40 Four Brits & a Frenchman at Dunkirk plus Gallipoli - memoirs

Great revelations about Dunkirk war heroes. How one man's sacrifice saved the lives of possibly thousands of others.

More great unpublished history - of the Second World War.

The extraordinary turns of events that brought four Brits to the shores of Dunkirk at the same time as a Frenchman.

How one man's sacrifice - Fred Gardiner - saved the lives of possibly thousands of others.

The remarkable story of Maurice Bourel and his escape on the Lady of Mann and the battles he fought after that.

L'histoire incroyable de Maurice Bourel

Vivez les Francais!

Congratulations to listener Helen Westbrook for winning a prestigious story competition with her story and the same one that you’ve heard on the FT podcast!

Find out how Fred Reynard, hero of WW1 battle of Gallipoli escaped death two years before his WW1 adventures even began, in a jaw-dropping twist of fate.

Hear about the extraordinary turns of events that brought four Brits to the shores of Dunkirk at the same time as a Frenchman

The story of hero Fred Gardiner of the Kings’s Royal Rifles who died as part of the brave Dunkirk rear guard

Listen to Bill Cheall’s description of the terrifying havoc as his battalion escaped to the Dunkirk beaches. “We looked a very sorry sight, covered in dirt and grime, with hunger gnawing at our bellies

Fred Bates interview on YouTube -

Link to feedback/reviews at Apple Podcasts - Thank you.

Interested in Bill Cheall's book? Link here for more information.

Fighting Through from Dunkirk to Hamburg, hardback, paperback and Kindle etc.

Congratulations to listener Helen Westbrook for winning a prestigious story competition with her story and the same one that you’ve heard on the Fighting Through podcast! All about her hero grandfather, Fred Reynard, at Gallipoi - Dare you to listen! See link above to the There But Not There campaign where you can purchase a Tommy figure for your home to remember the fallen and help raise funds for veterans' charities today.

Fred Gardiner of C Company, 8th King's Own regiment. Died fighting bravely as part of the rear giuard defending a junction at Les Moeres near Dunkirk.

Map showing Les Moeres, where 40 Kings Own soldiers were killed by a Junker bomber.

Brave Frenchman Maurice Bourell received the French "Légion d'Honneur" medal in 1982

London, in front the Carlton Gardens, the headquarters of General de Gaulle in 1941. Maurice was part of De Gaulle's guard)

Libya in 1943 after taking Umm-el-Araneb with the troop of Colonnel Leclerc. Maurice is at the top left.

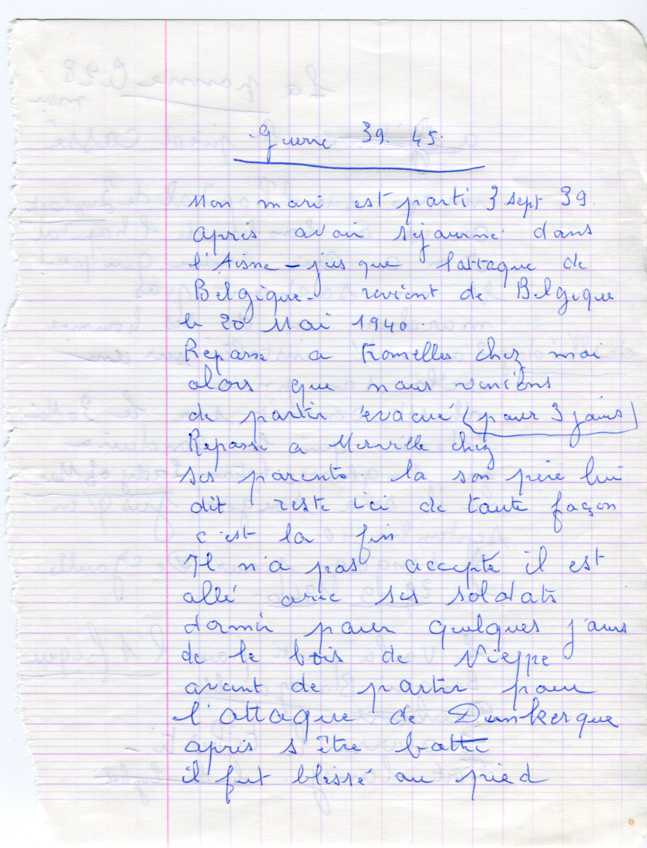

Grandma Bourel's notes on husband Maurice's adventures at Dunkirk (French). Click to enlarge.

Southport Hospital on August 20, 1940. Maurice bottom right. It would be fabulous to identify other people in the photo. I just know that he had befriended two Australian nurses whose family had moved to Southport. The nurse near him on the photo is Francis (Croack - Walsh?).

Lady of Mann

"The Magnificent Three" of the Dunkirk heroes of the Bee. Fred Reynard, engineer, on the left - he wrote about their adventure. Bill Trowbridge, skipper, in the middle. Harry Downer, mate, on the right. The young lad is Ernest (Muddy) Downer! The crane on the left still stands today on Newport Quay, Isle of Wight. Marc Hocking, aged 18, as fourth hand, not present.

Albert Sanger and wife Amy. Below, grandson Mike Wills

Harry Trowbridge, killed at Gallipoli and below his brother Bill Trowbridge who became skipper of the Bee at Dunkirk, WWII

Fred Reynard, avoided the Titanic disaster to then survive Gallipoli to become engineer on the Bee at Dunkirk WW2. What a legend!

Fred with wife Ada

Andy Nanos from Australia:

Selection of his War re-enactment photos

Brownie pic France and Belgium 2018, WW2 WW1 reinactment 1

Fighting Through Podcast - Episode 40 - Four Brits and a Frenchman

at Dunkirk, Gallipoli

More great unpublished history!

WW2

WWII

….

Hello again

I’m Paul Cheall, son of Bill Cheall whose WW2 memoirs have been published by Pen and Sword – in FTFDTH.

My dad fought at Dunkirk, North Africa, Sicily, D-day and Germany.

The aim of the Fighting Through Podcast is to give you the stories behind the story. You’ll hear memoirs and memories of veterans connected to Dad’s war in some way – and much more. All Great Unpublished History. WW2 and WWII history podcast

I do try to make every episode of this podcast standalone, so you don’t need to have heard every episode to be able to follow the rest and on this occasion the same applies. But I do think if you HAVE listened to some of the earlier Dunkirk episodes then you WILL gain more enjoyment from this episode, because you’ll be a little more familiar with the background, and that will somehow help you to enjoy this episode just that little bit more.

So I’d recommend you take a shufty at episode one for starters which also happens to be the most popular one. It’s a building block for the show because it’s about my Dad’s awful experience on the beaches at Dunkirk and how he’s eventually rescued. I’ll now carry on with this episode.

TRANSITION

1 Mum

To begin, I need to share some rather sad news with you. I’m very sorry to say that my Mum, Anne, passed away on 28 December, 2018, at the age of 96.

Her last days were comfortable but she struggled with pneumonia – and thankfully, she passed away peacefully in her sleep. My sister and I both saw her at length every day in the lead up so we still had some quality times, despite her illness.

I’ve received too many tributes to mention, but here are just a few of the sentiments from people who knew her:

Such a wonderful lady, a very special friend, such a gentle personality, always polite, great sense of humour.

And of course

if you’re a regular listener you’ll recall that my Mum featured in a few episodes of the Fighting Through Podcast, such as episode 32, Women at War, when she recalled what it was like being a young civilian in WW2.

So I’m so pleased she was able to share some of her wartime memories with us in that way as a permanent reminder of that challenging period in world history.

And what fun it was for her to play her part in producing the show - I received a lot of positive feedback from listeners about her episodes.

This week’s PS at the end of the show is, predictably, a short tribute to Mum, with some of her best, most poignant memories, so fittingly, of Dunkirk 1940.

So thank you Mum. Love you so much.

TRANSITION

Moving On

I’ve got several new Dunkirk stories to share with you today and the way they overlap is uncanny. They involve a death, an injury and an escape from Dunkirk in 1940. And the participants are four Brits and a Frenchman – hence the title of the episode. And I can barely wait to share the Frenchman’s story with you.

I’ve got a hat full of other short stories too. Now I know from my recent survey that around 40% of you listen to the show whilst at work and a similar number whilst driving. So if you’re driving whilst you listen, hold on tight to your steering wheel! And if you listen at work – you take care too, especially if you’re operating machinery or the boss is standing right behind you!

Enjoy

I‘ve got a one-off story to start off with.

2 This is the story of Harry Trowbridge - WW1

My first Dunkirk little ship episode – no 11 – came from Mr Michael Wills and featured Fred Reynard, the engineer on board The Bee.

And since then we’ve heard from Helen Westbrook who was Fred’s granddaughter and she sent me a fuller version of Fred’s account of Dunkirk, so WE HAVE two accounts of the adventures of little ship the Bee.

Helen also sent me Fred’s riveting WWI Gallipoli memoir.

Now here’s another story from Michael Wills about his Grandfather, and it’s about someone else who has a connection with Gallipoli …

and who also sailed on the Bee!

“At the outbreak of the First World War in 1914, my grandfather Albert Sanger had a girlfriend Amy Trowbridge. She had a brother Harry. Albert and Harry Trowbridge decided to join the queue of volunteers at Newport, Isle of Wight, Drill Hall.

Albert, 21, was a miller and Harry, aged 17, was a butcher’s errand boy. Both were enlisted to the Isle of Wight Rifles, an infantry regiment which was part of the Hampshire Regiment [Hampshire is located on the South coast of England, close to Southampton and a stone’s throw from the Isle of Wight]

On 30 July 1915, and after training, along with seven or eight thousand other men, they embarked on the liner Aquitania in Liverpool docks. The troop ship had two escorting destroyers to protect against German submarines. But the weather was so bad, the escorts had to return to port. The Aquitania took a long detour out into the Atlantic to avoid the U-boats. On 8th August, the “Rifles” were landed in the Dardanelles, Turkey.

Most of the men from the Isle of Wight were not to see England again for over two years. A large proportion, including Harry Trowbridge, were never to return. After a terrible mauling during the fighting at Suvla Bay, most of the Battalion were shipped to Alexandria in Egypt.

Harry’s body was never identified, but he is remembered on the memorial at Helios, not far from the site of the battle. Albert, wounded in the fighting, was repatriated to England. There he married Amy before being shipped to Alexandria, to re-join his battalion in autumn 1916.

The Isle of Wight Rifles were encamped by the Pyramids of Giza and then moved on to a deployment at the Bitter lakes, by the Suez Canal. By then, the remaining raw recruits of 1914 were hardened soldiers, but nevertheless the territory through which they were fighting took its toll. The regimental diary tells of snakes, scorpions, sand storms and extreme heat.

In January 1917, they marched first to Mazar and then in February they began chasing the retreating Turkish army across the Sinai Desert. The 145 mile march across the desert to El Arish took twelve days.

On the 17th April 1917, the offensive against the Turkish line at Gaza began. On the morning of 19th April, the “Rifles” led the attack against the Sihan Redoubt.

The Redoubt was captured, but at the roll call at the end of the day, of the 800 men who went into action,

only 2 officers and 90 men were recorded. And among those who did not respond to the roll call was Albert.

After the capture of Jerusalem, one of Albert’s mates returned to the scene of the battle of Sihan Redoubt. He found Albert’s army paybook and tatters of uniform still on the barbed wire of the Turkish line. The paybook, which soldiers usually kept in their left-hand breast pocket, had a bayonet hole through it and was soaked in blood.

Meaning well, Albert’s mate sent a letter to my grandmother [Amy] telling her of the circumstances of Albert’s death and enclosing the paybook. She kept it until her death in 1941.

What Albert was never to know was that he had a daughter, Molly, who was born in March 1917 - my mother.

Mike’s grandfather, Corporal Albert Sanger’s, grave and many others of the men of 1st Battalion Isle of Wight Rifles, are in the war cemetery in Gaza, Palestine.

A huge thanks to Michael for sharing Albert and Harry's story. I think it’s right up there amongst other poignant tales we’ve heard in this show.

But this isn’t really the end of the story, because Harry Trowbridge, quite remarkably, had a brother, Bill Trowbridge, who guess what, only became skipper of little ship the Bee at Dunkirk, standing shoulder to shoulder with a certain Fred Reynard who was the ship’s engineer. So if you cast your mind back to the brave effort that Fred Reynard and Bill Trowbridge put in at Dunkirk, rescuing soldiers from the beaches,

no wonder they were so determined with the fighting history they had behind them – One whose brother was killed fighting bravely at Gallipoli, the other who was himself NEARLY killed doing the same thing.

So, by a country mile, I feel very justified in saying - How good is that?!

As a little epilogue to this passage, I’ve got a quote from Michael Wills who as a lad actually knew hero Fred Reynard and of course Bill Trowbridge was Mike’s great uncle!

“I remember Fred so well in his blue overalls. He passed my house on his way to and from the quay and he always acknowledged us scruffy lads playing in the street.

The engine room was very much his territory and one only went there by invitation. Nevertheless, he occasionally proudly showed us round.

He was aware that being engineer gave him some status. He had his tea in the engine room or with my uncle in the wheelhouse, not with the crew in the forepeak cabin.

Best wishes,

Mike

Mike thanks for that little memory - we can now imagine how Fred would have taken great exception to the enemy bombing and strafing his beloved little ship Bee!

It gets better, kind of:

3 Helen Westbrook has won a competition

Helen’s from Newport on the Isle of Wight near Southampton in England. She’s the granddaughter of Fred Reynard whom I’ve just mentioned. And she’s previously sent us Fred’s memoirs of Gallipoli and Dunkirk.

And I’ve got to congratulate Helen because she’s won a Sunday Times Great War story competition for an extract from Fred’s WW1 Gallipoli memoir.

Helen’s magnificent prize was a 6ft tall metal-framed silhouette of a rifle-bearing British Tommy provided by the There But Not There commemorative campaign. There’s a photo of Helen and Tommy in the show notes along with a link to the There But Not There campaign where you can purchase a Tommy figure for your home to remember the fallen and help raise funds for veterans' charities today.

If anyone has listened to the Gallipoli episode they will be only too aware of the number of times Fred narrowly escaped death in the brutal fighting that took place.

Helen’s winning entry read as follows:

“My grandfather Fred Reynard was born in 1895. He served in the army and fought in several campaigns, including Gallipoli. He kept a diary, from which the quotes below show some of the effects the war had on his life. He lost his younger brother Charles and his great friend “Dink” Watson, both killed in action.

“I saw Dink fall wounded, trying to reach a man in no man’s land. No time to think, I found myself running towards my pal. He was still alive and said: ‘Sergeant Freddie.’ Where my strength came from I shall never know, I threw him over my shoulder and started back, a hail of bullets following me.

“Something hit my side and it pained a little; then a bang on the chest as I tumbled with Dink into our shelter. Dink was dead, we could do nothing for him. A bullet had broken my bayonet off short and had driven the steel of the scabbard into my hip, tearing the flesh. Another hit the prayer book I carried in my breast pocket, the steel mirror inside had deflected it and so saved my life. The mirror was one that Dink had given me.

“I was sick of heart, mind and body. I had seen men whom I had grown to love and respect, men I had eaten, joked, fought and knelt in prayer with just wiped from the face of this earth, without a chance to hit back or bid their families goodbye. I buried my head in the dust of the trench and cried.

“Some of the things I saw, perhaps, it is better not written, for it would bring no credit to the human race. Nevertheless, my experience is one that will always live with me.

Fred survived the First World War and in May 1940 was a crew member aboard the civilian vessel Bee, assisting in the evacuation of Dunkirk. He died at home in 1987 at the great age of 92. As I said goodnight to him the night he passed away, he grabbed my hand and said: “Cheerio, I can hear the guns again.”

So Listener that’s the end of Helen’s competition-winning entry and I know how deserving it was, having read the full version of Fred’s memoirs multiple times. WW2 and WWII podcast.

And judging by the feedback I’ve had from listeners, Fred’s Gallipoli memoir ranks very highly on the list of favourites. So if you haven’t yet heard it yet, get yourself over to episode 16 Gallipoli where you will hear the full and truly impressive memoir written by someone who was party to one of the most brutal battles of WWI.

As a postscript to this story about Helen, she later added “I had the great honour to be asked by the Lord Lieutenant of the Isle of Man to read my competition entry in Newport Minster. As you can imagine this was both a scary and very proud moment, Tommy was in attendance too.

But it was only when the Sunday Times contacted Helen about the competition prize that they found out that her grandfather nearly didn’t get to fight in the Great War at all.

It turns out, even before WW1, Fred Reynard had already diced with death:

In 1912, he’d left his home on the Isle of Wight to start a new job

— as stoker on a passenger ship.

That ship was only called the Titanic.

But evidently heavy fog in the waters of the Solent held up the journey from his island home to Southampton and the ill-fated ship left without him.

So Fred Reynard, hero of Gallipoli in the first world war and engineer on board the valliant ship Bee at Dunkirk in WW2, only did those things because he escaped that fateful voyage of the Titanic!

So next time you complain about the weather on a foggy day, just think that sometimes bad weather does sometimes have its advantages.

Go on then, we’ll just have to have another How Good is That award! So that’s two in one episode, wow!

And there’s more Dunkirk stuff …!

4 Harry Downer

There’s a photo of Dunkirk little ship the Bee with its crew in the show notes, looking tough and determined.

We’ve heard the backstories of Fred Reynard, engineer on The Bee and now Bill Trowbridge, skipper. There are three other characters in that photo. And because of the power of the internet someone has just written to me to tell me about two of them.

There’s a shiver just ran up my spine as I’m reading this.

I’ve been emailed by Kevin Downer saying he stumbled across my show notes via a Facebook comment.

“My name is Kevin Downer

The picture of The Bee crew shows Fred Reynard engineer, Captain Bill Trowbridge and Harry Downer first mate and his young son Ernest (Muddy) Downer.

Harry Downer was my Grandfather and Ernest was my Father.

I believe the photo is circa 1935 (before the outbreak of WW2) which would be when my Dad was around 10 years old. Listener I’ve posted the picture Kevin’s referring to in the show notes.

Here are some short stories which will give you an insight into the characters of both my father and my grandfather.

My Dad Ernest served in the Royal Navy during WW2. In 1940 he went to sign on for the war effort and when he went to the desk there was a naval officer and a civilian taking information and filling forms out. When the naval officer asked for Ernest's age and date of birth he gave a false date of birth.

The civilian was a local counsellor and a very close family friend. He looked up and knowing my father’s real age was only 15 said to Ernest, 'Does your Dad know you are here?' Ernest retorted, 'It was my dad who sent me'. He duly signed-up that day at the tender age of 15, but did not go to war for another couple of years - after training at Sea Cadet Corps.

So that’s a little background in tribute to the young lad in the Bee photo. He didn’t serve on the Bee but nevertheless a little bit of the grit that runs through the family showing up there. Kevin goes on to talk about his GF, Harry Downer, the chap who served on the Bee at Dunkirk.

He was a short man of not more than 5ft. 5ins. (1.65m) and I always likened him to comedian Norman Wisdom in looks and build and also being very, very funny and always happy. However he was ruled with a rod of iron by my Grandmother and he would do everything she told him to do. He loved his gardening and won many awards for his vegetables, especially his prize onions, which he would give away freely at the Harvest festival.

Harry was affectionately called Paps by all his grandchildren, but among the older family members he was referred to as 'Scrapper'. This was because the family didn't want the authorities (or anyone else for that matter) knowing who they were referring to when talking among themselves about Harry; this label was due to him going into town on a Friday night for a drink and looking for anyone to have a fight with, which would usually involve a soldier from the local barracks.

As locals knew him only too well and how hard he was, they would even avoid him by crossing the road if he was coming in the opposite direction on a Friday night. It was only a few years ago that I learnt that Harry had served in the army and was shot and seriously wounded in Northern Ireland in 1923. I don't think he was in WW1.

Long after WW2 in around 1966 my GF Harry had a very serious accident aboard the Bee which resulted in him totally losing all four fingers of his right hand.

I vividly remember the nurse coming to dress his hand and my grandfather insisting I stayed in the lounge to see his mangled hand and watch the nurse dress his wounds, stating “He's a Downer so he'll need to harden up some time” I was 5 or 6 at the time!

But I have fond memories of him and as we only lived a couple doors away I was always in and out of his home.

After my Grandmother died, I would take him out to a country pub for a pint which he thoroughly enjoyed. Sadly this was only enjoyed a few times as Harry died just 6 months after his beloved wife, in 1980, of a heart attack.......He was 80.

At no point did he ever speak of his time in the army or of his Dunkirk experience, choosing instead to recall family stories and how to properly conduct one’s life in a polite and proper manner. I do remember him adorning all his medals and proudly attending the Sunday remembrance services each year held in the main square in Newport.

He was buried at the cemetery wearing all his medals which was his wish. I hope this gives you an insight into the man who was my Grandad, Harry Downer.

Although a short man in stature, he was a big man when it came to heart and courage.

Mark – thank you so much for filling us in on that background to your GF. Just brilliant. So we now have the stories to three of those heroes who manned that little ship at Dunkirk – all tough, strong characters.

Fred Reynard, survivor of Gallipoli

Bill Trowbridge whose brother Harry was killed at Gallipoli

And now we’ve just heard the background to Harry Downer, first mate aboard the valiant Bee.

You know I really feel quite privileged knowing all these guys’ stories and how they’ve come together like this. This isn’t stuff you’ll find in the history books!

There’s just one crew member missing, Marc Hocking, aged 18, who was fourth hand. Does anyone listening know HIS story? Please get in touch!

I have to say that I think the relatives of all these men and other little ships that were crewed by civilians at Dunkirk should be mightily proud of them. And I think we’re so lucky that someone made an effort and took some photos of them to pass down to future generations.

5 Interlude

Anyone looking for new history podcasts to listen to might like to check out the one I’ve just found and enjoyed. It’s called Unknown History and it’s now entering its third season, which is all about D-Day, often referred to as the longest day in military history.

They’ve got tales of survival from fighters and bystanders on all sides of the conflict – and the first episode is a true adventure story about a secret landing on the D-Day beaches - - before D-Day.

Unknown History is written and hosted by bestselling historian Giles Milton, whose books have sold almost 2 million copies.

It’s expertly researched, and rivetingly told

and you can find it wherever you listen to podcasts.

Look out especially for the D-Day season - I’ve put a link in the show notes.

That’s Unknown History

Interlude

Fred Bates was one of the first soldiers onto Gold Beach in 1944.

Nathan Portlock-Allan just wrote to me and said “I am a filmmaker and have just started a non-profit, personal project recording some of the last WW2 veterans. I have just finished the edit on the first one with Fred.

I think Nathan has done such an exquisite job with this and I’ll defy anyone not to have a tear in their eye by the end of it. Here’s just a short clip to illustrate what you’ll get.

It’s all very interesting for me because Dad also landed on Gold Beach. Fred was part of 231st Infantry Brigade which in turn was part of 50th Div. As I understand it 231 Brigade was an additional brigade brought in quite late on in proceedings, to bolster up the attack on Gold Beach. So that could be why Fred claimed he’d had no training. Poor lad, no experience, no training, and being shoved off a landing craft on Gold Beach wow!

So – homework for this week: Go to my show notes and take a look at the youtube link. And give it a like and comment if you feel so moved.

Nathan has done several interviews with veterans so you might consider subscribing to his youtube channel so you catch any future releases. I for one cannot wait to see the rest.

If there’s any more news I’ll give you an update.

And while we’re on News:

Thanks to Davy Maclean who responded to my plea in a previous episode for the whereabouts of the defunct North West sound archive. Davy made some suggestions which I’ve followed through and it seems the archive was shared between the Lancashire and Manchester archives. Sadly they aren’t online but from the list they have kindly sent me there are clearly some memoirs that will be worth digging out for future shows. Some are on tape, others on disc, just waiting to be discovered!

Thanks again Davy.

Interlude

You’re listening to the Fighting Through Podcast, Episode 40, Four Brits and a Frenchman – Great Unpublished History - WW2 and WWII

6 Feedback

I want to share some of the recent feedback I’ve had about the show and to give a few shout outs out! Thank you so much to you if you’ve been in touch about the show – whether it be likes or comments on Twitter of Facebook, emails or other messages. In particular thank you if you’ve subscribed to the show – it’s totally free to subscribe in your listening app and when you do so your app will automatically download the show and give you a notification that it’s been released.

So today I’m making a plea for you to subscribe as it will help me in the podcast rankings which in turn will help others to discover your favourite WWII history podcast – and who knows what precious memoirs that might help uncover at some point in the future?

I now hereby declare Mr Jonathan Martin of Britain to be listener of the month for his kind sponsorship on Patreon. If you’d like to send me the price of a cup of coffee or more to help cover the costs of this show, look for the donate links on the FTP home page – and you can now very easily make contributions by PayPal – either one off for an episode you’ve particularly enjoyed, of a monthly donation if you prefer. Thanks again to Jonathan.

Here’s a few shout outs for various people who’ve been in touch:

Poppy on youtube

What a story! I’m a great fan of the podcast from ep.1 and all that followed. Still working on the maps and routes and when these personal accounts are told and listened to it becomes a harrowing experience. Unimaginable. Usually it is told as a 'grand scheme' and 'largest operation' which of course it was. And usually from an American perspective.

But these young fellows are from all over the world treading in sand working their way up to a pillbox while under fire and with their friend wounded and dying around them it’s a true account of that horrible war.

I hope all rest in peace and with the greatest respect to all the soldiers I say thank you Sirs for the greatest fight against the Nazi war machine. And thank you Paul for telling this story. Let it live on forever and may we never, never forget.

Jewels Renee Facebook

I just discovered your podcast last week. I haul horses and drive at least 12 hours a day, two to four times a week. My grandpa Robert Reavis was a test pilot. I was so young when I heard his stories a million times and I can only recall a few.

I love World War II history and World War 2 airplanes! I have made it to episode 35 and I only started listening last week.

I’ve been in touch with Jewels and she’s sent me a stack of material on her Grandad, so I’m hoping to use it in a future show, including one or two quite startling revelations about him, so keep yer ears peeled listener!

Dave Hambly from Engkand has just hinted at a few possible stories from his family.

I work long hours on the road and without you knowing it, you have become a good friend keeping me company in the cab. I love the history you are unveiling and the way you deliver it.

The interest sparked by the podcast has made me realise firstly how involved the west country (where I live) was in the war. Many of the camps, based and airfields you’ve mentioned I still visit today on a professional basis. You’ve also reminded me of the involvement of certain family members and their heroic stories.

My most impressive tale is one from my sister in laws uncle who was a Japanese prisoner of war and how he survived and gained a Japanese generals samurai sword. And the unlikely love story which unfolded after his release.

So hopefully David you’re going to give us a bit more detail on that fascinating tit bit of history. We’ll all be watching this space. That mention of the samurai sword reminds me of a Nazi flag my Dad brought back from Germany … Enormous thing. Blood red, Swastica, Eagle, immaculate I used to use it as a bed spread in the seventies. But then Dad needed the money and we sold it, in the 70’s for around £70. A lot of money in those days.

One treasured item in Dad’s surviving souvenirs is a miniature Nazi dagger with a slim stainless steel blade, an ivory handle and silk cord. It’s in a sheath and has a small swastika at the hilt. I used to use it as a letter opener for a while till I realised it warranted a little more TLC, so now it sits in a special display cabinet along with a number of other treasured possessions such as a copy of the motivational speech Monty handed out to all the troops before D-Day. I digress.

Thanks to the following for their comments on the show:

Brian Gould - Facebook

Gerard Paynter BRISBANE Australia - Facebook

Cindy McQuaig Nessing from Atlanta Georgia. Facebook

in iTunes by notbychance from UK

Alan McManus

All comments get posted on the feedback page at Fighting Through Podcast .co.uk

Finally - Feedback of the month:

I’ve recently been listening to Max Hastings being interviewed by Dad Snow on the History Hit podcast about the Vietnam war. I’m not sure what was most entertaining, Max’s valiant attempts at an American accent or the excellent history lesson. But it’s inspired me to do my best with the following listener’s comments because he’s literally written exactly the way I guess he speaks. Here goes:

Andy Charlie Nanos had been in touch on Facebook from a town called Koo Wee Rup in Victoria Australia.

Gday mate all the way from Australia. I’ve just started listening to ya podcast while I’m workin on the farm. Absolutely fantastic mate - great work you’re doing and the Gallipoli diary - crikey mate so well detailed. Fred Reynard was a great bloke especially for his work at Dunkirk. The first hand accounts from the veterans themselves is very special.

That’ll do – back to English English now!

I’m right into my military history. And I do WW1/WW2 re-enactment. I’ve been to France and Belgium in uniform for anniversaries but we live and train and eat as soldiers when we do it, and for ww2 I’m part of a 25pdr crew.

Our gun still fires and saw action in Syria. We train a lot for that – we’re like living history. Anyway mate keep up the great work and looking forward to hearing more and more - cheers.

Andy, thanks so much for that feedback – just brilliant how much you’re into your re-enactment hobby and I wonder if you’ve had any of that famous Bully Beef that several of our veterans have talked about!

Anyway Andy came back with some more info about his Re-enactment group.

They’re ALHF Australasian Living History Federation ... and NMRG National Military Re-enactment Group. Andy and his mates are going to be part of a major state air show soon, so here’s an official shout out for you guys. I’ve posted some photos of Andy in the show notes at a variety of events. There’s one great one taken with an old Brownie box camera, so it comes out sort of imperfect and of course black and white, so it’s a real authentic looking photo of the group as they might have looked so many years ago. Andy you really should get that pic colourised by an expert.

Cheers cobber! Bye for now.

INTERLUDE

You’re listening to the Fighting Through Podcast - Episode 40 - Four Brits and a Frenchman at Dunkirk, Great Unpublished History!

INTERLUDE

Right here we go:

Four Brits and a Frenchman at Dunkirk

Maurice Bourel

I’m about to tell you the story of a Frenchman who was involved in the Dunkirk episode of WW2, who had the most remarkable escape from the beaches.

All the places mentioned are pretty much in the vicinity of Dunkirk, and I’ll just remind you that Britain declared war on Germany on 3 September 1939 and Germany invaded Holland on 10 May 1940.

Frenchman, Benjamin Bourel, has just written to me

Dear Paul,

I am French and I live near Lille in the north of France, where my whole family is from.

My grandfather died in 1994 when I was 14 years old. So I knew him very well but I regret not listening to him more when I was younger. Now, after many years, I’m trying to trace his story in as much detail as I can. And connections like yours are extraordinary for me.

My grandfather Maurice Bourel was evacuated from Dunkirk aboard the Lady of Mann after being wounded near Dunkirk. He was first treated at Zuydcoote (Zweetcote) Hospital and then boarded the Lady of Man on May 31st.

Thank you, Benjamin.

I was fascinated by Benjamin’s email because when I re-read it and checked what he’d said I realised that the date his GF was evacuated from Dunkirk on the Lady of Mann was the same date as Dad, 31 May. And as there was only the one sailing that day, it meant that Maurice Bourel was on the ship at the same time as Dad!

They might have been standing next to each other, both eyeing up the same Carley float in case the ship was sunk, both watching the same scenes unfold at the same time as ship’s Captain Tom Woods and company commander Major Petch were – we’ve got podcast episodes on both their memoirs. So they saw the enemy bombs falling towards the ship, the soldiers being knocked down like dominoes on the beach, the burning oil tanks.

They’d have seen the holes in the wooden flooring of the Mole where an unexploded bomb had gone through, the soldiers with full kit daring to jump across in haste.

You know what I’m going to say next don’t you and I’m almost reluctant to say it because I’ve said it twice already – but hey it’s happy new year 2019 so what the heck – HOW GOOD IS THAT?!

I sent Benjamin a quote from Dad’s book, FTFDTH.

"About 1.30 pm we got a birth at the pier [the East Mole] and began embarking French casualties from the French hospital. We took 1500 casualties on board of which 300 were stretcher cases, also 500 other French troops and 1000 British."

Benjamin confirmed:

“My grandfather was one of those wounded.

We know his story quite well because my grandmother is still alive – she’s 97 years old, so she’s talked to us about my Grandad’s experience and has started to write a few lines about him.

“My husband left home [to join his army comrades] on the 3rd September 1939 after a holiday in the River Aisne area. He was away until the attack on Belgium, coming back from Belgium on 20 May 1940.

He came back to Fromelles to my home so we could get ready to evacuate within three days.

We went back to Merville to his parents’ home, where his father told him to stay, for in any case, this was the end.

He wouldn’t accept this and went to join the soldiers who had been encamped for a few days at the Nieppe woods before leaving to defend the attack on Dunkirk.

After going into battle he was wounded in the foot at La Panne, 28 May 1940

With a broken foot, he was taken to the hospital at Zuydcoote, [not far from Dunkirk].

This is Benjamin’s broader account of his GF’s actions:

Maurice Bourel was a volunteer, and at the beginning of the war he moved to the 39th Combat Tank Battalion where he started fighting in the Namur region (Belgium). During the debacle of the French army, he retreated towards Dunkirk to lend a hand in the defence of the city.

Then he was wounded in the foot after a strafing by German planes at La Panne, just east of Dunkirk (May 28). He was hospitalized at Zuydcoote in the military hospital in the Sanatorium.

But the hospital was bombed, so, with his foot in plaster, he managed to flee on a bicycle with no tyres, with the help of a comrade who also had a broken finger! They joined a Red Cross ambulance convoy who transferred the wounded to the ships for evacuation. I do not know exactly how he got onto the Lady of Mann, but my Grandma is certain this was the ship that took him to England.

He landed at Folkestone and probably took the train to Southampton.

He then finished his convalescence in England (firstly Berkhamsted then Southport), before joining General de Gaulle in London.

He was then sent to Africa where he fought with General Leclerc (Fezzan Campaign, Tripolitania campaign, and then the Tunisia campaign). He then joined the British 2nd Armoured Division, in England, and landed in Normandy in August 1944.

He then did all the campaign in France (Battle of Normandy, Liberation of Paris, Liberation of Strasbourg and capture of Berchtesgaden) until the end of the war.

Unfortunately my grandfather did not leave any writing. But my grandmother remembers very well that he told her about the Lady of Mann ...a name that is not forgotten! My grandfather left a map which he drew in 1945, after he got back from the war. On this map, we can see that he left Dunkirk on May 31, 1940.

So there we have it:

My Dad, 6 Battalion Green Howards, his company commander Major Petch OBE, Captain Tom Woods OBE of the Lady of Mann ferry ship and Maurice Bourel together …

THREE Brits and a Frenchman all, for a moment at least, safely aboard the Lady of Mann, bound for England – and as my Dad put it: “The other side of that water was England. Oh, that lovely sea, with England just on the other side – how simple!

And for anyone who hasn’t had a chance to listen to the Captain Tom Woods Dunkirk episode, I’ll just remind you that Sarah once told us that “Tom had 3 sons of his own in their 20s at the time and the reason he insisted on going back for several repeat rescues was because, he said, every one of the men in the water was somebody's son.

This is what Dad said in his memoir about leaving Dunkirk, after all the drama of the previous few weeks:

“As the ship was filling up, a Padre came and stood on a ladder, called for silence and prayed for our deliverance to England. At last, packed like sardines, the ship started to tremble and, so very slowly, we pulled away from the Mole – it was 1800hrs, 31 May 1940."

I’ve posted Maurice’s map in the show notes and it’s quite detailed. It shows the routes of the ships Maurice sailed on to Africa and back, possibly on the same ship as Dad such as troopship HMT Otranto – though not at the same time on these occasions.

Maurice sailed out in March 41 and returned 1 June 44 just in time for the Normandy campaign. And he’s marked so many places on the map of Britain that my Dad also travelled through or past – Folkstone Southampton London Dover Glasgow – what an adventure it must have been for him at that time. And he even fought in Tunisia, as Dad did, though I believe it was different battles.

Sarah Parry was very interested in Benjamin’s family history, because it was her great grandfather who’d captained the ship that brought Benjamin’s grandfather back. She said

“Wow, thank you so much for sending me this Paul. It brought a little tear to my eye ;) It’s wonderful to think that, through your podcast, so many connections are being made and people are able to piece together so many individual stories to gain a greater insight into their ancestors’ experiences at Dunkirk.

Sarah wrote the following to Benjamin:

Dear Benjamin,

Thank you so much for the wonderful photographs of your grandfather. What an eventful time he had and how lucky he was to come through in one piece. It is quite something to think that even after the traumatic events of Dunkirk your grandfather went on to experience and achieve so much more in Europe and Africa.

I find these stories fascinating. How amazing that we have managed to make contact and put together some of the pieces of this great puzzle.

We are complete strangers but years ago the paths of our ancestors crossed for a brief moment and influenced future events.

Sarah

Photos

I’m posting the photos that Benjamin sent in the shownotes.

One shows Maurice in August 1940 at the Southport hospital where he convalesced together with two Australian nurses who looked after him, one of whom was called Francis Croack? Walsh? As Benjamin said, it would be fabulous to identify other people in the photo.

Listener, if you’ve got connections with Southport and know anyone who has Australian-connected family who were nurses in the hospital back in 1940, please get in touch. Are you a local Southport historian who might have access to some of the records?

How good would it be for someone connected with those nurses to come forward and share some memories of that dramatic period?

There’s second photo, taken in London, in front the Carlton Gardens, the headquarters of General de Gaulle in 1941 (Apparently Maurice was part of De Gaulle's guard). And there is actually a statue of GDG in the Carlton Gardens opposite the building that he set-up as the Free French Forces Headquarters, during WWII.

There’s another photo from Libya in 1943

And one more from 1982, when Maurice received the French "Légion d'Honneur" medal.

Listener if you can free your hands or your mind from whatever you’re doing right now, perhaps you’ll join me in a hearty round of applause for Maurice’s valiant services and especially in support of that Legion D’honneur he was awarded.

Just excellent.

You know It’s funny but I sometimes feel we Brits think we won the war on our own and we forget or are just ignorant of the roles played by so many allies – but in fact if you google the details of which countries did play their part in the fighting, it’s massive – around about fifty nations were involved, including America, Soviet Union and of course France! WW2 WWII

And how’s this for another coincidence?

Sarah Parry informed me that almost around the same time that Maurice was in the Southport Hospital, her grandfather, Robert, was actually in a jeweller’s shop on the main street.

Sarah says:

“It’s strange that Maurice convalesced in Southport. My grandfather Robert, Tom’s son, bought my grandmother’s engagement ring in Southport that summer. I still have the receipt and the diamonds are now in my own ring!

Robert and his family, including my dad, moved to Southport from the IOM to live after the war. I was born in a Southport hospital a stone’s throw away from the military hospital - 26 years later!

And listener when I’ve previously mentioned this to my Mum she said she knew exactly where this ring was bought because she knew the area and it was Neville Street – shown on the receipt from W Wright jewellers, 18 Neville Street. And I can confirm that shop is still there – but it’s now a newsagents called Mike’s News! Right I’ll take my trainspotter’s hat off now and get on with it.

Benjamin – thank you so much for getting in touch with your GF’s story. It’s been a revelation and soooo good to make the connections with the other characters in this extraordinary tapestry of WW2!

Please give our very best wishes and love, from around the world, to your fantastic grandmother and thank her for the part she played in preserving this absolutely precious bit of history.

There’s more – it’s about a British soldier who died fighting at Dunkirk – Fred Gardiner – the fourth Brit - coming up next … but take a breather …

INTERLUDE

You’re listening to the Fighting Through Podcast, Episode 40, Four Brits and a Frenchman – Great Unpublished History, WW2 and WWII

Lt Gen A Brooke once said of his evacuation from Dunkirk:

‘I am not very partial to being bombed whilst on land, but I have no wish ever to be bombed again whilst at sea. I have the greatest admiration for all sailors who so frequently were subjected to this form of torture during the war’

That was brought to our attention by Andrew Newson on his Twitter page @Dunkirk_1940 - I’m putting a link in the shownotes. Andrew is very active in social media on the subject of Dunkirk.

You can also check out Andrew’s France and Flanders Campaign Facebook page – He has a great photo gallery of Dunkirk pictures – possibly the best you’ll find really because there’s always comments and observations from page followers which increases interest in the photos. Again, I’m putting a link in the shownotes.

8 Dorothy

I know 40% of you are now jumping up and down in your car seats wondering who the fourth man is – who is the mysterious Brit at Dunkirk that we’ve not heard about yet?

You’re now going to hear of the brave role played by one soldier killed in action whilst performing a rear guard action at Dunkirk.

If

You go to YouTube and search on The East Mole, or if you go to the videos page at FTP.co.uk, you’ll find me presenting my own videos of the Mole and the beach at Bray Dunes near Dunkirk, and I hope it helps you to picture the scenes back in 1940 when you listen to this show.

Dot McQuillen did just this and emailed me a few months ago.

Hi Paul, I came across your podcast on YouTube. I hadn’t even heard of Bray Dunes but recently I found out that my uncle, Frederick Gardiner was killed on the road at Les Moeres just outside Bray Dunes when a group of Junkers bombed their company, on, 28 May 1940.

They were holding a bridgehead on the road just outside Bray Dunes to keep the Germans off while the British Expeditionary Force BEF escaped to the beach. He was part of a small Company - C – of the 8th Battalion Kings Own Regiment, commanded by Captain J H Everett. 40 men were killed in the air raid and the wounded couldn’t be recovered because of the fighting.

They were buried in a mass grave at Bray Dunes and then after the war they were exhumed and 17 of them were buried in Adinkerke cemetery. My uncle was one of the 17.

Dorothy McQuillen, UK

I’ve been researching my family tree some ten years and I know Frederick Gardiner was my mum’s youngest brother.

And she mentioned to me that he died at Dunkirk protecting a Belgium woman and child, though I’ve not been able to find out any more on that front.

Born in 1911 in a two up two down, he was a handsome easy going man in no rush to marry with a good sense of humour but always a bit of a risk taker. Nothing like his two older brothers whom I both knew, and who were very quiet sober men!

I’ve dug out a map of the area and put it in the show notes and it illustrates how the junction, and bridge, at Les Moeres is just a stone’s throw from Bray Dunes.

So it’s pretty obvious my Dad and his comrades would have gone by that junction as they made their way to Bray Dunes. And Maurice Bourrel is likely to have gone that way too. I believe quite a lot of that land is marshy and could even have been flooded so soldiers would have tended to stick to the roads. Having said that Dad did say in his memoirs that they avoided the roads when they could.

Here’s a short passage from Dad’s memoir, FTFDTH, which offers a very clear picture of the absolute havoc that reigned at this point. Dad had just spent several weeks fighting the Germans, and his battalion had scored several wins in hard combat, so they had proved their mettle:

“Our officers had to guide us out of this nightmarish debacle and leave the stubborn defence of the perimeter to the more experienced and older soldiers who, had they been in possession of sufficient weapons, would not have let the enemy pass. With the weaponry they had, the rear guard at Dunkirk did a tremendous job of containing the enemy whilst the bulk of the BEF escaped to fight another day.

Morale was good after our brush with the enemy at Gravelines and we felt confident that we could put up a sound defence - good north-country lads were not going to be disposed of so easily, even though the enemy had far superior fire power, but we did lose some good boys at this time.

After all is said and done, only three weeks ago most of us had not even fired a rifle, and now here we were, acting as last line of defence in our sector. After two days of beating off attempted infiltrations by the enemy infantry and killing many of them, the order came (during the evening of 29 May) for us to retire further towards the coast at Dunkirk – a distance of about ten miles.

The Regular Army battalion of the Welsh guards was taking over our sector and we had to hand over all weapons, except for our rifles. The Guards, unlike the Territorials, were fully trained soldiers; they had undergone intensive training and all were a year or two older than us Territorial Army men. They had their splendid traditions to uphold and would give any aggressive intent by the enemy short shrift – until they became exhausted or ran short of ammunition.

The evacuation beaches covered a length of coastline running from La Panne to Dunkirk. The sector we were heading for was in between at a place called Bray-Dunes, which was about central and must have derived its name from the sand dunes which ran off the beach. Our path lay across open countryside and this kept us away from the roads which were still crowded with the hapless refugees who were being forced to the side by an endless convoy of all kinds of military vehicles, pushing their way forward in order to get as close as possible to the beaches.

I thought our officers were brilliant in guiding us through that nightmarish countryside. We looked a very sorry sight, covered in dirt and grime, with hunger gnawing at our bellies – I now weighed only ten stones, having lost seven pounds from the time I left England only eight weeks ago.

Difficult as it was, ploughing across farmland with the mud coming above our boots and still being strafed by machine guns from the planes, we must have made better time than those using the roads, because a few miles from the beaches a massive graveyard started.

Many thousands of vehicles had been driven as far as they could get towards Dunkirk, then made useless and abandoned or set on fire. It really is impossible for me to describe the havoc which had been created. Both ways, as far as we could see, the vehicles had been set ablaze, as were petrol and ammunition dumps spreading smoke and flames over a wide area – but it would deny the enemy the use of it. The cost must have been tremendous.

It was some miles to Bray-Dunes. In the distance a huge column of thick black smoke reached for the sky – the oil tanks at Dunkirk were ablaze. I will never forget the sad necessity of so much destruction or the sight of dead soldiers and civilians lying all over the place. Nobody had time to bury them and our medics were already doing more than could really be expected of them, taking care of the wounded.

Then there were the cattle – the poor helpless animals running madly about, scared out of their wits, the dead ones lying on their backs, legs in the air and bloated like balloons. And there were packs of scavenging dogs, almost wild, driven mad by the effects of the bombing. There was no panic; at least I did not see any sign of it. The army just had to make haste to the beaches and we had to try and keep with our own unit. If anybody became separated from his company, it would not have been a very pleasant experience, but as time passed this is what happened to some of the lads.

In the background we could hear the cacophony of war, where the British Army and the best of the French soldiers were giving their all in a desperate bid to hold the enemy back so that as many of the army as possible could reach the evacuation beaches and get away before the inevitable happened.

Many of the rear guards would be overrun by an invincible force, to be taken prisoner to face a most uncertain period of time at the mercy of the enemy, not knowing how long it would be before they saw their loved ones again. It was just as well that the folk at home could not possibly have any idea what their men were enduring or they would most certainly have thought that the war was already lost.

So the actions and sacrifice of Dot’s Uncle and his comrades in defending the territory against the advancing enemy, could have directly helped Frenchman Maurice Bourrel, my father and his Major Petch amongst thousands of others, to escape to safety. I think Dad described the scene really well and was clearly subjected to the same bombing and strafing that Fred Gardiner had to endure whilst he and his mates bravely guarded that junction, at the cost of their lives. And the very presence of Fred possibly diverted those enemy planes enough that they were short of ammo to go and bomb the waiting Lady of Mann at the Dunkirk mole, who knows?

I'm feeling quite emotional about this, I have to say, and the coincidences which keep coming up in my researches for the podcast continue to be breath-taking, they really do.

I wrote back to Dot to see what else she’d learnt about her uncle and she sent me some papers she’d collected. She’s been trying to piece together exactly what happened to her Uncle because part of his regiment got back to Dunkirk leaving Fred still guarding the road junction some seven or eight miles away.

Firstly an email from the curator of the Kings Own Regimental Museum.

“I have to say that there is little to go on to actually establish what the 8th Battalion, or indeed any battalion of the King's Own, was doing in the brief campaign in France and Belgium in 1940. There was clearly a great deal of confusion in the fall back to the beaches and during the evacuation I would guess that war diaries, and any other paperwork, was generally lost, no doubt burnt as the orders were given to withdrawn.

The regimental history makes reference to Captain J H Everett holding a bridgehead at Moeres, which is near Bray-Dunes and just to the west of Adinkerke, where the cemetery is. Everett was holding a bridgehead, on 28th May, and I assume they were holding a strong point which would allow our soldiers to access the Dunkirk perimeter and hopefully escape.

A large flight of Junker aircraft attacked the position and killed or wounded 40 soldiers of 'C' Company of the 8th Battalion. A comment is made about the difficulty in dealing with the wounded as there was not transport available to move them anywhere. "17 soldiers were buried in a common grave" and from this my conclusion is that the 17 soldiers of the 8th Battalion who are buried in Adinkerke Cemetery are these men.

I would be pretty sure that Private Gardiner was one of these 17 killed by the large flight of Junkers bombers. This was not uncommon in the campaign, as it was air power which caused major problems for both the British and French armies and also the civilians who were fleeing the German advance.

Dot has been trying valiantly to work out the course of events on that day, but isn’t really any clearer. She’s found out that Captain Everett was mentioned in despatches for the work he did holding the bridgehead.

But Dot hasn’t managed to track down the war diaries for C Company and thinks they may have burnt them in case of capture. C Company did get separated from the rest of their battalion, who made it to Dunkirk. Again it’s not clear how this came about but I guess they were under orders to remain at the bridge whilst the rest retreated.

There is some rather unsavoury history reported by their CO who did find his way down to the beach. It goes something like this:

Dot recently said to me:

“I wish I could find out when the mass grave was dug up at the crossroads and the men reburied in Adinkerke though I expect it was done after the German occupation. I would also love to get my hands on the report for the Military Intelligence Division for Captain John Everett or even locate some of his family”. Another thing Dot has found was an account of the Royal Engineers for May 1940. Their units were responsible for blowing the bridges to stop the advancing Germans. Their BCHQ visited the bridge at Les Moeres at 8.00 am on the morning of the 28th - the day of the bombing.

Listener I’ve been reading this account and it looks like the order to blow up the Moeres bridge was rescinded. But clearly a bridge over water means it was necessary in order to travel around the area so it’s become clear to me that at this point in dad’s journey he would have been using the roads so probably did go over Fred’s bridge.

I noticed that the Royal Engineers in question were part of the 23rd Northumbrian Division which at that point in the war was Dad’s division – so maybe someone knew enough about what was going on to ensure those bridges were kept open at least for the time being to allow allied troops to cross – namely the French and British!

Dot has been doing a lot of research on this whole event and believes that one of the so-called Moeres 17, a well-respected Rev Captain Moss, turned up in a hospital in England later in 1940. So whether there is now another name missing to go with the 17 bodies isn’t clear but I’m putting a link to the known names in the show notes.

If you have any more information or access to the war diaries that might shed any light on the so-called Adinkerke 17, please get in in touch. How did they get separated from the rest of their unit? Was Fred Gardiner really involved in trying to protect a Belgian woman? We’ll probably never know.

If you happen to go to Adinkirke cemetery, do pay your respects to the graves and spend a few moments imagining what these brave lads went through to help secure the lives of other soldiers.

Thank you C Company 8th Battalion Kings Own Regiment, Captain J H Everett, the 40 men who lost their lives at the bridge at Moeres, particularly the 17, including Fred Gardiner, who are buried at Adinkerke, in Belgium.

TRANSITION WW2 WWII podcast

That’s the end of Fred Gardiner’s adventures. Listener, if you can shed any more light on this fateful day, pleased do get in touch.

I just want to round off the episode by reflecting on what we’ve learnt. We’ve heard about Bee engineer Fred Reynard’s various comrades and predecessors Harry Downer, Harry Trowbridge, Albert Sanger and Bill Trowbridge –

and how their backgrounds all overlapped to an extraordinary degree – one which led to such a tough, determined crew on the Dunkirk little ship, The Bee, that performed so heroically in rescuing hundreds of soldiers from the sea.

And then at the same time elsewhere behind the sand dunes, other events took place which led to the death of Fred Gardiner and 40 members of the Kings Own Regiment. But his sacrifice wasn’t totally in vain because we know the junction he was guarding was a key route down to the beaches and there’s a good chance that the presence of him and his comrades helped to ward off the enemy approach to the beaches and the mole where of course Captain Tom Woods and the Lady of Mann were waiting to rescue many thousands of British and French troops, including the wounded Maurice Bourrel and his comrade.

Fred and the 8th Kings Own assisted the escape of my Dad and his comrades along with Major Petch and also of course two other pals of Dad’s whose names I don’t know but the photo of them is in the show notes.

This has all been quite a saga hasn’t it? I must say thank you very much to Dorothy McQuillen and Benjamin Bourrel (Sarah Parry, Michael Wills et al) for taking the trouble to send in their memories. This episode could not have been done without them.

I hope you’ve enjoyed the show, thank you for your support and thanks for making the time to listen to me. Do hear me again soon.

Next episode

Episode 41 is going to be the final unheard interview with the late veteran Wilf Shaw – Oh boy – if you haven’t heard Wilf’s earlier interviews you’re in for a treat – so get bingeing now and you’ll be ready for the final instalment. And don’t forget to subscribe free to the show so you get an automatic reminder. And we’re going to hear a few interesting observations about Wilf from Listener Danny Fontenot who wrote in.

One final request from me – I’d be very grateful if you could spare two minutes to answer a few questions on my listener survey. Just go to my home page at www.Fightingthroughpodcast.co.uk and you’ll see a clear link to it.

And many thanks if you’re one of the many who’ve already answered it. In the not too distant future I’ll be sharing some of the interesting results and comments I’ve had.

PS

I’m going to close shortly with my usual outro music, In Victory. Ever fit, I think, for the occasion of remembering all the brave people mentioned in this episode. Thank you for your service. You’ll never be forgotten.

Not forgetting my Mum Anne Cheall either, here’s the promised tribute to her, with some of her most poignant memories, so fittingly, of Dunkirk 1940. She gave us some great entertainment and I’m so, so pleased I recorded her when I did

So if you want to catch up on what my Mum said about her war years, what she cooked, what she did in the bomb factory, what she did for entertainment and holidays and so many other facets of wartime existence for a civilian, check out my Women at War series on the Fighting Through podcast, ww2.

So thank you Mum. Love you so much.

WW2 WWII podcast

Featured Episodes

If you're going to binge, best start at No 1, Dunkirk, the most popular episode of all. Welcome! Paul.

PS. Just swipe left to browse if you're on mobile.