9 Dunkirk Diaries of Major Leslie Petch OBE WWII V.2022

Original war diary discovered by family, WWII

"Champagne and scrambled eggs for supper!"

A dramatic blow by blow account of the Major's writings.

The personal war diary and letters home from Major Petch offer a unique glimpse into the lives of the British soldiers during Dunkirk in 1940 WW2.

"It'll all be over when it gets hotter" was the prevailing opinion.

This changed in a matter of days as the weather did get hotter but the soldiers began a desperate fight for their lives in the face of Hitler's blitzkreig.

Would they get off the beaches at Dunkirk?

More great unpublished history - of the Second World War.

Show notes at www.FightingThroughPodcast.co.uk

Please rate and review - Thanks!

Please note that photos below may or may not display depending on which listening platform you’re using

Best podcast for World War 2 history and the second world war

Interested in Bill Cheall's book? Link here for more information.

Fighting Through from Dunkirk to Hamburg, hardback, paperback and Kindle etc.

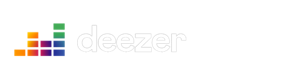

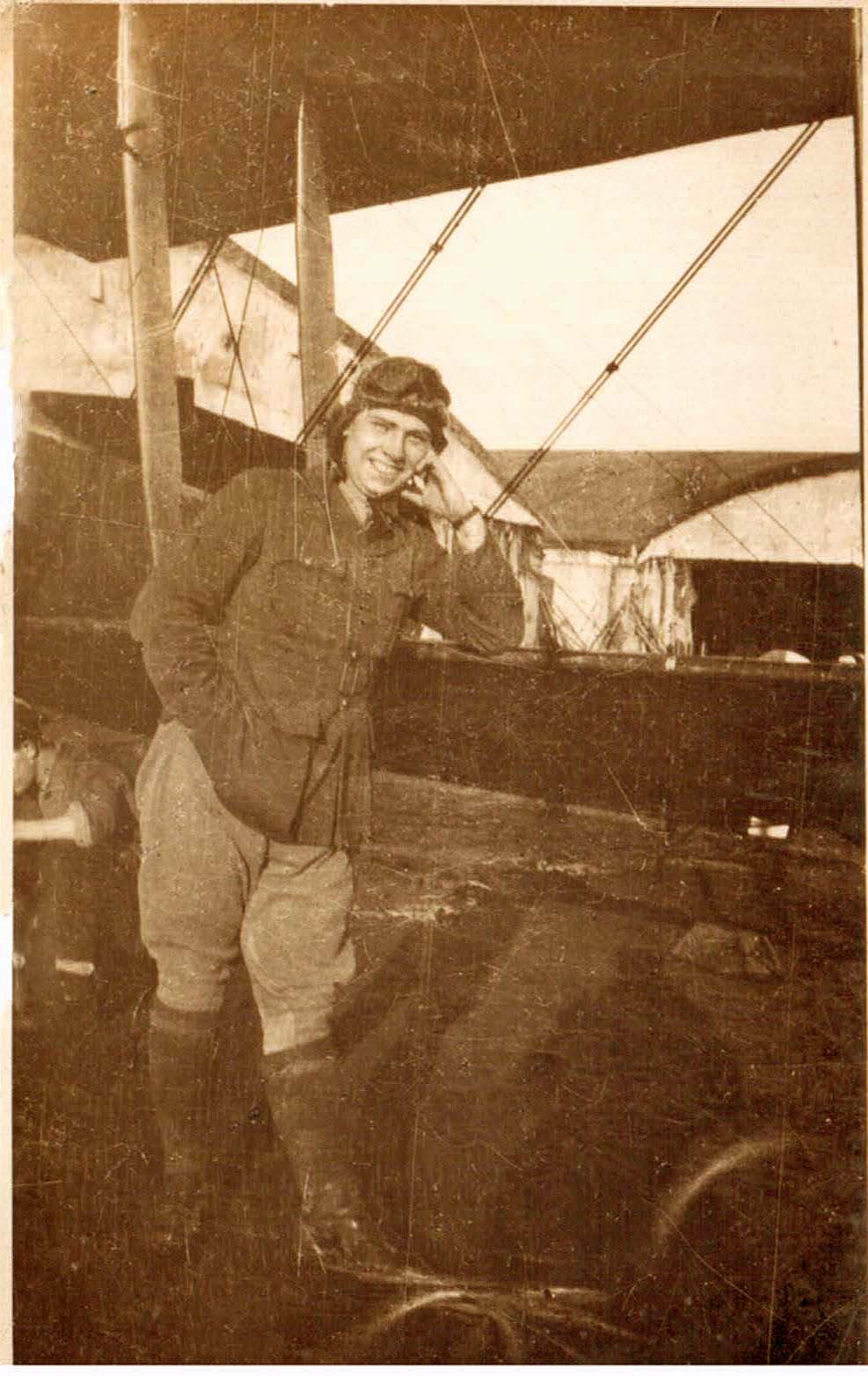

Major Petch in C1940

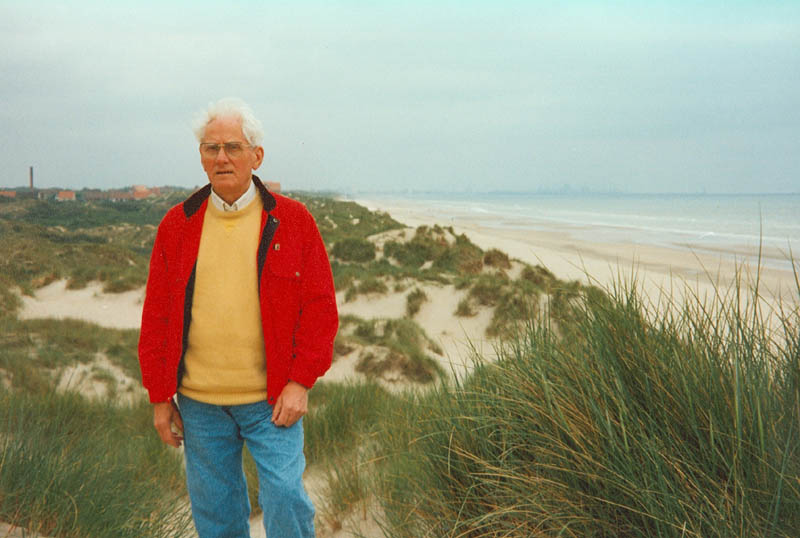

Major Petch in later years

Officers of 6 Green Howards 1944, around D-Day. Does anyone recognise any of these men? Please get in touch. Major Petch not shown

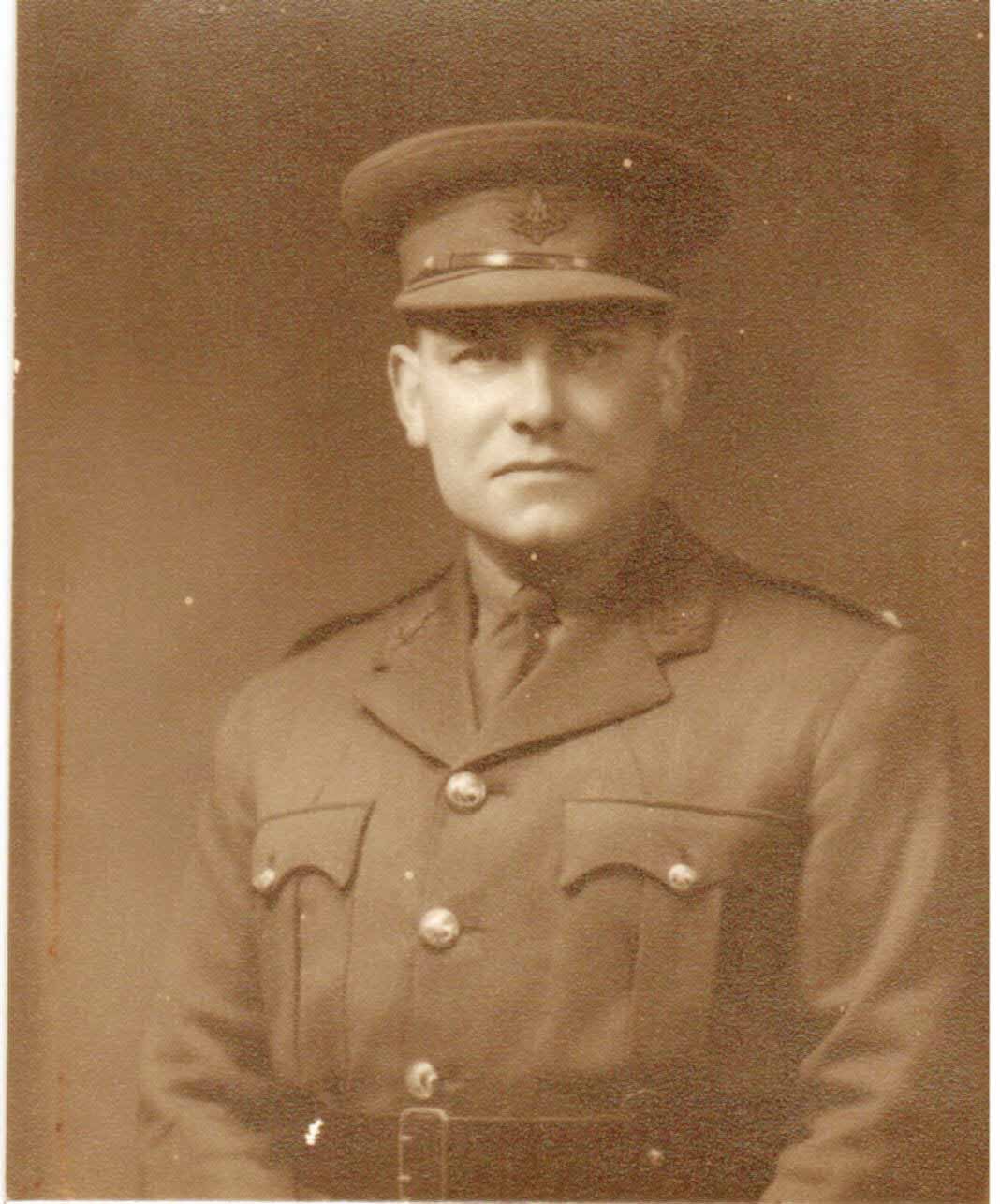

Postcard from Valliquerville, showing the "Au Point du Jour" hotel. Happier times before 10 May

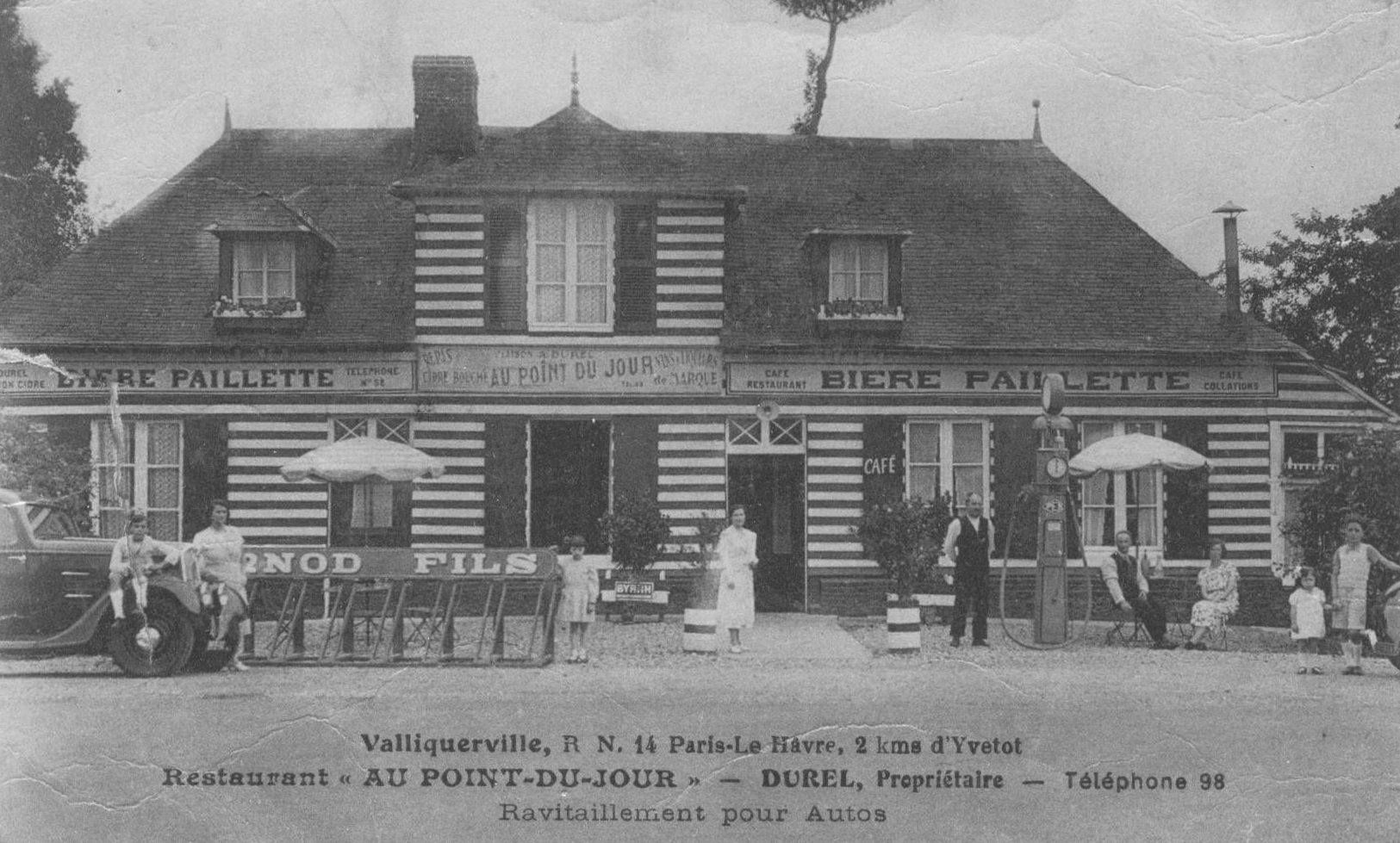

Brave 2nd Lt John Hewson, killed at Gravelines, buried at Longueness

The East Mole at Dunkirk where the troops boarded the Lady of Mann

The beach and sand dunes at Bray Dunes, Dunkirk some 5 miles distant.

Bill Cheall explores the sand dunes at Bray Dunes. C1994.

The beach and sand dunes at Bray Dunes, Carmichael had a lucky escape.

The beach from Redcar to Saltburn Major Petch's home area in Yorkshire. Bearing more than a passing resemblance to Bray Dunes!

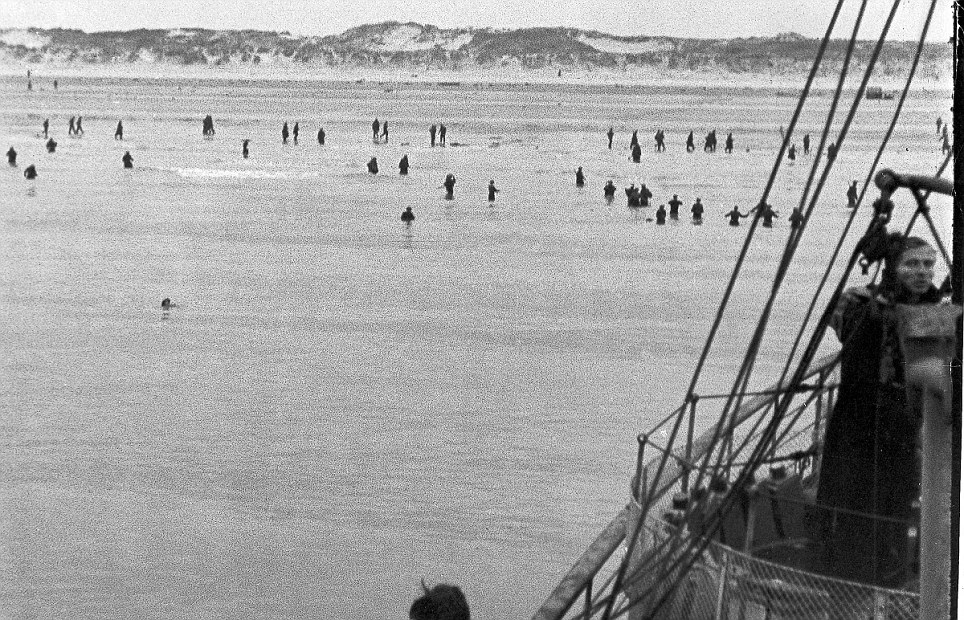

Soldiers in the sea at Bray Dunes, looking to be rescued.

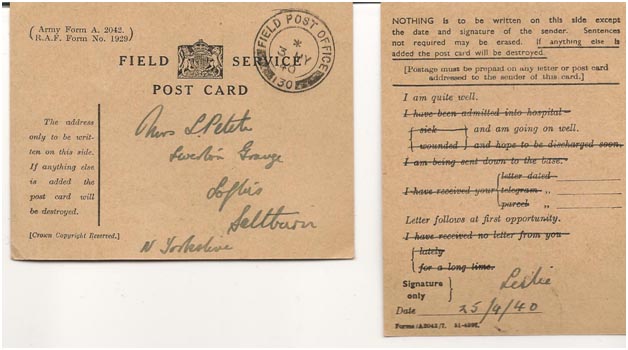

A letter home - soldiers couldn't always write an essay

Major Petch in WW1, in the Navy section of what is now the RAF.

After the war, Major Petch continued with a successful career in horse racing and presided over a number of northern racetracks with great success as manager, director or managing director, including Catterick, Redcar and York. In later years, he was awarded the OBE. Major Petch's connection with Catterick lasted 35 years, from 1948 until he passed away in 1983.

The Dunkirk Letters of Major Leslie Petch OBE – WW2 podcast - Show transcript

This is episode 9 in the ww2 podcast series

I’m Paul Cheall, son of Bill Cheall whose WW2 memoirs have been published by Pen and Sword – in FTFDTH.

The aim of these ww2 podcasts is to give you the stories behind the story – memoirs and reminiscences of veterans connected with Dad’s war in some way. I’ll be dipping into a different aspect of Dad’s memoirs every four weeks or so and if you’ve enjoyed what’s gone so far you’ll love what’s still to come.

And of course if you want to enjoy Dad’s full story, please buy the book. More details later.

This episode features the Dunkirk letters and memoirs of Major Leslie Petch OBE. Major Petch was commanding officer of 6 batt Green Howards, in 1940, WWII

Over the last few years I’ve spent a lot of time tracking down comrades of my Dad. I’ve hit a number of dead-ends doing this but I’ve also had several successes. And these include finding Major Petch’s grand-daughter through the Internet. This this led me to his daughter, Jill, who sent me an amazing set of papers relating to this pivotal period of the war.

My Dad was Major Petch’s batman and messenger during Dunkirk so it’s fascinating for me personally to hear another account of the events leading up to the evacuation, which was called Operation Dynamo. OK let’s get going my friends.

Just for starters I’d like to share with you a private note about Dunkirk that my Dad wrote for the family cos I think it’s a great scene setter for what’s to come. You, listeners, are the first people in the world to hear this:

Dad said …

"Although it will be very condensed, I will try to explain to you about Dunkirk, but first a few facts.

Winston Churchill was a brilliant man and for years, before the war, he had been warning the government that Germany was rearming and preparing for war, but his warnings fell on deaf ears. All Europe, except for Germany, was totally unprepared for war.

The men of our 23rd division, who were Territorial Reserves, had never done any training to turn us into fighting units. The same thing applied to other Territorial Army divisions. Belgium and Holland wanted to remain neutral so did not arm or prepare defences and would not allow our observers into their countries so as not to offend Germany.

Our divisions went to France early April 1940 as a labour division with the British Expeditionary Force (BEF). None of us had even fired a rifle. We prepared landing strips for the RAF. Now when the war really started and Hitler attacked on 10 May 1940, our only real plan was to push into Belgium when Germany crossed the frontier and that is what happened.

The Dutch were soon overrun and the Belgians capitulated soon after. British troops were moved anywhere to try and plug gaps along the front.

Our lot were constantly on the move, never in one place for more than two days. We soon got used to our weapons, trying to hold the German advance, but could never attack because we didn’t have the training or weapons. We just had to take all they threw at us and fired our rifles whenever we saw a grey uniform and square helmet! (Listeners can you just imagine that?!)

The enemy all along the front were most powerful and used what was described as blitzkrieg tactics. Their bombers would give our lads a good pasting and straight away the tanks would attack, followed by a well-armed infantry. It was the infantry we went for.

When the evacuation from Dunkirk first started, all non-combatants were lifted by ships off the beach straight away to avoid congestion, and as the perimeter became smaller, less well-trained soldiers made their way to the beaches, while the better-trained soldiers held off the enemy to enable the ships to get men away.

Without going into detail, from May 10 to 28 we were plugging gaps wherever we were sent to. Then we had to make our way to the beaches – being bombed and strafed all the way for 12 miles - and finally got away on 31 May.

Someday, you will have time to read my war books and only then will you fully understand why and how it all happened as it did.

If our army had not got away from Dunkirk, some 340,000 men would have been finished because England was very short of manpower and could not otherwise have taken the aggressive action we took as the war progressed.

Hope this has made it all a bit clearer for you.

Bill Cheall, 1994

Listener, bear in mind this podcast relates to the Green Howards, a Northern English regiment. A lot of the soldiers came from Middlesbrough in the English county of Yorkshire and surrounding area, including the Major’s seaside home town of Redcar, renowned for its horseracing. As a lad I remember running along the beach at Redcar with pals to keep fit. One time my friend lost the keys to my Dad’s car. If you go there today look out for a shop called Pacitto’s - it sells the best icecream in the world. And if you find my Dad’s keys in the sand there’s a free hardback copy of Dad’s book in it for you!

Major Petch wrote several letters home to his wife during the early days of the British Expeditionary Force (the BEF) and later, back in England, he also wrote a war diary describing the events. So these papers are what I’ve sorted through to give you the story.

The papers reveal a stark contrast between the early, heady, positive days of the WWII BEF and the hard, desperate times experienced during the fighting.

Major Petch’s unit, the 6th Battalion GH then part of the 23rd Northumbrian Division, initially went to France on 24 April 1940 to construct an airstrip, as part of the BEF

Remember that Britain and France had declared war on Germany in September 1939 so up to this point no land-based hostilities had taken place – this was the period of the so-called phoney war. Though there were various minor bombing raids and reconnaissance flights on both sides.

The letters begin just before the journey to France, when the troops are on the move in England. So these are from the Major to his wife. The Jill mentioned is the Major’s daughter. There are many other names mentioned and sadly we don’t know much about them. But if there are any relatives hearing their names please do write to me at Fightingthrough@yahoo.com

WW2 podcast letters:

Monday 17th April 1940 - Basingstoke

I have just seen to supper and to bed about 70 of my Company who had just arrived back from Middlesbrough by special train. There is a rumour we are getting a new Brigadier but don’t know who! The next rumour is that we move again on Wednesday to a place on the south coast some 5 miles East of Bournemouth.

Friday 21st April 1940

I was loath to leave you and Jill especially after a terrifying night. I had not realised before that you certainly do not like the German planes over. I had made up my mind to get you down here at once, but true to the Army, this morning we have just received orders to move tomorrow to 17 miles from Bournemouth to a military centre. It’s within 2 miles of the tank headquarters.

I’m very disappointed at the news. I got a train right through and arrived here about 10.15 p.m. Hope you had no air raid last night – they were at Billingham on Wednesday night. Will let you know as soon as I have news.

April 24th - Basingstoke – Southampton

I am writing this letter on the train. The ride is very bumpy – it’s not any drinks we’ve had, as there’s only tea on the train! We had 2 very enjoyable concerts last night and got all the Company on the train safely. I slept well until 8 a.m. three of us are in a compartment - Padre, Bolsover and self. I am looking forward to the journey as we are quite a jolly crowd and the journey is passing quickly so far.

There are 10 troop trains in front of us and we have 6000 mattresses for the Division. I hear it is somewhere near Arras where we are going in France. The plan is now we come back to England in July and our camp will evidently be not far from home.

All my love to you and Jill.

26th April - Valliquerville

Listeners the Major is about to talk about writing letters home – I need to give you a bit of background – When the men wrote home they were only able to talk about their life in the camp and could not mention where they were or what they were employed to do. So the officers had to censor all mail.

I am just recovering from beaucoup laughing! We have done a great many letters and as we censor them altogether in this local village pub – the mirth is not all due to the local vin blanc!

We had a good journey and no one was seasick. We are glad to have a rest and get into a good bed.

I slept 2 nights with my clothes on. The men are in a medium-sized village billeted in barns with straw on the floor. They are quite happy and are sorry it is only a temporary arrangement. We all went into the bigger village last night and 22 officers had dinner together.

Six of us are at a roadside pub and all are learning French quickly from the vivacious mademoiselle of about 16 years old. Richard Dorman is the best scholar, having spent several weeks with the French people. It is most amusing – I don’t think I have ever laughed so much in my life. One or two of the sergeants cannot speak a word of French and shout louder and louder at the local people who do not understand them at all!

We are having a really gay time and when we move on to meet the rest of the party, it should be good fun.

30th April WW2

The letters from the men to their girls are delightful, in fact after reading about another 200 a day, I have come to the conclusion I have a lot to learn in writing them! Many of the fellows say ‘absence makes the heart grow fonder’ and ‘east or west home is best’.

They are all promising to be true, especially as they think very little of the French girls in the village. The reason being that the Mayor has warned them all to keep well clear of the English Tommy!

The Padre lunched with the six of us and was introduced to our Mademoiselle Lu-Lu – he was quite taken with her! We all try out our French now and make some delightful howlers.

Harold Kidd at lunch today after having soup and roast beef etc sat back and declared ‘Je suis plein’ - which he thought was ‘ I am full’ actually he did not know it was the French idiom for ‘I am pregnant’!

All the water is condemned and the land is quite flat around here. I said at lunch I had not seen any running water at all. Harold Kidd said there must be a cistern in the room above as he heard water running for filling a cistern for about 5 minutes. When I told him Madam slept just above us, he coloured and the Padre laughed so much he couldn’t eat his fromage!

We are having very good food at this local pub. Mademoiselle has not served frogs since her grandmother died. We hear the bullfrogs croaking at night and the men say they also have rats at night to keep them company.

We had a church parade this morning near the Chateau where the local Mayor lives. It is a delightful place and so well kept. The parade was in the orchard and Lord Downe attended the service. There are lots of orchards in this district and all in full blossom and they look very attractive. It is just like summer and it was brilliantly hot yesterday.

We have a tip-top meal in the town every night and officially had the Mayor and Mayoress to dine with us. We did quite a bit of talking in French and in return six of us were asked to dine with them last night. They had nine courses and an equal number of different wines – I was not one of the party as I am not very fluent in French!

Did you go to the races yesterday? I hope you did and made a bit of money. I have not heard any racing news since leaving England. It seems a longish time but I am treating this as my summer holiday and intend enjoying myself.

Listeners, on 1 May, the troops were given notice to leave where they were staying:

May 1st British Expeditionary Force, WWII

I am sitting in a tent with Harold Kidd writing with the aid of a candle in a bottle and a hurricane lamp. It is 10 p.m. and we both felt we would like to drop a line to our wives. I certainly would love to have you here. I must just live on happy memories for some time.

After dinner tonight the Padre and I went for a walk right up on to our area and it began to thunder and lighten - it was a glorious sight. We ran and just beat the rain by the skin of our teeth and it is pattering away for all it is worth on the tent. We have got our tent frightfully comfortable – even boot rests. A shaving shelf is fixed on the tree and a large mirror above.

The country all round is just like summer and the cowslips are in abundance. The poplar trees are shady and the corn is growing and everything is peaceful and quiet.

We are all rested again after a night of travelling – my mother is usually about ½ an hour before a train time but the whole Battalion was 5 hours before the train arrived! However time does not seem to matter and we have the utmost difficulty in remembering the day or the date. It will be much worse as we are to work Sundays like an ordinary day.

I suppose my figure will be so elegant that you will envy my waist when we meet again. My girth is no less at present. If I get too thin, I am afraid Jill won’t know her ‘Dada’.

How are things going at home? I should just love to get into the car and peep in and see how you all are. Most of the men are looking forward to a mail from home – no one has had a letter yet.

We were all very sorry to leave our little pub by the wayside. Madam cried when we left and several of the young officers kissed Lu-Lu our vivacious young, French girl on both cheeks. Harold Kidd thought face in French would be cheeks and asked if he might be permitted to kiss her on both cheeks – the situation became rather embarrassing as face in French means bottom!

May 5th

I had a wonderful mail last night – two lovely long letters from you – thank you very much for all the news. I shall be delighted with the photos you’re sending – it’ll be some recompense for the long distance you are away from me. To add to a very good mail there were 2 Evening Gazettes and Northern Echos. It was quite refreshing to read about home news – the men were very pleased to read it too.

An extra point to cheer me up was an order that I need only go out to the work 2 days out of 3. After lunch today my Sunday’s afternoon nap has been most welcome.

Darling it does seem a long time before we’ll see each other - we will just have to interest ourselves in other things and hope the time passes quickly.

I think for your own reputation you should dissuade Baba from calling all the British Army Dada! Am glad she is very well, although I can see her inheriting the female liking of both families for Scarborough and little runs out in the car!

I have had a few talks to Lord Downe and a chat with Lord Gort the Commander in Chief the other afternoon.

The young fry were given from Saturday noon until Sunday noon leave – they took a car to town and stayed the night, dancing etc until 3 a.m. I have not felt like taking my days’ leave yet!

May 9th 1940.

Thank you ever so much for your letters, please give Baba a big kiss from her Dada for her first letter to me, or rather for the marks on the new note paper.

I am now looking forward to every mail and longing for the photos to arrive. Harold Kidd had a photo sent of his 10 m.o. baby boy and it is now on the bacon box in our tent, which is acting as a chest of drawers.

You apparently have only got my first ever letter written just after lunch with my Sub-Lieutenants either side of me, bombarding me with questions about censoring mail and handing me all the doubtful ones to sign! You are quite wrong about my drinking too much red wine’ – champagne and white wine are the only drinks I have touched!

By the way it was Rex’s birthday yesterday and to cheer us all up, when the working party got into the second dinner about 9 p.m. last night, there was a magnum of champagne for us to drink his health.

It is the unanimous decision of men and officers that the girls in this district are very unattractive, so as long as I am in camp there will be no counter attractions as regards the fascinating French girls!

Tuesday was my company’s day in camp to do odd jobs, so I took the opportunity to have my first day off. Jacques Leguise, our French Liaison Office, is a real good sport and speaks good English.

He and I took the shopping car into the fairly big town and had a most enjoyable day. We bought treacle, honey, marmalade, beer and wines and other provisions for the canteen, Sergeants’ Mess and Officers’ Mess.

Chickens at 70frs a piece for our dinner that evening and asparagus and French beans. We visited the N.A.F.F.I. and a large provision shop and after buying shaving mirrors, bulbs for torches and Rex’s hair cream and various other officers’ requirements we retired to the best hotel for a quarter bottle of champagne each - 12 fr. a time.

After just having one we went along to an Officers Mess and had a cheery chat to more English Officers whom Leguise knew. Some had just come back from a race meeting held in France and I was full of questions as to how to wangle it!

I saw a few war correspondents but did not recognise any racing reporters! We afterwards retired to a good café and had an excellent lunch – soup, Dover sole, and chicken etc and some Anjou white wine.

Feeling right on top of the world, we bought several very comfortable chairs for the Officers’ Mess and returned back to camp for tea. Podcast of WW2 story

It was gloriously hot and we were just having tea outside when the Dir. Gen. Herbert and Lord Downe and one or two more came and joined us for tea.

Richard Dorman and I have been having several chats to the old farmer who is working the land within 10 yards of our tent. He is quite interesting and told us all about his farm and cows and horses etc. There are lots of partridges but no game can be shot during wartime.

Some of the boys are sending lots of kisses by every letter and telling their girls to count them all up and they will deliver them when they return. Most letters have SWALK on them (Sealed With A Loving Kiss) and as I am the one that signs them and seals them up I have already sent hundreds of kisses to England. Nevertheless I have a lot left for you…!!

There is a dance in one of the local towns tonight but as Reveille is 5 a.m. and we have to be using our pick and shovel at 7.30 a.m. I don’t propose to go.

Yours for always, Leslie.

Listeners, the all the frivolity ended dramatically when the Germans invaded Holland on 10 May 1940 and the British braced themselves for heavy action. Major Petch wastes no time sending a quick letter home ..

May 11th 1940

I sent you a postcard this morning to say I was well, as now that the war has started properly I thought you might be anxious. No one knows but I think the general opinion is that the hotter it gets the sooner it will be over.

I felt quite bucked to be in France yesterday when we are facing a most critical time in our history. 5 a.m reveille on a Sunday morning and a hard day’s work in front, keeps your figure right.

Sunday May 13th evening

I am sorry I was unable to finish your letters on Friday, but I have had several interruptions and there has not been an opportunity until 7 p.m tonight. We are all getting used to little sleep and lots of work – I am sorry my letters may be a bit thin of news but if only I could write a bit more of our doings.

Pause …

It looks as if there will be no more racing for you for a bit – I am glad you insisted on the sand bags. Don’t let the raids worry you too much – you can take it from me they are not too bad.

Wish I could have had a weekend with you. I see today that it is a working day – it certainly is here!

Hey! Don’t ever think I get ‘sick of reading’ your letters – it is the mail we all look forward to!

Those who receive a letter, treasure it more than £1 notes! Harold Kidd has just shown me snaps he has received today of the 10 m.o and they are very good. I am longing for Baba’s photos and yours.

We all look marvellously fit and are quite brown. Some of the Officers are growing moustaches – I still have razor blades for my top lip!

Listeners – that’s the end of the Major’s letters from France – we now fast forward a couple of weeks to:

Sunday June 2nd 1940 – Hereford, England.

What follows is a pretty self-explanatory letter and clearly the Major is now back in England.

It was glorious to be able to ring you up and hear your voice again after about 3 weeks of the hardest time of my life. I intend this afternoon to write a diary of our movements and a few of our experiences; but for the present I have half an hour before I go to St. Martin’s Church, Hereford to thank God for our safe return. It is expected that as soon as we sort ourselves out we go on leave for a few days until the Divisions reform.

The Battalion has been split up and several casualties have occurred. John Harrison – from Nunthorpe was the first Officer to be killed at Gravelines where we knew that at least 15 men were killed. There were about another 50 which we have never heard of since May 24th. They include Harold Kidd and Peter Forster. John Middleditch, another Company Commander, was wounded and we now have lost Bill Richards.

We still hope Harold Kidd and Peter Forster etc might turn up although it is only a slender hope now. Peter Forster’s brother in the 4th Battalion was also killed and I hear Colonel Litteboy is missing. Lord Downe left us for England in the midst of our activities about the 21st May!

Listeners, you might like to know right now that records show that Harold Kidd and Peter Forster were actually taken prisoner at Gravelines but survived the war.

Among the things I have lost include 6lb in weight, every bit of my kit and uniform except my shaving kit and towel! I only have left what I stand in – breeches, leggings, battledress tunic and mackintosh! Nearly every officer in the battalion is the same.

I saw Barry Linton under immensely interesting circumstances! We were rushed up to the Canal du Nord to protect a bridge – I went forward to see who occupied it and there was Barry preparing to blow it up! His man told me afterwards he had fainted that evening and cracked his skull and was in Arras hospital the day before the Germans occupied the town. I don’t know any more. I am simply longing to see you and be with you again. I will wire immediately I have news.

Listeners - before looking at what happened next I’ll just pause for thought about the strength of the Allied forces amounted to compared with the German army. The whole BEF together with the French 1st Army came to around 400,000 men,

Most soldiers were armed with a Lee Enfield 303 rifle, a bayonet and a few hand grenades – that’s little different from the First World War. Each section would have one Bren gun. Within an entire company, there might be just one Sten gun.

There were a few anti-tank guns, but these were no match for Panzer armour. Tanks and armoured personnel carriers were few and far between.

The German army had more than twice the number of troops, and many individual soldiers had sub-machine guns. They also had more and much faster armoured vehicles (and that included the Panzer divisions).

The contrast in fire-power was stark.

Listeners as I said there were no more letters, but now he’s safe back in England, the Major sets about writing up some notes about his experience. There’s a slight overlap with the letters but I thought it best to preserve everything in its original form as far as possible for this ww2 podcast.

Hereford, England, June 3rd 1940

Here is a resume of my movements since leaving Stockton the 24th April. It certainly has been an experience and undoubtedly the hardest time of my life.

We had quite an uneventful crossing from Southampton to Le Havre, where we moved out some twenty-five miles to a rest camp at Valliquerville.

The men were billeted in barns from April 26th – 30th and it was here we saw the best of the visit to France.

The Battalion Orderly Room was in a Chateau – well kept and occupied by the Mayor of Yvetot. We entertained the Mayor to dinner together with his wife who wore brilliant diamonds. They in return reciprocated and served a nine-course meal with a wine dinner in their Chateau.

The brightest part of Yvetot was nevertheless the ‘Au point-du-Jour’ a homely wayside hotel with a vivacious and pretty French girl called Lu-Lu who kept all the Officers of A and B Companies alive and did a good deal of cooking for us. I am afraid there were several tears shed by the junior officers when we left there.

It was 8.30 p.m. on the 30th April when we marched off to the station and as the proverbial French rail system lived up to its name, the train arrived at 2 a.m. We travelled through Amiens on to Albert and then on to Miramont station. We disembarked and marched 2 miles to a poplar wood where we pitched our tents. It was on the site of the old battlefield of the Somme – many shells and various relics of the last war remained. Rex knew this area quite well having fought on the same ground some 24 years previously.

May 1st .......

We started out to build our aerodrome at Gravelines some 2 miles away. Gravelines wood was very famous in the last war – it was taken and lost 8 times by the French. All the local inhabitants avoid the wood as they say there are 20,000 ghosts there – the number of Frenchmen who lost their lives in it. The shell craters and the tree stumps with shells embedded still remain. The young trees are grown up but none are more than 20 years old.

The aerodrome was a grand place and we all worked hard to get it completed. The 5th East Yorks and us worked in 12 hour shifts. The great long concrete runways were nearing completion by May 10th. The Major in charge of the engineers was a Major Nuttall – the great contractors, and he brought nearly all his workmen to build this aerodrome.

We had 4 or 5 air raid warnings on the night of May 9-10 and at 5 a.m. the first air raid took place. 10 engineers were killed and 40 wounded. We carried on with all speed and hoped to finish the aerodrome in a week or so. That evening 9 Hurricane fighters landed on the aerodrome from Nottingham.

They had tried to reach Lille but owing to fading light landed with us. I took one officer into my tent and shared blankets etc. However at 1.30 a.m. I was ordered to collect the whole of my Company and rush off in cars with no lights to Albert to defend the Air Factory against the sabotage of a body of parachutists who had just landed nearby.

At 3 a.m. I arrived at Albert, which was about 10 miles from the camp and studied the maps and private defences of the French Officers – they spoke no English and appointed me to be responsible for the defence of the factory.

After placing my men in position in the few trenches and dug-outs I took a Bren gun and a reconnaissance party out by car to locate these parachutists and after chasing several French workmen in the grey light of dawn returned to the factory.

After a couple of hours after dawn the French relieved us and we returned empty-handed back to camp.

Another few days of air raids in the district and constantly standing to, led us to our departure from the camp at Arles on May 16th [Listeners, out of interest, 17th is when Dad became Major Petch’s batman – I’m not sure why the post became vacant].

That day was the last of any letters received from England. They were dated May 10th.

Listeners subsequently, the unit was to engage in many actions against the enemy which

sometimes resulted in casualties but at other times proved to the Germans that the

British soldier was no walkover

We rushed to Marquion on the Cambrai–Arras road and held the Canal du Nord. Thousands of refugees formed a pitiful spectacle as they proceeded wearily away from the Hun onslaught.

Listeners, my dad, described this in his own memoirs:

‘Old men, women and children were pushing anything on wheels – bicycles, prams, barrows – anything to save carrying more than they had to. Then suddenly out of the beautiful blue sky came the planes making a beeline for the poor folk, machine-gunning everything. Dead bodies lay everywhere. Distraught children, not being able to understand, lying across dead mothers.

I recall watching an old man and woman who, upon seeing the bullets making a path along the road, put their arms around each other and they both fell dead.’

Back to the Major …

The petrol dump at Douai had been burning for days and the whole scene was one of desolation as we went forward.

Having taken up a position on the canal by dusk and guarded the 3 main bridges we stood to all night expecting an attack, which did not take place. The morning of the 17th we were subjected to bombing a few yards to our rear and to our right.

The engineers blew up the bridges and we retired at 9 p.m. to Rumaucort. The tanks had scattered. We marched to Brigade H.O. at Dury some two miles further on. Then at 2 a.m. we arrived at Saudemont and took up an all round defence near the local woods.

It was here we helped an English woman and her daughter and sent them on by our transport. They were from Lens – the girls address was Miss N Caudron c/o Miss Pendry, Palmers Green, London. Listeners I wonder where they or their descendants are today?!

At 9.30 p.m. of the 20th May we marched some 10 miles with instructions to pick up transport to take us to Thelus.

The German mechanised column had moved quickly from Cambrai to Arras and as much of the Battalion as could be recalled were ordered to take up a position on the Scarpe some 5 miles east of Arras.

A great many roads were in chaos and roadblocks were in abundance to stop the German tanks, which were reported on nearly every road. After many detours we found ourselves about 10 miles along the Arras - Cambrai road and I took charge of the column and raced back to Arras, which was subjected to a violent air bombardment.

We got past the tank traps and mines, past the burning station in Arras and at dawn emerged on the Lens side of the town only to be machine-gunned by German planes.

Listeners I’m leaving all these place names in the narrative deliberately because it helps paint the picture of just how frantic and uncertain it all was. If you want to see a map of the whole set-up you’ll find Major Petch’s originals in the ww2 podcast shownotes at FTP.co.uk

Thelus – on the Vimy Ridge (5 miles north of Arras) was our objective and as we arrived there more bombs and machine gun bullets greeted us. It was now 5 a.m. and the message awaiting us, was to take a position on the Scarpe and hold it for 24 hours. This was about 10 miles away.

We rushed there and took up position in the woods. We saw the Germans attacking Arras and after the town fell about 11 a.m. they turned their attention on to us.

Being subjected to bombardments and having conferences at midnight and 2.30 a.m. we, with the aid of a Company of 7th Green Howards under Archie Scott, held the line until relieved by the Wiltshires and the 50 Division at 8 a.m. on the 21st. It was here we suffered our first casualties - about 10 wounded chiefly by trench mortars.

Back to Thelus – some 20 miles we marched and arrived about noon and took cover in the woods. All the afternoon we were subjected to some 50 enemy planes bombing and machine-gunning us.

At 6 p.m. the Division had little food, so the Brigadier instructed me to get and kill and have ready for the stew pot some 40cwt of beef. As I was driving some cattle into a yard to be slaughtered the Hun planes thought we were good meat and again gave us a warm reception. I dived into a nettle bed and some went up my nose and my face was very red with the rash!

Getting back – there was another flap – a number of enemy tanks were in our rear and we had to move at 9.30 p.m. to Seclin in the Lille area. Our Brigadier disappeared after Thelus! Arriving at Seclin at dawn we had to fortify the position and open cellars up – cave in French. WW2 history podcast.

All houses seem to have wine cellars and most have wine in them. Everywhere we went all houses had been evacuated and only the animals remained. Birds in cages, rabbits in boxes, cattle in the farms – and all the cows waiting to be milked. Everyone had just rushed off and scarcely taken a thing.

We broke into these places and sustained ourselves with the vintage of the land. Some of the men knew how to milk. They had scrambled eggs, milk and champagne for supper!

It was 9.30 p.m. again on 22nd May. Just as we hoped for a sleep, that news came through that the Germans were advancing rapidly on Dunkirk and that we were to be rushed to Gravelines some 10 miles west of Dunkirk. Our battalion was the only one to get through.

May 24th.

We arrived at Gravelines about 10 a.m. and found some French in position behind the canals which run nearly all round the town.

Listeners, my Dad’s memoirs again provide some detail about this:

‘Gravelines was almost surrounded on three sides and there was a tremendous battle raging there. It seemed ages since we had slept or eaten. Our company commander, Major Petch, was a tower of strength to us all and I could almost feel him suffering inwardly for the safety of his lads.’

It was in the evening that a sniping commenced but at dawn the battle really started. A batch of refugees attempted to rush the bridge followed by three German tanks. We fired on the tanks and fortunately stopped the rushing of the bridge. It was here that John Hewson fired an anti-tank rifle and stopped 2 tanks with it. But he was then hit by a mortar and killed

Listeners My dad describes what happened next:

‘The German infantry who accompanied the tanks made a show of making an attack upon us and we retaliated aggressively, killing many of them and causing them to withdraw. We were so incensed over the death of our brave young officer!’

Major ..

We were shelled intermittently all day but held out until dark when the French relieved us. During the heat of the battle I sent 2 anti-tank rifles to help Bill Richards - and Athwaite did good work before being wounded while retiring across a small canal.

What saved the day was the 3 English tanks, which supported us. They came out of the fight with 2 wounded in the cruiser tank, nearly all their 2” ammunition gone and their Vickers machine gun out of action for lack of water and ammunition.

The Tank Commander seeing some of the French running said it was impossible to hold out much longer and he was retiring to Dunkirk. After giving him a drink and food, taking his wounded to hospital, and also supplying men for his gun and getting them working did I prevail on him to return and at least give us moral support.

After another hour the attacks died down and we were ordered to march to Fort Mardyk just outside Dunkirk. 25 Hun planes straffed us as we came out.

Arriving at Fort Mardyk we slept for a couple of hours before taking a further defensive position. There were several of the Battalion left at Gravelines. 14 were known to be dead and 30 were and still are missing. At midnight of the 25th we went to Les Mores and on the 26th we marched 6 hours from 3 p.m. to do traffic control south of Bergues.

Listeners, my Dad in his memoir said about all this - Considering our strength, we had put up a good show against a very forceful enemy who knew that he had the upper hand.

For the action we fought at Gravelines, several officers received decorations including our Lieutenant Colonel Steel who received a bar to his DSO and we were mentioned by name in the despatches of Lord Gort.

Each order to move took us closer and it became obvious that many of us would be killed or captured, and right now we felt very tired, hungry and dirty.

Comradeship was at a premium and its values had surfaced on many occasions during the past weeks. Our company commander, Major Leslie Petch, amazed me. I was still batman and runner and I risked my life many times taking messages to the other companies, but more often to Battalion HQ.

I, more than anybody else in the company, saw the personal side of him. He was a brick and a tower of strength, setting an example to every one of us by his stoical character. He was overflowing with determination and always retained his gentlemanly attitude.

Many times I saw him sitting on a wall or rock, or just sitting on the ground, staring and thinking, giving me the impression that he was silently praying for his lads. I would say, ‘I’ll go and see if I can scrounge a mess tin of tea, shall I, sir?’ Wherever we halted there was always some lad whose first thought was a brew, and somehow he always managed it.

His reply would always be, ‘That would be grand, Cheall, but you must not take any risks, we can all have as much tea as we want when we get back to England, and we will get back, God is watching over us.

Back to the Major …

After just getting into position and diverting all lorries etc into a large park we received instructions to march back to Teteghem (Taytergem) where we arrived at 3 a.m.

The men had had practically no food for 24 hours nor could any be found until noon on May 28 - it was tinned herrings and biscuits – a few men got a drink of milk at the farm house which was being evacuated.

At 1.30 p.m. we received an urgent message to march some 15 miles to Haeghe Meulen and protect the flank of the B.E.F retiring on to Bergues. We had been told that we should be evacuated that day from the sands at Dunkirk and it was a great disappointment to the men who were now practically exhausted.

One of my platoons under Claude Hull was lost in the night.

Many of the remainder of the Company fell out through exhaustion and only 37 out my original 100 faced the enemy and held their flank.

The shelling was much heavier than at any previous position and the main road was littered with casualties of the Lille area and troops rushing to Bergues and then on to Dunkirk.

Claude Hull returned - but not his men.

After 24 hours we marched to Bray Dunes arriving on sands about 3 a.m. on May 30th after a six hour trek. It was a long tiring march but everyone was more cheerful. There were thousands of lorries and every kind of transport dumped and all officer’s kit was left behind the canal.

Thousands of troops were on the 6 miles of beach between Bray Dunes and Dunkirk and I could have left with the 37 of my Company immediately, but decided to join the rest of the Battalion further on.

Carmichael and a few others went on a raft and reached the boats. Bill Richards and part of C Company also went on small boats to the larger ones. The small boats were abandoned and no one brought them back for further transport of troops.

Consequently for another day we hid in the sand dunes hoping for a raft or boat to appear.

Carmichael later told us that all the men dug out holes in the sand to hide from the bombing of the German planes. They dug one for him but when he arrived two young frightened solders from another Battalion were hiding in it and he said that they could stay there and he would go over the dune. Sadly a mortar landed in the hole and they were both killed.

As Beach Control Officer and seeing there was little chance of getting away from the shore, I took a car to Bray Dunes and found General Herbert. I then motored him 6 miles along a soft sand shore littered with wreckage on to Dunkirk and motored along the Mole to find out that we could embark there in the afternoon.

We were spasmodically being shelled and the 7th Battalion lost 10 killed and 100 wounded in embarking.

Pause …

It was 5 p.m. on May 31st when the Lady of Mann carried us out to sea with bombs dropping a bit too close. Two planes were shot down and 2 parachutists were floating slowly down to the shore.

The Lady of Mann was the ship that originally took us across to France and she brought us safely back to Folkestone and then on we came to Hereford.

Pause …

Listeners, in an epilogue to his diary, once again retaining his sense of humour, Major Petch added the following anecdotes:

There was considerable confusion throughout the campaign with the enemy tanks continually getting round to our rear. One night our transport Sgt. got lost and knocked on the door of a tank to ask the way. A Hun opened the door – our Sgt fled on his bike unharmed.

(Episode 9 in war history podcast)

At Albert one of my L/C told a rough reservist in my Company to go into a dark dugout and see if any Hun was there. The reservist in a polite manner unknown to him before said ‘after you, Corporal!’

It was surprising considering some of us only got 1 hour sleep a day for 5 days and probably one meal a deal of biscuits and bully beef that we remained so fit. But at the end of the campaign our feet were very tired and our legs moved slowly. After a few days rest at Hereford however we were all really fit and well again.

Pause …

Listeners, Dunkirk saw the end of Major Petch's war. Whilst stationed in the south of England after Dunkirk, he one day advised the troops that he would be leaving. He shook my Dad's hand before he left and said:

‘Goodbye, Cheall, and thank you, I will always remember the Company.’

As the Major left his beloved men, B Company also vacated its position on the coast. It had been a pleasant interlude and not a bit boring, as life in the army so often was in the future.

Major Petch's daughter, Jill, advised:

"My Father was discharged from the Army on medical grounds as his hearing was impaired after the noise of the guns at Dunkirk. This greatly disappointed him. He had been in the 1st World War in the Navy section of what is now the RAF and was then part of the Navy. In fact he is the only person I know who has served in all three Services. "

After the war, Major Petch continued with a successful career in horse racing and presided over a number of northern racetracks with great success as manager, director or managing director, including Catterick, Redcar and York. In later years, he was awarded the OBE. Major Petch's connection with Catterick lasted 35 years, from 1948 until he passed away in 1983.

In his own memoir Dad mentions the respect the men had for the Major. Dad described Major Petch as ‘a good, kindly man and I enjoyed attending to his needs. He adored his B Company and looking after him gave me much pleasure. He really was a gentleman and never forgot that the lads were human beings as well as soldiers’.

After Dunkirk, my dad, Bill Cheall continued to fight for the entire war. His next move was to North Africa, courtesy of the Queen Mary, to be part of Monty’s Eighth Army. After eventual victory in Tunisia, the Sicily invasion followed. Along with a number of other battle-hardened units, the Green Howards were ordered back to England to form the vanguard of the

Normandy Invasion.

In the fierce fighting that followed the D-Day landing on Gold Beach, he was wounded and evacuated. His comrade, Sergeant Major Stan Hollis, won the only VC to be awarded on 6 June 1944. After recovering, Bill returned to the war zone and he finished the war as a Regimental Policeman of the East Lancashire Regiment in devastated occupied Germany. For all this he earned seven medals and a wounded-in-action stripe.

He was discharged in January 1946 and returned to working in his grocer’s shop on Ann Street, Southbank, where ‘Billy Shields’ was a popular character until he retired in 1982. He was an active singer with Redcar and Teesside Operatic Societies in later years. He passed away peacefully in 1999 after a long fight with prostate cancer.

If you fancy buying the ww2 war history book FTFDTH go to FTP.co.uk and you’ll find a link. Amazon, Pen and Sword direct, Kindle etc etc. There’s also a discount code you can quote for Pen and Sword.

And there’s loads more in Dad’s book about the Dunkirk adventure.

I cried when I finished typing it – Sarah the typist

Lifting – Patrick

Loads of five star reviews on amazon

Now, listeners, I’ve got a few little postscripts for you …

Lt Hewson – it was Lt John McColvin Hewson who lost his life after bravely shooting up the tanks at Gravelines. When I went to France recently I took time out to visit the cemetery at LONGUENESSE where he was buried and paid my respects at his grave. He’s the only comrade that Dad mentioned who is buried there so he was somewhat alone. You can see the photo of his gravestone on the web site. I read out the story of his bravery as I stood in front of his grave.

I also went to the war cemetery at Hinges to see the grave of a friend Rodney’s distant cousin. I thought I’d gone mainly for his benefit but little did I realise that I had actually gone for myself too because there was quite a remarkable revelation when we got to the cemetery. There were about 30-40 graves, all in a neatly tended row, of British soldiers who were killed during the latter stages of Dunkirk and who were defending the withdrawal.

So indirectly my dad owed his life to them because they gave their lives buying time for the lads who got to the beaches. Never mind indirectly – directly is a better word. I understand that some of the fighting that took place was real vicious street fighting stuff – evidently they would defend a village or road junction to hold the Germans up, and when they couldn’t hold it any more they would run like heck and retreat to another defensive position.

And both Rodney’s cousin and in fact his father as part of the Royal Norfolk Regiment were involved with this, together with the Scot’s guards. So good on all you boys – thank you. I actually did a periscope vid from Hinges – if you want to see the graves and my commentary, you know where to look – FTP …!

And if you want to see the beach at Bray Dunes, I recently did a periscope broadcast during my visit to France. You’ll find it on the web site too!

And hey – if you’re listening to this in June 2017 aren’t you lucky – Dunkirk the movie is coming out in July!!! And if it’s June 2027 then hard luck - you’re ten years too late to see the premiere – but no doubt you can get a good deal on a DVD! If not then buy my Dad’s book if you can still get it.

Next episode:

We must go back again. Every one of those men in the water is somebody's son

Captain Tom Woods OBE, Dunkirk 1940

German planes were coming over, their bombs dropping the other side of the pier about 40 yards from us and we had seven holes made in the starboard bow close to the water line, also three lifeboats holed by flying shrapnel from the shells, several soldiers marching down were killed about 30 yards ahead of us in the wharf from the shellfire.

The ship was a ferry ship called The Lady of Mann (how could I forget that name?). How lucky we considered ourselves to be; out of all those thousands of men, we were being given the opportunity to be evacuated." Bill Cheall, 6 GH.

The memoirs of Capt Tom Woods OBE will be featured in my next podcast and it’s going to be a corker. He sailed the ship which rescued Major Petch and his men from the bomb-blasted beaches of Bray Dunes.

For more info on everything, including photos, social media links and easy subscribe buttons, go to ftp.co.uk.

I really hope you enjoyed this podcast as much as I did.

If you want to keep up to date, keep subscribed my friends. I’m playing out with my new outro theme tune and it’s called In Victory – I hope you like it.

This was episode 9 in the ww2 history podcast series

Featured Episodes

If you're going to binge, best start at No 1, Dunkirk, the most popular episode of all. Welcome! Paul.

PS. Just swipe left to browse if you're on mobile.