48 Captain H E Hovell - First World War

Memoir from a Norfolk, UK, man who fought in both World Wars

A wonderful memoir from a Norfolk man who fought in both World Wars. The story has a real Enid Blyton famous five adventure flavour to it. It’s dripping in rich pre-wartime history and beyond.

"We were sent down to the French Experimental Station. The French released the gas and we were placed at various distances wearing respirators. We had dogs with us. We also had to go in these large glass chambers, until we found the gas coming through.

"In about two weeks we again went up the line in the trenches at Vimy Ridge. We prepared our emplacement for a raid by the Canadians to capture prisoners to gain information for the big attack that was to come. It was intended that we’d fire gas shells during the early hours followed by smoke to give the Canadians cover.

"We went up the line in the trenches at Vimy Ridge. We prepared our emplacement for a raid by the Canadians, to capture prisoners to gain information for the big attack that was to come. We were to fire gas shells during the early hours, followed by smoke, to give the Canadians cover.

"I was first in line but I had to stop for a few moments to feel for my boot in the mud, empty the mud out, and put it on again. I lost my place so then I was ninth in line. Then Jerry dropped a shell right in front of the line ...

Slang words used in the episode:

Fourpenny one – A punch

Sweat – soldier

Warned – told to get ready for action

Get cracking – Get lost, go away.

Midden – dung or refuse heap

Feedback/reviews in Apple Podcasts - Thank you.

The early scout patrol group

It was the winter of 1908 before we met any more scouts or even heard of them. One cold afternoon we were on the road towards Swardeston when we came across some more partly-uniformed scouts. In our meeting was my friend Cook. I had met some of the others before, they included the Kirby brothers, Tapscott, Bobby Murihead whose father was choir master at Holy Trinity Church, Norwich. (Photo yet to be traced)

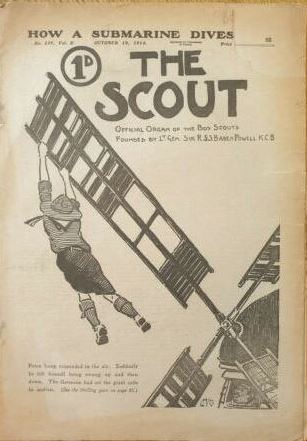

The Scout Magazine

https://www.sciencehistory.org/distillations/a-brief-history-of-chemical-war

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/World_War_I

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Vimy_Ridge

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gaymer_Cider_Company

https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/m0008zvf

Interested in Bill Cheall's book? Link here for more information.

Fighting Through from Dunkirk to Hamburg, hardback, paperback and Kindle etc.

Capt H E Hovell

Born 14 November 1893, died 8 November 1978. The memoirs where written round about the early seventies.

"We eventually heard during the spring of 1909 that a Mr. Barnes had formed a small troop of scouts, we paid him a visit and soon after joined up with him. He had a shop in Exchange Street Norwich where he sold garden tools, raffia, bass etc. He was a tall solid man, walked with a long stride, wore corduroy breaches, and buskins (leggings). We held meetings at his shop and carried on scouting under his guidance for some months. Then it became known that a Mr. Claude Stratford had been appointed local organiser and later, I think direct commissioner.

We had a large rally when King Edward VII came to Norwich, I believe to lay the foundation stone for a new wing at the Norfolk and Norwich Hospital.

We formed up in the grounds of the local Y.M.C.A. prior to lining the route I think near Ketts Hill.

The illustration shows us formed up ready to leave the Y.M.C.A. Mr. Stratford in front, Mr Barnes at the extreme left, myself fourth from the left in front rank, the extreme right is a Mr. Hamilton."

First World War

Second World War - possibly now a Major?

Not sure about this pic

Poem from the memoir

I knew a man of industree

Who made large bombs for the R.F.C.

He pocketed lots of L.S.D.

And then they made him an O.B.E.

I knew a woman of pedigree

Who asked some soldiers out to tea

She said "Dear me" and "Yes I see"

And she they made an O.B.E.

I knew a man of twenty-three

Who got a job as a fat M.P.

Not caring much for the Infantree

And he also was made an O.B.E.

I knew a lady fair to see

Who put rolls of paper in the W.C.

And soap and towels in the lavatree

And she too they made an O.B.E.

I had a friend - a friend, and he

Just held the line for you and me

And kept the Germans from the sea

And died without the O.B.E.

Yes he died "without" the O.B.E.

Fighting Through Podcast - Episode 48 - Captain Harold Edward Hovell WW1

First World War

More great unpublished world war I history!

Hello again and a warm WW1 welcome to you, as it is World War One this time! OMG!

I’m Paul Cheall, son of Bill Cheall, whose second world war memoirs have been published by Pen and Sword – in FTFDTH. The aim of these podcasts is to give you the stories behind the story. You’ll hear first-hand memoirs and memories of veterans connected to Dad’s war in some way – and much more. And the ‘much more’ this time happens to be a totally original unpublished first world war history written by the late Captain Harold Edward Hovell. More on that shortly.

I haven’t mentioned the FT website in a while so just a gentle reminder that whenever I refer to the show notes then you will find them at fighting through podcast.co.uk. There are some show notes on your listening app where it caters for them but if you want the full monty then go to the web site.

At the website you'll also find links to buying dad's book, FTFDTH. Since the last episode half a dozen of you have taken advantage of my recommendation to buy the book through the Amazon link and as a result you got not only a signed copy but a special souvenir fighting through bookmark as well as a couple of photographs, my signature, a smile and eternal thanks.

On the Amazon list look for the copy being sold by me to get the extras, and I can ship worldwide. If you’ve already bought the book - thank you - just drop me an email if you’d like a free bookmark and photos. All contact through FT Podcast.co.uk

Today I’m bringing you a wonderful part one of a memoir from a Norfolk man who fought in both World Wars. The start of the story has a real Enid Blyton famous five adventure flavour to it. And it’s dripping in rich pre-wartime history and beyond.

You’ve just heard a few short clips from this man’s writings and there’s much more to come.

First, some Feedback and Families stuff …

On the last episode, when I tortured you all with my German pronunciation, I shared some negative feedback with you and also some positive feedback from Wolfie wolf.

Well, Wolfie it occurred to me after the episode that that I should really have referred to you as Volfie given that it was a German episode and the Germans always pronounce a w as a v.

Does anyone know that a VW car is pronounced FV in German?

Regardless, Volfie, you kindly posted some feedback in Apple podcasts.

“Thanks for reading my review on your podcast. First time I ever heard back from the many podcasts I’ve given reviews to. About the other guy’s bad review. Don’t worry too much about it. I really enjoy your podcast and I always look forward to your next one...

volfie/volf via Apple Podcasts · USA

Very Vell, Volfie – thanks so much for that – you helped make my day so much better. I should add that I always try to respond to everyone who contacts me and I also work with everyone who sends memoirs in to get them in the show, so no-one should hold back thinking their stuff will go into a bottomless pit never to be seen again. Now for a bit more on the German language and a bit of mickey taking …

Nicht Sheesen!

Nicht schießen – Nicht Sheesen – Don’t shoot

Nicht scheißen = Nicht Shysen – Don’t crap!

I’m normally quite proud of my German pronunciation and although I’m sure I don’t get it right every time, the following comment from Ruud Schermer certainly brought me down to earth with a bump. He’s has pointed out an absolute howler that I committed in episode 48 German Eyes when I read from Jon Trigg’s book.

So although I was bursting with pride as I got my tongue and tonsils round the Olympic gold medal-winning, Knight’s cross-wearing panzer commander Hermann Leopold August von Oppeln Bronikowski …

Even though I was chuffed to bits as I hacked and spat my way valiantly through Widerstandnest and Panzerjager Abteilung

And I thought I’d totally triumphed with Von Schlieben, Oberfeldwebel and Nicht Sheissen!

Until …

Ruud playfully observed in Twitter … “Just one remark (sorry). At some point the story goes about surrendering German soldiers, saying something like "Nicht schießen" etc. The way you read it out had me in stitches.

Listener, anyone who knows the slightest bit of German will already have sussed where Ruud is going.

But just in case the penny hasn’t dropped yet, I’ll elaborate:

The Americans are running up Omaha Beach, and they're attacking a pillbox, or something. Some Germans run out with their hands in the air pleading not to be shot. Old clever clogs, here, with his fancy German pronunciation, trots off the sentence from the book and says “Nicht Shysen!” Of course, what I should have said was “Nicht scheesen!” Now, one of these phrases means Don’t shoot, The other means, if you hadn’t guessed “Don’t … well .. I think you can guess! And obviously I got it wrong. But in truth the Germans probably were Shysing themselves so maybe I got it right in the first place, who knows!?

I think it’s hilarious how in both languages the changing round of just one or two letters makes such a big difference to the meaning of a word.

From now on I’m going to stick with “For you Tommy ze var is over” and Volfie Volf.

So thanks Ruud. I think that almost beats veteran Wilf Shaw’s joke about Oldham football club, though not quite. If you’ve not heard Wilf’s story about his favourite soccer club then listen in on my special anniversary Episode 50, when no doubt I’ll be repeating it along with a few more old but favourite stories, along with some new ones too.

Tori from USA wrote in:

Thank you so much for creating this podcast and continuing it for so long! I'm on episode seven about Sgt. Douglas Gray in Normandy. This is really just fantastic to listen to and I can't hardly wait each morning after I drop my son off at day care to listen on my hour drive to work!

One thing that really stuck out to me, was veteran Wilf Shaw. He sounded incredibly similar to my grandpa, Rocky, who passed away last year in May. He also fought in Western Europe and it made me slightly emotional hearing Wilf’s stories, but with a bit of a comical tune - just how my grandpa would tell them.

He would also say he wasn't sure if it was worth it, and we had many talks about that.

I was saddened last night reading through the posts on the website, seeing that Wilf had passed just a couple months before my own grandpa. What a character! I've always been fascinated by the folks of that generation, telling you about the heartache like it was just another day. I don't think I would've been able to cope the same if the war I had been in were fought like theirs. Unbelievable.

I am so grateful you are sharing these stories of the Greatest Generation. Their voices are quickly becoming only memories and it is a wonderful tribute and honor to them to have their words shared.

Sincerely and all the best,

Tori from Maryland USA

Tori - Many thanks for all that and it is quite amazing how all these characters contributed to our freedoms today. I couldn't help remarking on the fact that not only have you got a young son to look after, but you have to drive for an hour to get to work and an hour to get back and yet you still find time to listen to the fighting through podcast and even took the trouble to write in.

I realise you listen to the show in the car but you're clearly a lady who has got her stuff seriously together - and I think for that you thoroughly and absolutely deserve this month's fighting through podcast How Good is That? award! [Applause] – maybe Rufty’s Riff?]

So sincerely well done Tori and thanks again for your sentiments and support.

War Stuff

Last episode I told you about the World on Fire TV series and I’ve just watched episode five of about Dunkirk. And wow, some great sequences of Stukas flying over the beaches, I suspect they weren’t real but they looked real enough and gave a very dramatic insight into what the scenes must have been like. So listener, miss this series of ordinary and not so ordinary lives in second world war Europe and regret it. It’s on BBC 1 where you can get it. World on Fire. Link.

I’m very grateful to Virginia Dack for giving me access to her late father's memoirs. He was Captain Harold Edward Hovell, who fought in two world wars.

The memoir has a real Real Enid Blyton famous five adventure flavour to it. It’s dripping in rich pre-wartime history and beyond. It’s an original WW1 account written by a man from Norfolk, England.

Coincidentally, it’s Norfolk where I live, and if you’ve listened to other episodes you’ll know it’s where I once saw the freshly harvested mint crop being collected by a bright yellow Colman’s harvester, and where my army socks nearly got blown off with fright when I was confronted by a Jack Rabbit when I was on my bike one day.

And if you want to check out Norfolk on the map, then it's the great big bit that sticks out above London on the East Coast . It’s populated a little more thinly than many areas in England and has quite a lot of waterways, called the Norfolk Broads. And there's lots of flat countryside!

And of course The United States 8th Air Force, The Mighty Eighth, brought attention to the area when they arrived in Norfolk in 1942. And throughout the rest of the war there were around 50,000 US personnel stationed within a 30-mile radius of capital city Norwich.

This story starts off with the writer as a young man, in 1908, covering his early life as one of the very first boy scouts, moving on to the drama of the First World War and ending with an insight into his early years following the war.

It’s almost breath-taking what the young boys achieved in the Scouts compared with what boys seem to do these days. But what they did get up to in the countryside was clearly preparing them for War! And there are some surpising first-hand accounts of significant historical events which to us seem like ancient history but which this man lived through.

We’re also going to hear about the famous world war one battle of Vimy Ridge together with some quite awful revelations about the use of gas by both sides.

Backstory to WW1

World War I also known as the Great War, was a global war originating in Europe that lasted from 28 July 1914 to 11 November 1918. Known as "the war to end all wars" involved over 70 million military personnel, making it one of the largest wars in history. It is also one of the deadliest conflicts in history, with an estimated nine million combatants and seven million civilian deaths as a direct result of the war. On top of that there were genocides and the resulting 1918 influenza pandemic caused another 50 to 100 million deaths worldwide.

The war involved 32 countries. The Allies included Britain, France, Russia, Italy and the United States amongst others. These countries fought, mostly in Europe, against what were called the Central Powers which included Germany, Austria-Hungary, Ottoman Empire and Bulgaria. There’s plenty of online resources if you want to explore all that further including Wikipedia.

Gases

I do want to mention the gases which were used in this war because they feature a lot in this memoir.

Three substances were responsible for most chemical-weapons injuries and deaths during World War I: chlorine, phosgene, and mustard gas. Collectively, they would irritate the organs and senses which affected sight and breathing.

So when you see these old war photos of soldiers being led in a line blindfold, they’re probably suffering from gas.

Hundreds of thousands of soldiers were killed or incapacitated by these gases and if you want to learn more about the unsavoury, revolting effects of these gases, there’s a link ..

My own Grandad Arthur Warren, fought in the First World War and I remember as a child he was always coughing and wheezing with a very bad chest. He said he'd been gassed at the Somme. And this would have been maybe 50 years after the war had ended so it affected him for the rest of his life. I can remember him now, taking me to the local park to play on the swings. And we’d stop off at a shop where he’d get some mint imperials to suck on. And I’d be trotting alongside him playing with a toy car he’d bought me while he sucked and wheezed his way through his sweets. Every now and then today I do buy some mint imperials and I remember my grandad.

The Battle of Vimy Ridge features prominently in the memoir. It was part of the Battle of Arras, in Northern France. Mainly between the Canadians and the Germans, over 3 days in April 1917.

The Canadians had to capture the German-held high ground of Vimy Ridge, an escarpment on the northern flank of the Arras front. This would protect other parts of the Canadian military, further south, from German crossfire.

Supported by a creeping barrage, the Canadians captured most of the ridge during the first day of the attack. The final objective was a fortified mound located outside the village of Givenchy-en-Gohelle, and when this fell to the Canadians, the Germans retreated.

This battle was the first occasion when the four divisions of the Canadian Expeditionary Force fought together and it was made a symbol of Canadian national achievement and sacrifice. And we'll find out what contribution our Capt Hovell made to this battle shortly, but of course he wasn't Canadian!

One final comment about the Memoir before we start. There are quite a lot of people and place names which won't mean a lot to most listeners, but I've chosen to leave them in because that's how the Memoir was written. I truly believe that leaving the names in may mean something to you, and you might take enormous satisfaction from that - you might even have your own memoirs that could contribute to the show.

So this is the story of just one Norfolk man’s first world war, Captain H E Hovell.

I’ll leave it there and crack on with it.

Chapter I

The memoirs of Capt H E Hovell – Part One – First World War

It was the spring of 1908. King Edward VII was on the throne and more than a year before Blériot flew the English Channel in his monoplane.

Two boys aged fourteen years sat on a garden wall in Norwich looking at No. 1 of the new boys’ magazine called "The Scout." I think the exact date was April 18th. It was 1908 and [Briton] General Sir R. Baden-Powell [having been a hero in the Boer War in ther defence of Mafeking]had formed the Boy Scout Organisation with the motto "Be Prepared".

How that motto became true six years after. The first page [in the magazine] was by General Baden-Powell, "How I started Scouting". There was also a serial story called "The Phantom Battleship". After much deliberation the boys, Geoffrey Martin Cook and myself, decided to form a patrol of scouts. Cook was the son of Mr. Robert Cook, Reporter of the 'Eastern Daily Press' and local reporter for the 'Daily Mail'.

As Cook and myself were pupils of the Old Higher Grade School, it was only natural we recruited most of the boys, friends of ours, from that school. We got together about six boys, had a meeting and decided to form a patrol and call it "The Cuckoo Patrol".

I wasn’t long returned from Brantford, Ontario, in Canada, the home of the Mohawk Indians, and they had their reservation there, so I was voted Patrol Leader. A boy named Reg Pollard was made Corporal and Cook was Secretary. The great question then was how to obtain the scout uniforms. In those days children were not given very much pocket money - it was thought that it spoilt them.

I myself had two or three coppers on a Saturday. Our parents, like everybody else, knew nothing of Boy Scouts and laughed at the idea. So we had to get things one by one. The main things were a scout hat, scarf, pole, short knickers, scout’s belt and patrol flag. The scarf for the Cuckoo Patrol was grey. It was past Christmas in that year before we were near fully equipped.

A few weeks before Xmas we decided to go carol singing, only to large houses in the country or towards the outskirts of Norwich. Once we ventured up to Crown Point, the home of Mr. Russell, the great mustard man. We were given four shillings by a man in livery, a goodly sum in those days. We of course walked to all these houses covering many miles after school.

It was a Hall just outside Norwich, possibly Dunston - we were invited in to sing to the family and given refreshments after. Wherever it was, it was a Buxton family. We did very well financially - one reason was our uniform, or what we had up to then, which was quite a novelty. Regarding our singing - well, I think it was appreciated!

One of our first expeditions was to locate a suitable spot for our weekend camps and it was agreed by all, that Dunston Common was the ideal spot, this was about four miles from Norwich off the main Norwich to Ipswich Road. We used to leave Norwich for camp every Friday or Saturday night, mostly all weathers with just a waterproof cape which we used as a ground sheet.

We had no such things as blankets or tents, we took food with us but usually found our Sunday dinner by snaring a rabbit, which we cooked in our improvised oven.

During our camping we took long marches passing through many villages. We were laughed at by the locals and very often had to fight our way through. They of course were amused at our short knickers, scout poles etc. which were all new to them. At times we had to run for it. Scouting was unknown to nearly everyone in those days. Little did we know that by 1920 there would be 750,000 scouts [12 years later]

Chapter II

It was winter of 1908 before we met any more scouts or even heard of them. One cold afternoon we were on the road towards Swardeston when we came across some more partly-uniformed scouts and recognised a few of them - they included the Kirby brothers, Tapscott and Bobby Murihead whose father was choir master at Holy Trinity Church, Norwich.

How different things were in those days, the air was pure, not contaminated by petrol fumes and diesel fuels. One could walk on the country roads without fear of being suddenly bumped off. A country of beautiful hedgerows, shady lanes, and tranquillity. One did not have to hop across the road like a [mad] March hare.

There were many footpaths and bridle paths [that] people could use to walk across the fields and enjoy the beautiful countryside. On a Sunday before our dinner on Dunston Common we used to walk round to Stoke Holy Cross and buy stone bottles of ginger beer which cost us a penny each. I think the pub we called at might have been "The Rummer Inn".

Later on we made our own little tents and used to bury them in the ground until the next time we paid a visit there.

A new outdoor swimming bath was opened at Lakenham on the outskirts of Norwich soon after we’d formed the Cuckoo Patrol; many times we left our beds at 6 a.m. and walked nearly two miles to the baths. After swimming we returned home for breakfast before going to school.

We carried on scouting for a long time on our own. Once, we arranged for a week's camp at Somerton, North East Norfolk. This was the first time we hired a bell tent. We sent the tent on by train to Yarmouth and I believe by carrier from there to Somerton. The owner of the Hall where we camped was a Scottish gentleman who kindly gave us permission to camp there. We left Norwich about 10.30 p.m. on a Saturday night arriving at our destination during the next morning. We carried all our food for a week with us. The distance was about 24 miles from Norwich.

[There were nine members of our patrol:]

Apart from Cook, Pollard and myself, the other members of the patrol who were with us for most of the time were, Ossie Ward, Syd Palmer, Harry Loades, Arthur Hubbard, Mace and Alf Stubbs, the latter I am not quite sure about.

Of them, Syd Palmer would be killed in the Somme Battle. Cook, I am told, died in the middle nineteen-fifties. Loades was wounded in France – he returned home and had an operation for his wound, then fell from the operating table and died.

Cook and myself met once in France just after the Battle of Vimy Ridge, he was a Sergeant in the R.A.M.C. I met Hubbard once between the wars, he was on the staff of the Ilford Town Hall, London. The others, if still with us, I should very much like to meet.

We eventually heard during the spring of 1909 that a Mr. Barnes had formed a small troop of scouts. We paid him a visit and soon after joined up with him. He had a shop in Exchange Street Norwich where he sold garden tools, raffia, brass etc. He was a tall solid man, walked with a long stride – wore corduroy breaches, and buskins (leggings).

We held meetings at his shop and carried on scouting under his guidance for some months. Then it became known that a Mr. Claude Stratford had been appointed local organiser and later, I think, district commissioner. We had a large rally when King Edward VII came to Norwich, I believe to lay the foundation stone for a new wing at the Norfolk and Norwich Hospital.

It was a few years before then when I had seen his Majesty and Queen Alexander open the Jenny Lind Infirmary when they were Prince and Princess of Wales. I sat on a large policeman's shoulders and the Princess smiled at me when she passed, that was in 1900. In the same year I saw the first tramcar come up the Newmarket Road, Norwich. I stood in my grandmother's garden at the junction of that road and the Ipswich Road. It was bedecked with flags with the brass hats of the city on board.

During our numerous weekend camps on Dunston Common we learnt many things useful to Scouting to enable us to pass exams. The most important ones, we thought, were called the "Path Finders" and the "Red Cross". In those early days of scouting we had no adults over us and I consider that it was the boys themselves who helped to bring scouting to the level it became. Most of the grown-ups treated scouting as a joke and it was not until the boys themselves brought it to the notice of the people that the grown-ups started to lend a hand.

Anyway, scouting and long marches made us tough and helped most of us to take our part in the activities towards the Kaiser. During my army career I learnt all sorts of ditties (mostly military) some of them unprintable. To mention a few, one of them being the exploits of a German Officer crossing the Rhine; to love the women and drink the wine.

How long I stayed in the scouts then I can’t quite remember, but it was in 1911 that the German gunboat "The Panther" was off the north coast of Africa and everyone thought war was imminent. My father said to me "don’t you think it's time you joined the Territorials?" we shall soon want all able bodied men in the army. Much against my mother's wishes I did join up and of course scouting became a thing of the past as we then knew it.

PART II [The Territorials]

Chapter I

My father had been speaking to a Sergeant instructor of the 1st East Anglian Brigade Royal Field Artillery who had been a member of the famous Chestnut Troop Horse Artillery, before the Boer War. They were stationed in India and went to South Africa from there. In 1911 he was attached to the 1st East Anglians as an instructor. His name was Sergeant Hannent; I was then seventeen years old.

I joined them in July 1911 as a driver, not being quite tall enough for a gunner. As I said before, my mother was greatly annoyed at my joining as such, saying I would learn to swear, drink etc. Anyway I joined in time for that year's annual camp, to be held in Norfolk on "Thetford Warrens", not a good place for the horses, too many rabbit holes.

We moved off from Norwich with [eighteen pounder] guns, limbers and horses, and went by road stopping the first night at Attleborough, where I had nearly a tumbler full of the famous cider made there [Gaymers Olde English cider]. Not being used to it I did not feel a hundred per cent the next morning, when we moved off to Thetford after attending to the horses and having breakfast. The temperature was 91F 33C in the shade during the day, and during the next week it was a record of 2 degrees hotter.

The first full day at camp I was detailed for cook - house fatigue (peeling spuds). During this task I was stung by a wasp; one of the cooks said, "rub this bloody onion on it". I did, the pain seemed to disappear.

When I finished this delightful start to my camp life, in the awful heat I became very thirsty and decided to go to the canteen, which was in a marquee - and have a drink, perhaps a lemonade?

On entering the canteen I saw only one person there, apart from the barman, this was the provost corporal. Knowing that he had his eyes fixed on me, I was afraid to ask for a lemonade. He had a pint pot in front of him so I changed my order to a shandy, thinking it was more like a soldier's drink. When I asked for that he bawled out, "What did you ask for?" I told him, he then said, "No you bloody well don't" and turning to the barman said, "give him a pint of wallop and fill mine up, too. If I hear you ask again for a shandy, I'll knock your bloody block off, or words to that effect. That cost me fourpence the two.

During my week's camp, I'd only a week's holiday then, and that was all one was forced to do if unable to get more holiday. I learnt lots of things unknown to me before; riding, grooming, drill and things connected with the army in general, also the King's English albeit somewhat distorted.

On the whole I found the chaps very nice and always willing to show a recruit the intricate army rules, regulations and not by any means least, the correct way to deal with horses, especially our kind that had never seen a gun carriage or felt a spur before.

After the camp I attended drills each week - and at weekends, tuition in signalling.

During 1911, Ragtime came over here from America; Ethel Levy sang Hitchy Koo, and Everybody's Doing It. In fact came over to this country from America in the 1950's and sang Alexanders Ragtime Band on the T.V. She died soon after.

An American Octette sang Alexanders Ragtime Band. The Two Bobs, also from America, brought ragtime. Then came the Bunny Hug and Turkey Trot. One of my favourites was, "The Mysterious Rag".

We had several church parades to Norwich Cathedral headed by our large brass and reed band. We then wore our full dress uniform with spurs. Our helmets had a miniature round ball on top resembling a cannon ball. Very often the late Earl of Leicester was with us wearing his plumed hat. I think he was Lord Lieutenant of Norfolk then.

Our riding drills were often held at the Cavalry Barracks, using the Cavalry horses.

The 1912 camp was held at Oakhampton in Devon [on the South coast]. We travelled there by train with the horse trucks attached. Arriving at Oakhampton, the first job was to let down the sides of the horse trucks, then push our way in between the horses who were facing away from the open side of the truck, get hold of the heads of two horses and push them backwards down to the platform. One of the two, lifted its foot up and placed it on mine splitting my boot. I had to release my hold of the other horse for a moment and bring my hand over and give it a four penny one to make it lift its foot away from mine.

The camp was a permanent one on the mountain "Yes Tor" used by all Artillery for firing practice and if the clouds were low they used to hit the top of the mountain and rain used to fall in buckets full. There were drying sheds to dry our clothes in.

If the troops went into the town at night and returned in the dark, the only way to find the camp was to follow a line of stones that were painted white.

One night several of us lost our way and had to lie down and sleep until daylight. We were awoken by a peculiar noise. It turned out to be a large number of wild Dartmoor ponies running past and just missing us.

1912 was a year to remember. In April the great liner, "The Titanic" was sunk by an iceberg with great loss of life. The Airman B.C. Hucks made exhibition flights at Norwich. His was the first airplane I saw in flight. If I remember rightly the Australian cricket team played in Norwich, and in the September of that year the late Lord Roberts came to Norwich as President of the "National Service League". He was Field Marshal and Commander-in-chief of the British Army. I was one of a guard of honour at St. Andrews Hall supplied by the 1st East Anglian Brigade H.F.A.

The hall was crowded and he told the audience "That a great Nation with a vast army was waiting to pounce on us" or words very much to that effect. There was a cry of "Bloody old scaremonger". How true his words were in two years after.

He stayed with the late Earl of Leicester at Holkham Hall. I possess a letter written by Lord Roberts from Holkham Hall soon after the meeting. During 1912 there was coal strike lasting about five weeks, and I think Mrs Pankhurst tried to address a meeting in Norwich towards the end of the year, about votes for women.

The following year 1913 we held our camp at Lydd for firing practice. During the first and second weeks we went [just along the South-east coast] to Shorncliffe near Folkestone. We went by road from Lydd and had some difficulty in getting our horses to pull the guns up the hill.

While in camp there was a competition for the best kept pair of horses. One of the sweats (soldiers) told me to go over to a pub called The Royal Oak and buy some stout. "That will bring their bloody coats up" he said. This I did and won a prize. I won a pair of military hair brushes in a real leather case. This was presented to me at a smoking concert later that year by the Earl of Stradbrook. It was very heavy work driving, especially as the horses had never been in a gun team before. I started as centre driver, then wheel, after that lead.

Chapter II

At one of our afternoon riding drills about twenty of us were waiting for men of the Lancers to bring out the horses from the stables. When they appeared, one of the horses, a beautiful looking creature, an Arab horse, was playing up rough and I saw the troopers were laughing, knowing the horse would be too much for me.

It turned out that when the line of horses stopped, the man who stood opposite each horse had to ride it. Well it turned out that the horse mentioned stopped opposite me.

Everything was alright until we got on to a large heath, and the officer in charge shouted out "trot, canter then gallop".

The horse and myself left the others a long way behind and only with great difficulty did I manage to pull it up before we came to a large hedge or number of high bushes, and lucky I did not rupture myself.

The officer carried on and said they should not have brought that horse out. He told me to take it back to the Barracks. It took me, and did not stop until he was in the stable. I heard that someone had to go up before the C.O. for that little bit of fun.

We did a weekend camp at Colchester with a regular Battery on the Abbey fields. Then it came to November 1913. I had to leave Norwich for further experience in my profession.

I went to a lovely little town on the borders of Suffolk and Essex on the river Stour mentioned by Charles Dickens in "Pickwick Papers" as Eatenswill also the home town of the famous painter, Gainsborough". I spent about ten months there and about the happiest months of my life. Very friendly people and a lovely river where I spent a lot of my spare time during the summer of 1914.

As there was not an Artillery unit anywhere near that town, I left the Terriers [the army reserves]. When I arrived in the town on a wet November evening I thought that my stay would be short. Everything looked so gloomy, no cab at the station, only one person outside, a woman who later I was told, was the town prostitute. She said good evening and I answered back that I did not agree with her.

After a meal at my lodging, which had already been booked for me, the rain was now only a drizzle, so I ventured forth to find a decent place for refreshment. Having got into one of the main streets leading out of the town to the Essex side, I saw a very large policeman with a lantern in his belt. I stopped and asked him if he could direct me to a nice hostelry where I could obtain a drink?

He said "Well I be going down this way. If you come along with me I can put you right". After walking about a quarter of a mile he stopped and pointed to a very old looking building, saying "This is an old Dickens Pub where you can get a nice drink of beer. If you go through this door and turn left. It occurred to me that perhaps I ought to ask him if he would care to imbibe, not thinking for one minute he would be allowed to accept. But to my surprise he said, "That's what I be a going to 'ave."

Well I went inside and ordered my drink, asking the man who served me to give the Bobby a drink, and I would pay for it. Later he came back and said the constable had been served and it would be five pence for his. It turned out that he had a pint of beer and a drop of rum in it. This was quite a lot for a youngster to pay in those days. The name of the hostelry was "The Bull Inn" now I am sorry to say, pulled down.

The Manager then, was one of the sons of the owner of the local brewery who owned the Inn and I became quite friendly with him during my stay.

The Xmas Eve of 1913, the local blacksmith, a man by name Turk, made some egg flip, something of nearly everything in the house was put in it. I was told this occurred every Xmas Eve and all customers were given about half a tumbler full.

Some of the local tradesmen used to play crib in the little room I used for whiskeys. It cost 3d a shot and was twenty under proof, not thirty as today. I called there in later years, about 1960, and things appeared much about the same then as they were in 1913-14, apart from the price of drinks and cigs'. The town was Sudbury. I understand that Inn was demolished later, too.

Names of people I got to know very well during my stay in the town were Kilby, Halestrop, Openshaw, Wing, Grimwood, Jones, Skitmore and Parsons - also the reporter of the local press whose name I cannot recollect.

August the 4th 1914 came the Great War, and the curtain came down on those pleasant days, and I don’t think it has ever properly risen again.

Chapter III

I left the Suffolk Town not long after the outbreak of war and seriously thought of joining up, but my parents advised me to carry on with my work as I had my future to look after, and if the war lasted many months then it would be right for me to join. I don’t think my mother wanted me to become involved in the conflict. So I went to a south coast town for a few months and met an old friend of mine who was living there, and a friend of his.

We decided to join a crack London horse regiment. They would not accept my friends but would me, so I would not join. After getting fed up with civilian life I decided to go back to Norwich and join my County regiment and enlisted in the 6th Norfolks.

Not long after enlisting , the O.C. at the depot called for me and said I ought not to bloody well be in that regiment. The R.A.M.C. was the place for me, owing to my vocation. I might mention here my father lost a good sum of money owing to the war, and really could not afford to send me up to London for the studies necessary for me.

When the O.C. told me to join the R.A.M.C. I said "Very well, transfer me" and this he did, and by June 1915 I was in camp at Windsor Great Park.

We had several long route marches and after one I developed a large blister on one of my heels. Being told there would be another march in two days, I wondered if I could make it, my foot hurt so much. Then I decided to speak to the R.S.M. who was old Ex Norfolk Regt' man and a stickler for discipline. He said, "What a blister boy! Well report to my tent at 5.30 in the morning, we will soon get rid of that".

Promptly at 5.30 a.m. in the morning I made as much noise as I could on his tent flap and after a time he stuck his head out, his eyes half closed and a flushed face, after a thick evening I thought, and demanded to know what I bloody well wanted? I told him and he then told me to take my bloody boots and socks off and walk round the park for half an hour, and keep on the move. "That will cure your bloody blister".

I went on the next route march, about twenty miles, and returned very tired, but no trouble from blisters.

The camp was called "Bears Rail Camp", there were a lot of deer about. Soon after this last march I was told to report to the orderly room, as the Captain wanted to speak to me. I wondered what the hell was the matter. The Captain said, "You are in the dental line are you not?" I replied that only the mechanical side of it at present. "Well, he said, you are going to be on the operating side in the near future".

There were several thousand troops at camp in the park, and a large number had toothache. No doubt leaving feather beds and having a different diet, played on the weakest part of the anatomy - that being the mouth and teeth.

He told me that himself and officers attached to our R.A.M.C. were nearly all doctors and did not have much luck in extracting molars, so they decided that I should have a go. As I was in the army and had been given an order, it was up to me to obey, otherwise I was for it.

The next day I was taken to a bell tent where inside was a table, one chair, an enamel jug, also a basin (for spitting into), an enamel cup and a leather case containing three pairs of forceps - no syringe or local anaesthetic.

The troops had been told, and it was not long before I had many patients. Apparently all could not be catered for by local dentists. They - in their innocence - came to me like lambs to be slaughtered. I certainly did my best, sometimes my worst.

Those teeth I couldn’t extract, I just left. Very often if successful the soldier would say "Well now you are about it you might as well take this bugger out as well", and very often I was offered money, a shilling or two by those who were pleased to be relieved.

This went on until we had to leave the park owing to deer at that time of the year. We moved to a camp that had only been formed about a year. It was a sea of mud after the rains came, and it was called by us "Halton in the mud". Now I believe it is an R.A.F. training centre. Before we left Windsor we were warned for active service and dished out with drill uniforms etc. [Warned means put on notice]

We had a farewell concert, but at the last few hours the trip was cancelled much to our disgust. We little knew then how lucky we were as the boat we had to travel on went to Alexandria and transferred all the details to the Royal Edward, which was torpedoed and sunk before it reached Suvla Bay [at Gallipoli]. [Listener you don’t want to know what happened at Suvla Bay. You really don’t. But if you do - then listen to the excellent memoirs of Fred Reynard in Episode 16 on the battle of Gallipoli].

Before the concert we had been told Royalty would be present, but we failed to recognise anyone different to those who helped in the Y.M.C.A. But rumour was that the Lady who gave us tickets for our money to buy tea and buns etc. was Princess Alice, Countess of Athens. She was very pleasant and good looking and it was that Lady who was present at a plaque unveiling ceremony at a hospital, at which I was an Honorary some eleven years later.

Lord Kitchener

Lord Kitchener a Boer War General under Lord Roberts was made Secretary of State for War in 1914 and raised a body of men, before conscription was introduced, called, "Kitchener's Army". Owing to a shortage of khaki they wore blue uniforms for a time. Lord Kitchener left for Russia in a bad storm in June 1916 on a cruiser called Hampshire which struck a mine laid by a U-boat. Only twelve survived and Kitchener was among those drowned and his body was never recovered.

At Halton Camp I carried on with the tooth business, and also helped with vaccinations for venereal cases. At times I joined the rest in long route marches about 20 to 24 miles in full marching order. I had a few weekend passes to London - once when a zeppelin dropped bombs, one landing in front of the Lyceum Theatre. I saw a photo some years later of the crater with several soldiers looking at it, including myself.

At last a dental surgeon was posted to our field ambulance. I asked for more pay just before he arrived, for doing dental work, but was unlucky.

My friend Allan Miles and myself were getting very fed up waiting to be sent overseas, and when a notice was posted up asking for men with a knowledge of chemistry to volunteer for the Special Brigade, we volunteered. It was a chemical warfare outfit and the dental surgeon hoped we would be accepted if we really wished to go. But he added "woe betide you if you are sent back".

It turned out we were the only two sent. We travelled by the Cornish Express to Plymouth and were told to get the chain ferry over to "Tor Point" on the Cornish side of Plymouth Sound. This we did, but not that night as ordered.

It was next morning we went over and stopped at Tregantle fort for a drink, then went on to Whithnoe (that was the headquarters of the Special Brigade in England) a camp where the men were equipped and sent out to France within about three or four weeks.

I had a few days leave before leaving Southampton for Le Havre on a very rough night. Most of the troops were sick and we decided to sleep on deck and get wet which was better than the stench below.

We spent that day and the next night at the rest camp at Le Havre. On the way in we met a battery of Australian Field Artillery coming out. It was raining and they were covered in mud, and the language was just terrible. The horses were playing up and I could quite imagine the drivers’ feelings from past experience. The next morning we moved off to Rouen. Here we took a train to our depot in France at Halfaut. There was a chateau here that Earl Haig had used as his headquarters.

I will now endeavour to give you a brief history of the "Special Brigade" and its object.

PART III

Chapter I

THE SPECIAL BRIGADE

The special brigade was formed in the spring of 1915 in answer to the German poison gas attacks during the second battle of Ypres.

An urgent appeal was made for men with a knowledge of chemistry for special duty. All sorts of men of science came forward, plus men for training the latter. Great secrecy was maintained about the whole matter. In the first place three companies were formed and called Royal Engineers; it would not have done to have called them "Poison Gas Companies" as they would have been shot on the spot if captured.

As time went on, more companies were formed, some using cylinders for gas clouds and were named A.B.C. and so on.

Then another four companies were set up using the heavy Stokes trench mortar for gas shells, thermite and smoke shells or bombs for daylight raids by the infantry. These companies were numbered one to four. No. 4 happened to be that company I was posted to.

[The Stokes mortar was a British 3-inch trench mortar designed by Sir Wilfred Stokes and was issued to the British and U.S. armies amongst others. It was a smooth-bore, muzzle-loading weapon for high angles of fire. The British Army was at the time trying to develop a weapon that would be a match for the German Army's Minenwerfer mortar, which was already in use on the Western Front.]

The cylinder companies had revolvers and the mortar companies had rifles and bayonets. The whole brigade was placed under command of Major C.H. Foulkes a regular officer of the Royal Engineers who rose to rank of Major General, a splendid man and leader.

I attended the first and only reunion of the Brigade at The Cavendish Hotel at Eastbourne on September 5th 1965, the anniversary fifty years to the day when at the age of ninety – There were also 134 old comrades including one who flew over from Canada, one from South Africa and one from Australia. Of the 134 who attended few indeed were under seventy years of age.

[The Battle of Loos took place from 25 September – 8 October 1915 in France on the Western Front, during the First World War. It was the biggest British attack of 1915, the first time that the British used poison gas and the first mass engagement of New Army units. Despite improved methods, more ammunition and better equipment, French and British attacks were contained by the German armies, except for local losses of ground. British casualties at Loos were about twice as high as German losses.]

At Loos the discharge of gas into the enemy's trenches caused great havoc and many casualties. Chlorine gas was used. Later phosgene and other gases were introduced. The Special Companies also suffered many casualties in the Loos Battle.

A new weapon was introduced a little later invented by a Captain in the brigade and named after him. It was called "The Livens Projector". These projectors could be used in batteries and caused a great number of casualties. The batteries sometimes had several hundred projectors and could fire gas, thermite, burning oil and smoke.

The trench mortar companies were used to cover the infantry with a smoke barrage. Very often during daylight raids twenty five pound gas shells were fired from mortars before the smoke to demoralise the enemy. During the raid, ten rounds rapid were fired by each mortar followed by one each minute up to an hour.

Frequently the infantry had to be followed up. This meant moving the hundred pound guns and sixty pound base plates etc. also shells. Directly the mortars opened up, the Germans let go all they had in that sector at them. Very unpleasant, and often caused a lot of casualties.

Very often the mortars had to be sited in saps forward to the front line and emplacements prepared with sandbags. Sometimes these were very close indeed to the enemy and they could be heard talking. The forward gun team were given mills bombs in case they were attacked. The infantry also had stokes mortars but these were smaller and fired small shrapnel shells rapidly for a few minutes then stopped.

By the end of the war we had the Germans well beaten in chemical warfare. I was confident that when the second world war started the Germans would not use gas.

Chapter II

After the Somme Battle and towards the end of November 1916 we were billeted in a farm house barn at Halfaut and slept in the loft with cows and horses below us and a large midden [refuse heap] not far away. The family used to use this as their lavatory.

On the Xmas Eve 1916 two of us walked down to a small town between Helfaut and St Omer and bought two bottles of Dewars whiskey at 3/6d a bottle [say less than 20p, 25c?] twenty under proof not thirty as it is today. We carried both back to our billet for a little Xmas party arranged for next day. One bright fellow made out a little souvenir programme for each of us which we all signed, including the French family and their friends who’d joined us. Of course the whole thing was exaggerated. We simply drank whisky, liqueurs and sang songs, and also had cigars. The next morning came the reckoning and we all felt very sorry for ourselves for having to be on parade so early on a bitterly cold morning.

The Xmas menu is printed on page…..from the original still in my possession.

Most of the fellows were chemists or budding scientists. One was a Professor in physics who lectured us after the war when I was a dental student.

It was plain to us later, when in the trenches, that at times we would have got on better if we had been 'all in wrestlers'.

One day we were informed that Earl Haig was to pay us a visit for a display by us of a new shell container called thermite - aluminium powder mixed with a metal oxide - which when ignited emits a great heat. This was then to be used in twenty five pound mortar shells with a time fuse to burst over machine gun nests etc. This was used later for other purposes in the Second World War.

During this exhibition one of our men was badly injured. We used these shells at later dates. One day we were warned that we would be wanted in the line for a daylight raid by an infantry regiment. The next day we boarded some of the Old Bill London buses and made our way to a crossroads near Vermelles where we made our billet in a ruined church.

Not far away, a battery of field guns was in front of us. Our shells were brought up later to the communication trench called "The Fosse Way" apparently the Leicesters had named it that. [The Fosse Way was a Roman road in England that linked Exeter in South West England to Lincoln in the East]

After going down a trench a good way, we came to an opening to a very long underground passage some sixty feet below ground built, I think, by the Germans when they held that part of the line.

After a good walk we came to some steps leading to the front trench. At that time the trenches were in quite good condition, with not many strafes, and known then as a quiet part of the line. The Saxons [a German corps] I believe held the trenches opposite. We built our emplacements and prepared for action at zero hour. At a given time we opened up by firing ten round rapid from each gun, followed by one a minute for about an hour.

[Listener just in case you get confused by this strafe term, obviously in WW2 it was usually referred to in connection with aircraft, strafing the ground troops with rapid fire. But in WW1 it could also involve runs by land or naval craft to similar effect.]

We had quite a lot of dirt fired at us as soon as we opened up and things began to hum. The idea of the raid was to capture prisoners. Some of those of the raiding party who returned were wounded.

One poor little fellow had part of his foot hanging off in his boot. He was helped to the first aid post as soon as he got back in the trenches. The raid was at Halluch. The Hohen Zollern, Redoubt and Brick Fields; the guards were in action there in 1915 and lost heavily. After the raid how those trenches had altered.

I always had a great sympathy for the infantry, half their time up to their knees in mud, nearly always being shelled, covered with lice and very often "over the top". When not in trenches they were in dugouts, sometimes a few wire beds to lie on and infested with large rats. The old song went :-

rats, rats, big as bloody cats;

[There were] rats, rats, big as bloody cats; in the quartermaster’s stores – Google it]

and so on.

We sometimes spent a week in the line, but were frequently moved about to different sectors and fronts. I noticed that some of the smaller men were in the infantry and one found a lot of the bigger ones as drivers of transport and never went nearer the front line than the beginning of a communication trench.

They were paid six shillings a day, the infantry a shilling a day for fighting. But although on the small side, the infantry were tough and trained up to the hilt. There is nothing worse in warfare than cold steel and hand to hand fighting. Here I will mention the supporting troops such as the Royal Engineers field units, Signals, R.A.M.C. who all had heavy casualties.

The Artillery were targets for the enemy and suffered heavy loss, especially the Field Artillery. It is said that the average life of a Subaltern in the infantry was three weeks.

After our strafe we returned for a short time to Pihem and Hallines, two villages near Helfaut. The weather was still bitterly cold and snowing. Again we were billeted in barns and outhouses. We had one fellow who would not wash and he was finally washed by force. There was thick ice on the pond but with a hole large enough to duck him in.

In about two weeks we again went up the line to Billers au Bois, and went in the trenches again at Vimy Ridge. We prepared our emplacement for a raid by the Canadians to capture prisoners to gain information for the big attack that was to come. Of course we did not know about this then. It was intended that we’d fire gas shells during the early hours of the morning and follow with smoke for a raid by the Canadian infantry. This was on Monday, but the wind was wrong for the gas so the raid was postponed from night to night, and I think it was the Thursday before the wind turned.

In the meantime, the Germans had got to hear of this and were all ready for the attack. The Canadians went over the top behind our smoke barrage, but were mowed down with very heavy losses. We heard that they lost just seven short of a thousand men in about ten minutes, including two colonels.

They were all buried in the cemetery at Villers au Bois. It was a terrible half hour. The Ridge shook like a jelly and in spite of heavy loss, the infantry captured their prisoners. Every gun the Germans had in that part of the line fired at us. It was a machine gun fire that the infantry had to face, and it was very heavy.

About four days later we read in a copy of "The Daily Mail" the following: "We carried out a successful raid South East of Souchez in which we captured forty prisoners". That's all the people at home knew about it. After that show my friend Miles and I were sent down the line to a place called Chequers for a course on the latest methods of first aid for modern warfare.

During a few days there I had violent toothache and went to a dentist there in the forces who failed to get it all out. I admit it was a shocking, broken down, lower molar. I suffered agony for a few hours and tried to drown it with a number of glasses of port wine. We went back to our unit then at Le Breby for a week, then back to Vimy Ridge billeted in a cemetery at Carency not far behind Vimy.

Before writing about future events, I’ll mention the night before the last strafe. I was detailed with another man to go to the light railway that ran from behind the lines to the foot of Vimy Ridge.

The trucks containing rations for that sector or corps of the Canadian army were drawn by either six or eight black mules, and usually arrived about the same time early in the evening. I was told before it arrived that fritz usually fired a salvo or two of whizz bangs (quick firing light shells) which the troops used to call by that name owing to the noise they made.

This particular evening was no exception. With some of the Canadian we formed a line from the trucks to the dump where the rations were dished out in sacks already marked for various regiments etc. when suddenly 'bang' it started. We ran a short distance for cover in a shallow trench. Some were hit and a man next to me in the trench was badly hit in the head with shrapnel and I don't think he survived it. After a few minutes it was over and when we started unloading again, the mules were still standing there and not one was scratched or the men in charge of them.

In the daytime a light engine used to pull the trucks. The trucks were also used to take the dead down the line after they had been sewn up in blankets. Our section travelled down from the ridge several times sitting on the dead.

Chapter III

The Battle of Vimy Ridge, Easter Monday, April 9th, 1917

From our billets at Carency we went into the line each day to carry shells etc. and prepare for our part in the coming battle. Our way led us through trenches, on duck boards, called the Arras Lines until we came to an open part at the foot of the ridge called "Death Valley".

The first objective was a tunnel burrowed under the Ridge called "The Ding wall Tunnel". This was situated, at the foot of the highest part of the ridge called "The Pimple". The Pimple was held by the Germans at the time - once it was captured, but lost again later.

Our guns were placed in different positions on the ridge, in emplacements. Large holes dug and filled with sand bags. Most of the Sunday the day before the battle started, we carried boxes containing our shells, two in each box, slung over our hich we had on our shoulders. The boxes had rope handles on each end. We carried them from the tunnel along a trench called Wilbour Walk to a part of the ridge called Charing Cross. Wilbour Walk was mud nearly half way up our knees. I was third in the file at one time when my right boot came off. I had to stop for a few moments and feel for it in the mud, empty the mud out of it and put it on again for the time being. By doing this I lost my place and then was about ninth in line.

Before the first man reached Charing Cross a Jerry dropped a five nine shell in front of the line. The first man had part of his right arm blown off as he held the box of shells on his rifle. The second man escaped, but the third lost the top of his head, napoo [finished].

He was a little fellow, his first real touch of the line, and he came from the North-East of England. It was very sad later when, what was left of us, got back to Carency a parcel was waiting for him containing, among a lot of things, some coloured hard boiled eggs for Easter sent by his Auntie with love.

It’s been raining all day before Easter Monday. We were soaked, cold and tired. A man was sent back to Carency for a rum jar. Luckily he was not killed going so we had a small drop of rum to try and warm us up.

During the Sunday before the attack my friend's legs gave way and the O.C. told him to go back to Carency as he would be no good to us with a bad leg and unable to walk properly. He had a malformed hip. He saw the fireworks from our billet and told me afterwards "he never thought anyone could come out of it alive". All through the night our guns were blasting the enemy's trenches and supports, we could feel the draught of the field guns and howitzers that were wheel to wheel behind us.

Zero hour came at 5.30 a.m. on the Easter Monday morning. An order was given out that no one should stop to attend to any wounded, but to keep on with the attack. I cannot remember how long we had been sending out smoke shells from our mortar, but suddenly a 5.9 inch shell must have dropped a little above us, and we were put out for a time. When I came round I saw our mortar was nearly covered with earth and the Corporal was just coming to. Another of the crew, had heard just before we came in the line, that his wife had been playing up at home which upset him very much. Apparently the noise had turned his head altogether as I saw him running away screaming with his arms waving above his head, covered with mud.

That only left two of us to carry on.

We had to clear the space and put some more sandbags under the baseplate which had, with the guns, sunk deep into the mud. We carried on the good work until we had fired eighty rounds. In the meantime the Canadians had advanced a good way and the German fire had decreased quite a lot. We never heard what became of the fellow who ran away; he was possibly blown to blazes.

At that time we were attached to the Canadian Fourth Corps - also there were some Middlesex machine gunners near the pimple, the highest part of the ridge just above us to our left. Scottish regiments were fighting on the right of the ridge near Mont-Saint-Éloi.

When we came out of the line about two hours later, we passed through what was left of the place called Souches, the river by that name was full of skeletons. Some of them appeared, from the remnants of uniform left, to be Ulans, German Cavalry. They’d been used earlier for scouting and carried lances. Also, there were many civilians killed there.

Before the advance it was unwise to go that way as it was under observation by the Germans. During the time on the ridge I was very lucky not to get a blighty - or worse. As it was, I got only a small injury and did not report same, but have very often felt it since…

We went to our billet at Carency not far away from the ridge and I found several weeks mail waiting for us. My father always sent me a twenty packet of Players with a 2/- piece placed in between the two rows of cigs twice every week so I had plenty to smoke. Before then I had only the army ration of cigs - two packets of Robin every Friday.

We met a battalion of Norfolk going forward as we came out down the garrison road leading to the ridge. The Fourth Canadian Division had had a hard task when advancing - they had to contend with some very deep underground tunnels occupied by the enemy. Phosgene gas shells were fired by the Special Brigade prior to the advance causing many German casualties.

During the Vimy battle our O.C. who stood a few feet from our gun, in a part of the trench, was afterwards given the M.C.

I am sure this battle was the turning point of the war, the largest concentration of artillery and trench mortars ever. The advance in an hour or two was very much greater than during the months the Somme battle lasted. The Easter eggs we got were very different to those we had during the past years, and no silver paper round them.

After that last affair we spent a few days at Villers au Bois. A Canadian band played sometimes and during those few days I saw a Canadian Private eating tinned lobster with a madeira cake he bought at their canteen, a queer mixture.

Our next move was to Givenchy-lès-la-Bassée for more smoke work and daylight raids. It was somewhere here we entered the trenches under a ruined house that was called the "Maison Rouge", all that was left of it were red bricks.

Later we went for a week's rest to a mining town called, Les Brebis, but we were recalled to the line in four days. There we had the use of miners’ baths and got rid of "some of our visitors". Marching from there back to a big gas strafe at Bulluch we passed an estaminet or café, similar to an English pub. A soldier was strumming on a piano well out of tune a new song to me called "If you wore a tulip, and I wore a big red rose". I’ve always remembered that song.

In this raid we fired hundreds of twenty-five pound gas shells in a few minutes, we heard the Germans had many casualties. During the next two months we carried out a number of strafes in several parts of the line including two at Festubert, one at Bulluch and one at Loos.

The weather became very hot and I remember one night, in our billet at Beuvry, we all decided to take our shirts off (this we usually did only to change them which was rare) as between the heat and the lice it became nearly unbearable. There was only one man in our billet who would not, he said "I have been out here now eighteen months and the buggers have never beaten me yet".

We slept that night round the billet, our heads resting on our packs and at our feet our shirts. The next morning I woke up and thought my pack was extra soft. When I looked, it was a shirt that my head was partly on. It appeared that during the night he could not stand the itching any longer so he took his shirt off and threw it, and it landed on my pack.

Passing through fairly large towns well behind the line, one saw at times queues of men waiting to be admitted to various establishments names such as No. 4 The Black Rabbit etc., etc. These did not interest me, too many eating off too few plates.

Very often those in command did silly things, or perhaps did not take wise precaution. I remember when we were at Beuvry one fine sunny morning, we had all our guns out cleaning and polishing them during a day’s "rest" from fighting. During this operation a German plane flew over us. Instead of [command] moving us, we were kept in the same spot in the school playground (no school there then of course) and later in the day the German guns blasted us with a number of rounds of shells, killing two of our number. One I remember was a nice fellow they called "Gussy".

In this town a few civilians were still living mostly to make money from any troops staying there - but not all of them did that as they were within range of the German guns. However, they were not fired at very much - only when the Germans knew troops were there.

During my stay with the company we took part in many strafes including the last one at Festubert. Here there were few trenches, mostly only a few shelters of corrugated iron to protect as much as possible from shrapnel. The ground was boggy.

After coming back from this raid at Festubert and having a meal, I suddenly felt very queer and fell over, with severe pains, and in a state of collapse. A medical officer was called and he thought perhaps the water we drank was the cause. He ordered me to the 18th casualty clearing station a few miles away and I was put to bed with a very high temperature. My shirt was changed, thank goodness, and I was given tablets etc.

But I became worse, so they decided to send me down to a base hospital. I was taken with others, in a field ambulance to Bethune in the morning. When I was arriving there, the Germans were shelling the station. I was put in bed in a hospital barge on the La Bassée canal. The bottom of the barge was converted into a hospital ward; what terrible cases there were there.

I recall feeling very bad then with a high temperature. I still have the chart on a card used by one of the R.A.M.C. orderlies. We were taken down the canal to the Casino at Calais which was turned into a hospital. The medical officer who examined me asked me what unit I came from. When I told him he said "It will be some time before you are able to hump trench mortars that size about" and marked me for Blighty.

The next day I was put on a stretcher with a label tied on me (this I still have) and put on a hospital ship called "The S.S. Newhaven" and landed at Dover. My head then felt terrible. The medical officer had said "No doubt the gun fire gave you shell shock as well". My label or tab was marked P.U.O. which meant, Pyemia of Unknown Origin [blood poisoning].

I later found out this was caused by lice and called, trench fever. Laying on the stretcher on the landing stage at Dover I was asked which town out of three I would like to be sent, as three hospital trains were waiting. Their destinations were Norwich, Brighton and Nottingham. I said Norwich or Brighton. Soon after the train I was in started, the medical officer came round and I asked him if it were Norwich or Brighton they were sending me. He said neither as I was bound for Nottingham.

I never regret being sent there. Carrington Hospital was a school before the war. When I arrived there it was nearing the end of June 1917.

During my stay at the hospital we were taken to a Garden Party; tea and entertainment at the "Plaisance" Wilford Lane by kind permission of Sir Jesse and Lady Boot of the well-known firm "Boots Chemists".

From 3 p.m. to 8.30 p.m. we were amused by the N.P.F. Concert Party and the Plaisance Band for those who could dance. The accompanists were Nurse Cotterill and Mr. W. Titterington. I still have the programme.

From Nottingham I was sent to a nearby town of Southwell for convalescence in a house near the Cathedral called Burgage Manor - excellent people the matron and staff. After about a month there I had leave and was sent to the Command Depot at Thetford in Norfolk to prepare us for another continental holiday. But no fifty pound spending money!

Chapter IV

At the command depot we were arranged in groups from 6A down to 1. If you’d not recovered very well you started in 6A and gradually got down to 1 when you were soon sent back to your depot and over the channel again. It was during my stay here I met a soldier who had some verses typed on a piece of paper (No, not the sort of paper you think!)

I had heard them quoted before. I did copy them down but lost the paper. I have been trying to remember them during my period writing this and will try to remember them. I do not agree with them altogether but there is some truth to be said regarding them.

[The term OBE is the Order of the British Empire – awarded to British people for distinguished service to their country:

RFC – Royal Flying Corps

LSD – Money!]

I knew a man of industree

Who made large bombs for the R.F.C.

He pocketed lots of L.S.D.

And then they made him an O.B.E.

I knew a woman of pedigree

Who asked some soldiers out to tea

She said "Dear me" and "Yes I see"

And she they made an O.B.E.

I knew a man of twenty-three

Who got a job as a fat M.P.

Not caring much for the Infantree

And he also was made an O.B.E.

I knew a lady fair to see

Who put rolls of paper in the W.C.

And soap and towels in the lavatree

And she too they made an O.B.E.

I had a friend - a friend, and he

Just held the line for you and me

And kept the Germans from the sea

And died without the O.B.E.

Yes he died "without" the O.B.E.

I made my way from 6A down to No. 1 and went back to the Special Brigade Depot in Cornwall. After staying there for a short while, instead of sending me overseas I had orders to go to the Experimental Station at Porton, Wilts! Here we were to be used to a certain degree as guinea pigs. It was at Porton that chemists and scientists helped to find antidotes to all that the Kaiser threw at us in chemical warfare. We also developed new gases etc.

When I first arrived there they were experimenting with smoke through ships’ ventilators; Commander Brook was there (from Brooks fireworks). We knew soon that they were experimenting with smoke barrages from fast naval motor vessels, as we did on land sometime before. It was for the St Georges Day attack on Zeebrugge, April 22nd 1918 to try and block the Harbour that Germans used for their U boats.

We also had many animals at Porton used for experiments. Various people gave dogs and cats; also we had monkeys, goats etc., etc. These were put in gas chambers to ascertain various concentrations of gas to be used. We also had to go in these large glass chambers with either German or our own respirators on, until we found the gas coming through. When we came out we were given ampules of chloroform to inhale which more or less localised the gas. Our chests felt as if we had been wearing Victorian stays. Many times I and friends went into these chambers.

Once King George V and staff came down to look at us. At times various well known men in the Government of the day came down.

After some experiments we got six days leave to pull ourselves together. When the Germans used mustard gas this was also part of the work done at Porton to overcome the effects of same.

In November 1918 some of us were sent down to the French Experimental Station at Entressen near Arles in the South of France. Here we found the weather to our liking and we lived in tents alongside the French Experimental troops.

The French released the gas and we were placed at various distances wearing either the latest German or British respirators. We also had dogs with us. The British respirators proved to be able to last longer in concentrations of gas than the latest German respirators.

We had a number of these experiments. Once an officer asked me to put my respirator on and bend down over a gas cylinder which he turned full on.

At the time we stayed at Entressen we had been told that half a million yanks were there, ready, if the Germans did not agree to an Armistice. Also our gas was ready. The place was full of Americans and they did not get on very well with the French colonial troops stationed at the Barracks at Arles.

We got taken once to a little fishing village on the Mediterranean called Martigues, for a change from gas.

The best job I saw during the war was at Arles Station. A small body of men had been stationed there since the start of the war, and their job was to prepare food parcels for troop trains going through to Italy. They all looked fit, well fed, and comfortable.

I often wondered if they ever went home again. Possibly if I had been one of them I would not have done. On our journey down to the South we stopped in Paris for a day or so

It was on the Gar de Lyons station in Paris that our lads sang a new song, out about that time, called The Parson's Waiting for Me and my Girl. A huge crowd gathered round - most of them on their way to work. It was about 8 a.m. and they thoroughly enjoyed it.

Returning to England and Porton Camp we did not do much as an Armistice had been declared. Some of the men began to get their discharge, commonly called their 'tickets'. I managed to get mine in the January of 1919 and returned to "A land fit for heroes to live in", so we were told. Soon after being demobilised I joined the Comrades of The Great War in St. Faith's Lane, Norwich.

For a long while before that I had not been at all well; nerves, headaches, a feeling of distress. My weight gradually went down to a very low level, later to six stone nine pounds and I had begun to feel that I should be blown away.

It took me a year to pull round and then I went off to London to study for my Royal College of Surgeons diploma in dental surgery. During the four years or just over, I was doing this. I had one breakdown with my nerves which delayed me for a few months. All this trouble had been caused by "blast".[PTSD]

Before I finish these memoirs of part of my life from 1908 to 1918 I should mention that my younger brother joined the scouts after I left and attended the review by King George V at Windsor in 1911. Also, both served in the army; one in Salonica, the other younger one in France (aged 19 years and was killed three weeks before the Armistice in 1918)

Prior to returning from war to a troubled peace I feel that it would not be out of place if I resurrected a few of the soldiers songs and ditties sung going up to the trenches and on the march during the war. For instance:-

He's a ragtime soldier

Happy as the flowers in May

Fighting for his King and Country

For a lousy tanner a day

---

Après la guerre fini

English soldat parti