second world war, I know how much official records compiled by brass-hats differ from the stories of the men who actually bore the brunt of warfare …

… and not infrequently suffered in operations planned from a distance by people with no knowledge of the conditions existing on the spot. Lives are cheap in wartime.

Unfortunately, very few of those who served in the ranks ever bothered to commit their experiences to paper and their sacrifices and hardships go unrecorded. Thank you for the opportunity of reading them.

We grow fewer as the years roll by and must consider ourselves lucky indeed to live to recall those days and the splendid fellows with whom we shared them – many, alas, unable to do so.

Best wishes

Yours sincerely

S E Townson, W/Cdr RAF Ret’d

PS I too have recorded my recollections of 30 years spent on the company of the same breed of men at home and abroad, in peace and war, and they brought rewarding memories.

ends

http://fightingthroughpodcast.co.uk/periscope/4592998477

Featured Episodes

If you're going to binge, best start at No 1, Dunkirk, the most popular episode of all. Welcome! Paul.

PS. Just swipe left to browse if you're on mobile.