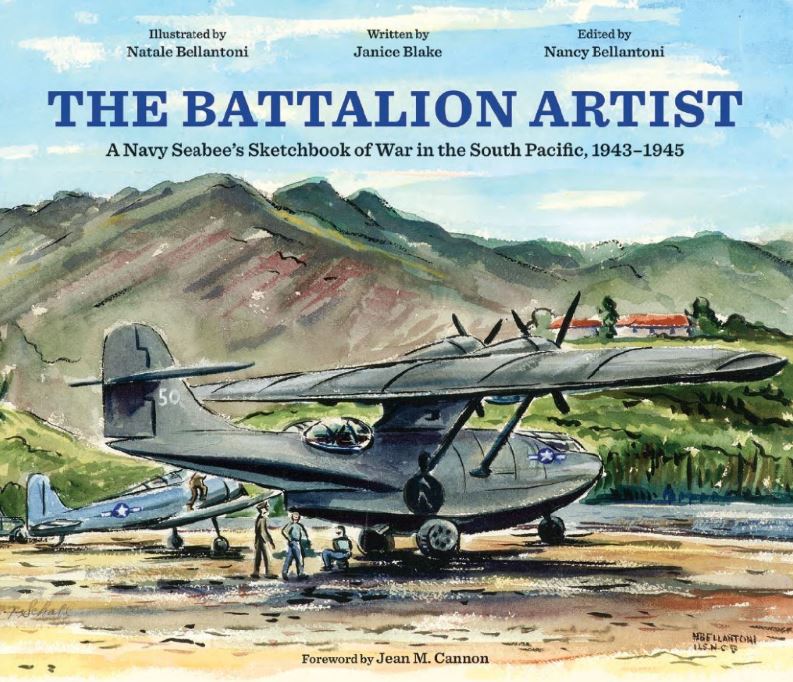

71 The Battalion Artist, Seabees in the Pacific War

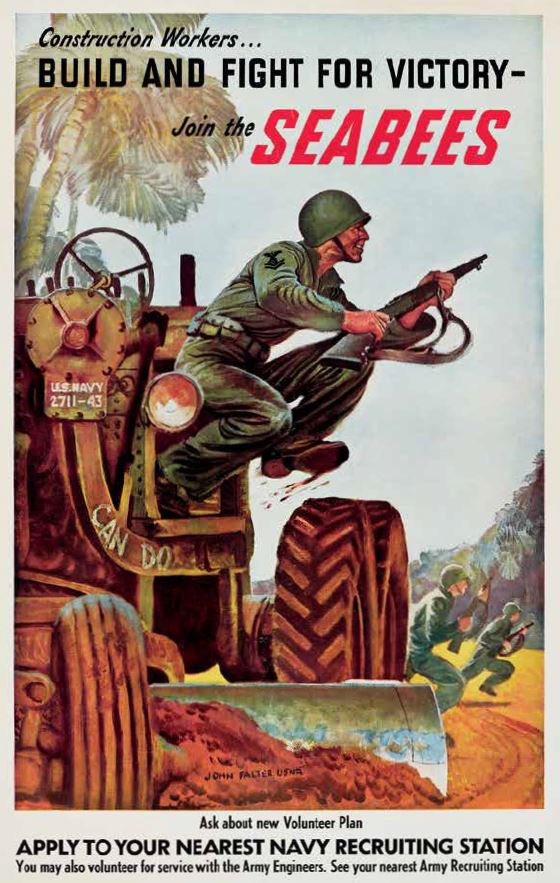

Construction Battalion against Japan WW2

A Navy Seabee’s Sketchbook of War in the South Pacific

The second world war adventures of Nat Bellantoni and his naval comrades in the famous Seabees.

Plus a memoir from Seabee John Serra.

Full show notes at:

https://www.fightingthroughpodcast.co.uk/71_The_Battalion_Artist_Seabees_in_the_Pacific_War

Nat's entire collection of artwork, papers, and memorabilia from World War II, resides at the Hoover Institution Library and Archives at Stanford University. Search for digital collections or use the links in the show notes.

https://digitalcollections.hoover.org/search/bellantoni

https://histories.hoover.org/battalion-artist/

Irene Bellantoni died in 2016 aged 95. Her obituary is here.

https://www.legacy.com/us/obituaries/bostonglobe/name/irene-bellantoni-obituary?pid=183211729

John Serra was a Seabee with the US Navy and served in Alaska, Saipan and in the invasion of Okinawa. He recorded his service and it is on the Library of Congress website Veterans History Project:

http://memory.loc.gov/diglib/vhp/bib/loc.natlib.afc2001001.10960

Feedback/reviews - Apple - https://itunes.apple.com/gb/podcast/ww2-fighting-through-from-dunkirk-to-hamburg-war-diary/id624581457?mt=2

Follow me on Twitter - https://twitter.com/PaulCheall

Follow me on Facebook - https://www.facebook.com/FightingThroughPodcast

YouTube channel - Loads of my own videos - Dunkirk Mole, Gold Beach, much more. https://www.youtube.com/user/paulcheall/videos

Interested in Bill Cheall's book? Link here for more information.

Fighting Through from Dunkirk to Hamburg, hardback, paperback and Kindle etc.

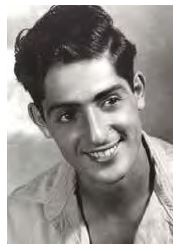

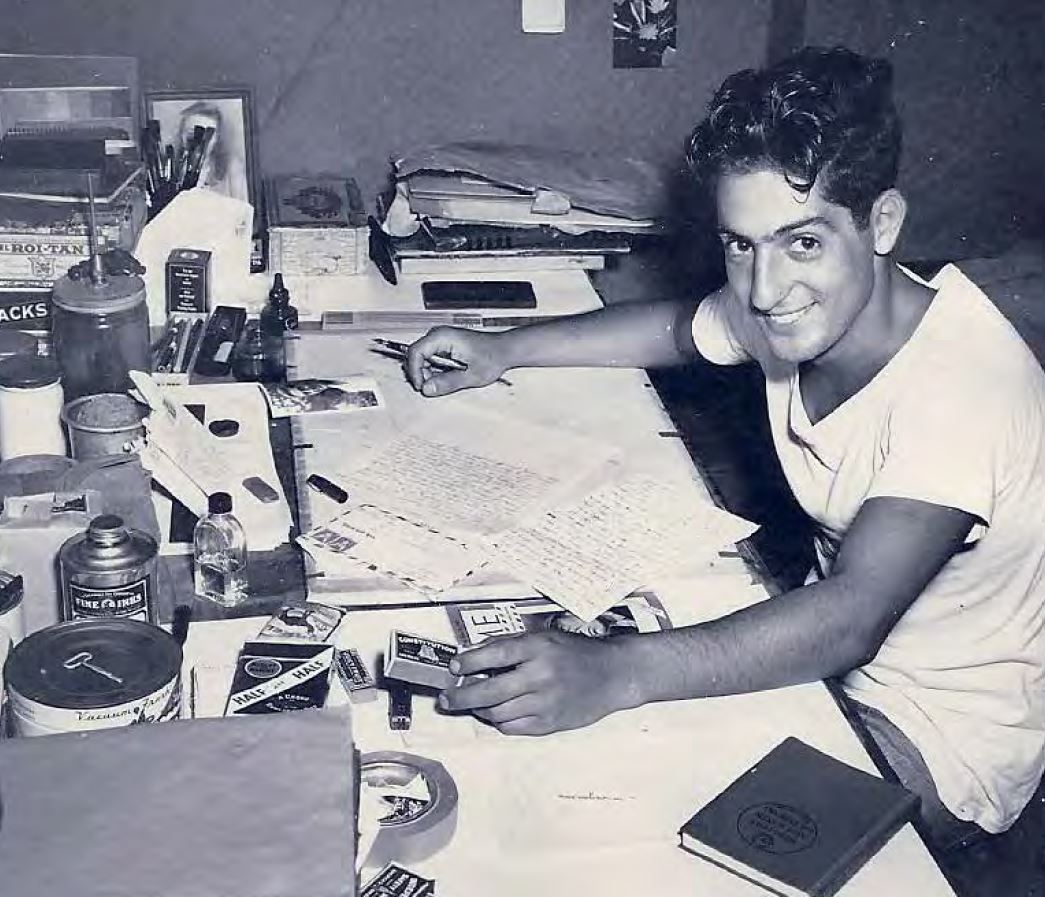

Nat Bellantoni

Young Nat and sweetheart Irene

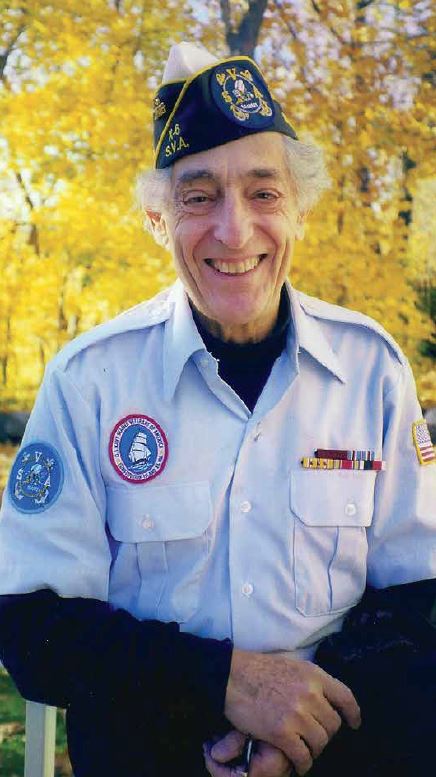

Nat Snr

John Serra 79th Construction Battn, WW2

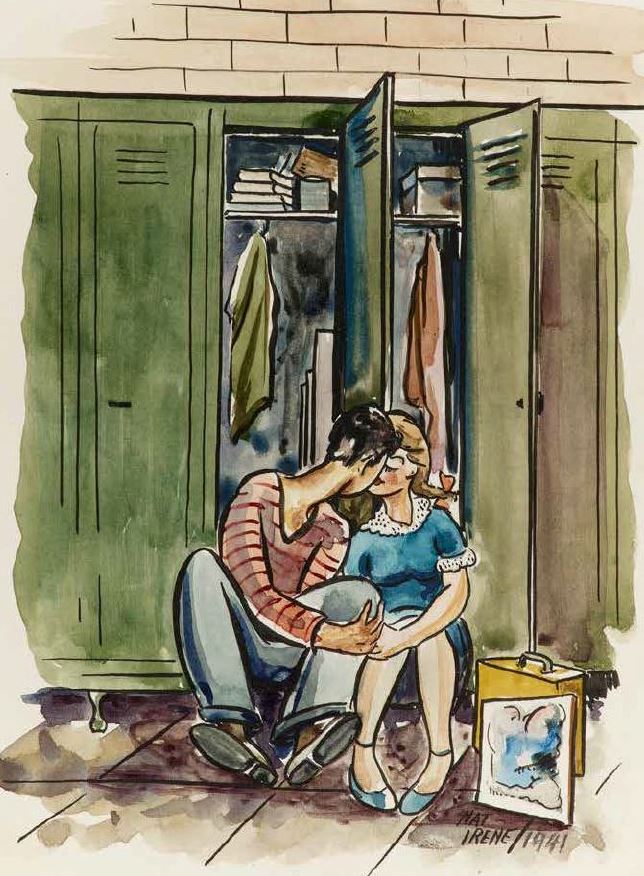

Nat and Irene cartoon

Underway for the Pacific

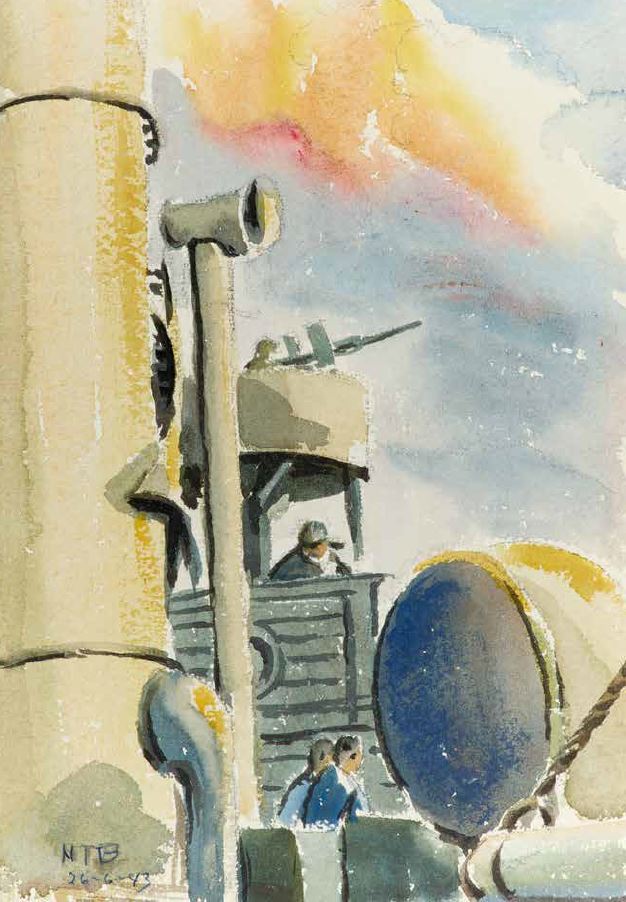

Gun Watch MS Day Star

Scanning the horizon MS Day Star

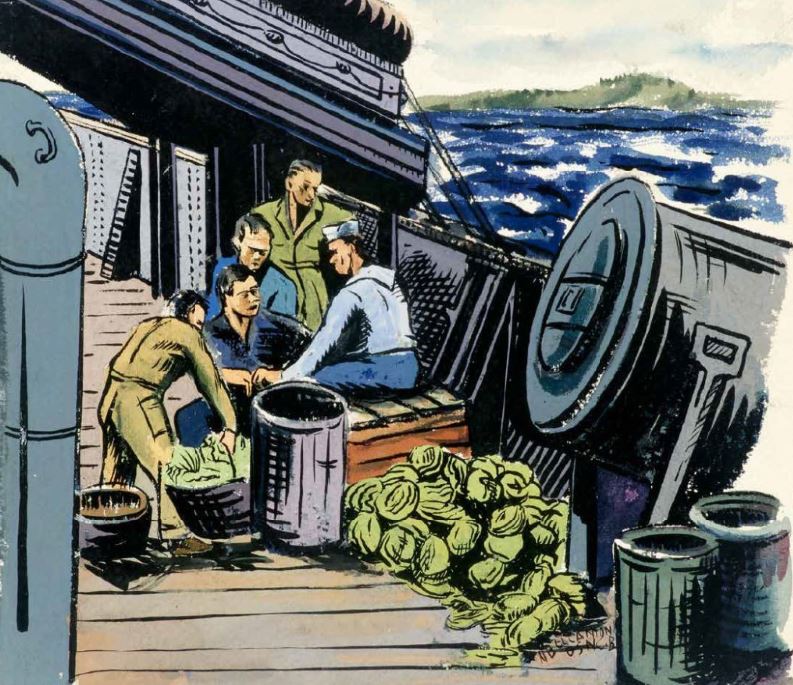

Kitchen Patrol

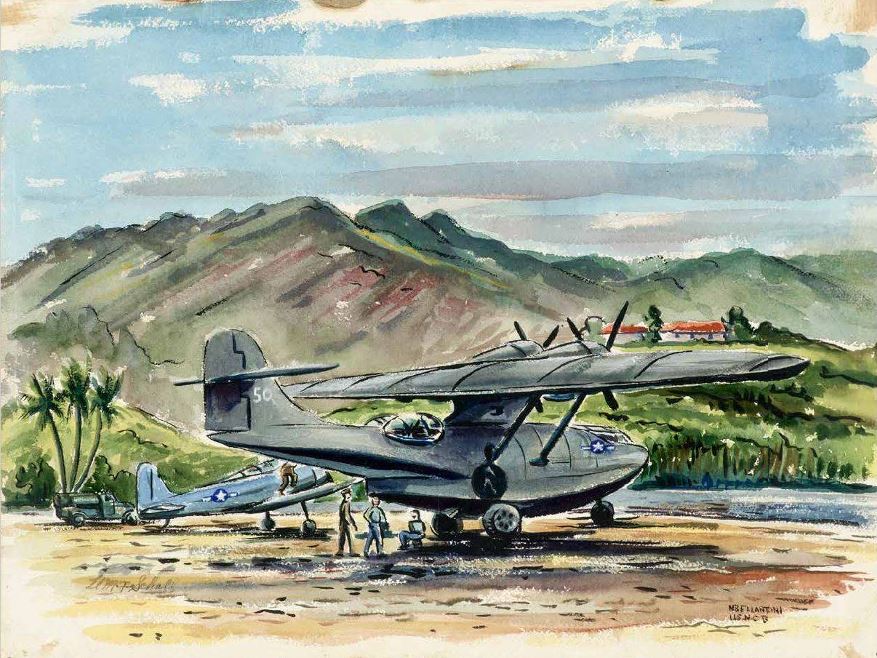

PBY50 Catalina - final journey

Admiralty Islands

Outsmarting reality with a fake photo. The dream of meeting up in the Pacific.

Leaflet to Japanese to surrender

A Wartime Selfie!

Tim Berthelette's grandfather - Boatswain's Mate 2nd class, Joseph Roderick

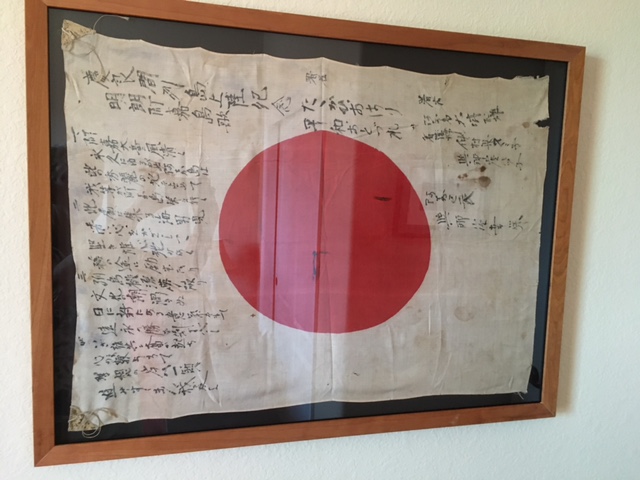

Japanese flag from WW2

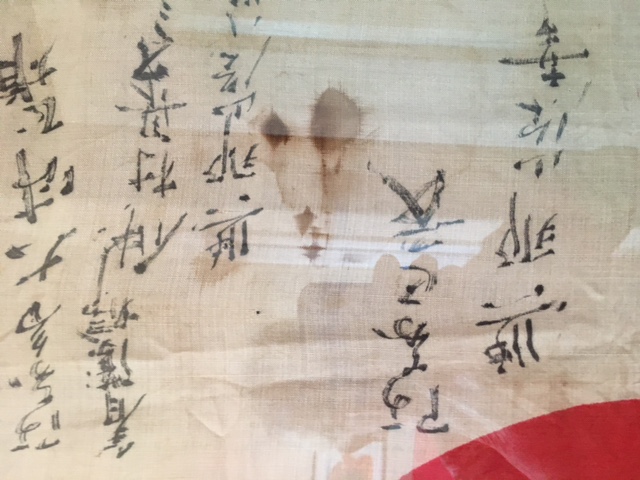

Japanese flag from WW2 - close up

In memory of landing on the string of islands between Rei Island and Ryo Island

Subtitle: A cheerful song of the Aka Island

1 The wind is fresh on Aka Mountain - the forever unshakable island of Aka!

By our conquering this most beautiful land

the land is going to prosper

- The young navy men who gather together here with one single heart

will not weaken in their courageous efforts but will go on with their duty.

- Breaking the dream - Paradise of this deserted island

the tide of culture will be swirling in it. With daily renewed strength we will

determine eternal victory

- Let us rise up all together, whipping up our drooping hearts

Let us run single mindedly towards the shore of a holy purpose

(Then a line that Nancy couldn’t translate)

The battle is ended. Peace came.

by: Masao Otau in Aka Island.

To the head of the village, Sachi Yonabuchi

Nurses Sumiko Murai Zumi and Hatsuko Yonabuchi

Fighting Through Podcast Episode 71 – The Battalion Artist,

A Navy Seabee’s Sketchbook of War in the South Pacific

More great published history! WWII

Intros

Intro Passage 1

As soon as the push across the Pacific began, the construction battalions displayed their engineering ingenuity and pluck. They struggled against unimaginable conditions and the Seabees’ baptism by fire came at Guadalcanal.

Intro Passage 2

The Seabees would be building bases so

that American troops could move forward. That, they knew. But where exactly? That,

they did not know.

Intro Passage 3

Nat strove to recreate on paper the heavy, dark intensity he felt when it was his turn to be on ship’s lookout. Time seemed to stand still but any let up in concentration was not an option, for even a moment’s distraction could cause disaster for his shipmates.

Intro Passage 4

After finishing his painting of the Patrol Bomber PBY 50, the plane took off on its mission.

Nat kept an eye out for PBY 50 over the following months ...

Welcome

Hello again and another warm WW2 welcome to the Fighting Through second world war podcast.

I’m Paul Cheall, son of Bill Cheall whose WWII memoirs have been published by Pen and Sword – in FTFDTH.

The aim of this podcast is to give you the stories behind the story. You’ll hear memoirs, and interviews of veterans in all the countries and all the forces. I dare you to listen!

A long time ago from a country far away, a lady called Janice Blake wrote to me:

Actually it was about two years ago but what’s a pandemic between friends?!

American, Janice, said “When Nancy Bellantoni and I first began to search for a publisher for "The Battalion Artist," we were told: Interest in World War II has passed its peak.

Not so!

I am discovering more and more children--and grandchildren--of World War II Veterans who are compelled to tell their father's stories.

My mother's four brothers were all in the service during the War--three overseas. I was well into a book retelling my Uncle Joe’s stories, when Nancy Bellantoni called me in 2012 to tell me her father was dying and wanted us to put together a book about his World War II paintings.

And the rest is history, as they say! So roughly ten years in the making, Janice and Nancy have finally got Nancy’s father’s works published in a magnificent volume of narratives, paintings and photographs, all depicting the war adventures of Nat Bellantoni and his naval comrades in the famous Seabees. The book has been published by the Hoover Institution Press.

And that is the subject of today’s episode.

Family stories

We also have some great family histories coming up later which feature Japanese kamikaze planes, submarines, international soccer rivalries between forces, and even more Seabee action, so do stay with me to the end. You do not want to miss the PS I’ll warn you now.

Feedback 1 - Tim

Thanks to timmygeo from USA who posted a five star review on Apple podcasts. Tim listens to the show while he drives for Uber Eats! You can see Tim’s ‘Like Riding with a Mate’ review on the FTP website. Aw thanks Tim.

Feedback 2 – Dave McNulty says

Hey Paul,

I am a 32 year old new listener to your podcast, I just want to say this channel was a gem of a find.

Being Irish I have no real connections to the world wars but my nanny who is in her late 80s, was a kid during the war and only remembers the planes flying over Glengarriff in Co, Cork. She does remember turning off lights and hiding under tables but that is about it.

Ps. My last listen was the episode 29 - Pow story with Brian Asquith, this was an amazing story. Yes it was Dave – one of my favourites and God bless the kind Polish people in that episode.

The main event:

Book intro

It’s A Navy Seabee’s Sketchbook of War

in the South Pacific, 1943–1945

78th Construction Battalion, US Navy

Published by the Hoover Institution Press

Illustrated by

Nat Bellantoni

Written by

Janice Blake

Edited by Nancy Bellantoni, Nat’s daughter.

I can't begin to describe the full extent of these paintings of the CBs in action but this episode is really about the story behind them – the CB’s.

Why are they called Seabees? Was my first question when I heard about them.

CB, Capital C, Capital B, stands for construction battalion which was fondly nicknamed the Seabees – I guess basically the busy bees who work over the seas and far away! More on that later.

And I have to say if I had just a small handful of sketches like these of my Dad going about his business in and out of action, then WOW – I would be so chuffed! As usual any pics I refer to in this episode can be found in the show notes.

Make your way to FTP.co.uk and you’ll open up a wealth of links and pics for each episode.

The Battalion Artist text

This is Nancy Bellantoni to introduce the book.

When I was a little girl, there were four watercolor paintings above a green couch,

which sat on an oriental rug in the living room of our house in the suburbs of Boston.

My family didn’t talk about the paintings much; they were just there—four colorful, small,

rectangular objects on the wall. The subject matter was exotic for 1950s America: palm

trees, thatched structures, skeletons of Quonset huts being erected, military airplanes and

ships, native islanders and enlisted men working side by side. I remember sitting on that

couch reading storybooks. Little did I realize the power of the stories in the images just

above my head, nor the proximity to history in which I was living.

My father, Nat Bellantoni, left Massachusetts College of Art in the fall of 1942, joined

the Navy, and eight months later found himself on a tiny South Pacific island in the midst

of a ferocious war with no foreseeable ending. Constantly vulnerable to enemy attack,

living and working in a bizarre and unfamiliar jungle environment, and perpetually longing

for home and his future wife, Irene, he turned to the coping mechanism he knew best.

He created a visual diary.

The Battalion Artist chronicles the wartime experiences of just one man. And yet it

reflects the story of an entire generation. More than 16 million men and women served in

the US military; 350,000 of them, like Nat, were Navy Seabees. I had the honor of meeting

some of them as I accompanied my father, then in his eighties, to reunions of the 78th

Construction Battalion in various states. These generous, strong men were proud of their

service to their country and to the world. This book is my father’s tribute to them and to all

that they accomplished.

In his role as the battalion artist, my father worked closely with the battalion’s photographer

and writers to create the Battalion Log, 78th Naval Construction Battalion, as

well as the daily newspaper, Tractor Tales. A compulsive archivist, he kept at least one

copy of every photograph snapped by Edwin Keegan, some

of his own paste-ups for the Battalion Log, a raft of Navy

documents, handouts, and mementos—both official and

unofficial—as well as gifts from native islanders and even

seashells. Seventy-five years later, when Janice Blake and I

began to plan how we would create this book, we had twenty

of his paintings, several sketchbooks, his letters to Irene,

over seven hundred photographs, and other treasures from

the 1940s South Pacific that he had saved in boxes. Sitting in

my living room surrounded by all this, Janice and I realized

that our objective was not just to write about Nat’s paintings,

but to insert all these priceless items into the timeline

of history.

It is a rare thing to experience authentic World War II

images in full color. Nat’s paintings allow us to see and feel

the colors and textures of his wartime life through the prism

of a curious and creative young man. He painted what he

saw—it was his passion, not his job. His subject matter was

his daily life: endless weeks at sea, harbors and ships, men at

work, airstrips, the local countryside, and the view of enemy

planes overhead at night from his foxhole.

As a child, I carefully studied the four paintings, memorizing

the brush strokes, the colors, and the compositions. I

knew they were from “the War.” I also knew bits and pieces

of stories, like the one about the tribal chieftain who wanted

Nat to marry his daughter and gave him a string of dog’s

teeth as a preview of the valuable dowry he would provide.

My mother wore that keepsake as a necklace on special

occasions. But mostly, there was no true context for these

paintings in my suburban life. I realize now, in retrospect,

that for my parents the paintings over the couch were symbols

of the life-changing experiences the two of them had

shared, despite the fact that they did so from opposite sides

of the world—a perennial and subtle reminder of difficult

times and of my parents’ very personal contribution to the

triumph of American democracy.

Nancy Bellantoni, Boston

DEDICATED TO IRENE,

Nat’s wartime sweetheart and future wife . . . and to all the young women who were left behind,

waiting, worrying, hoping.

I’m now going to read from the foreword section from the book to give you the back story to what’s going on. This is by

Foreward by Jean M. Cannon:

Curator for North American Collections in the Hoover Library at Stanford University

Through paintings, sketches, and photographs, Bellantoni documented the spirit and determination of the newly formed Seabees.

Almost as soon as the push across the Pacific

began, the new construction battalions gained a reputation

for engineering ingenuity and pluck. The first Seabee unit

sent overseas, nicknamed “The Bobcats,” struggled against

unimaginable conditions to build a fuelling station at Bora

Bora, in the Society Islands of the South Pacific. Following

Bora Bora, the Seabees’ baptism by fire came at Guadalcanal.

Listener, I just want to give you a brief backdrop to Guadalcanal because it was an important element of the entire war in the Pacific.

The Guadalcanal campaign, was fought between late 1942 and early 43 and it was the first major land offensive against Japan.

The Japanese defenders were overwhelmed by the Allies and made several attempts to retake the airfield – later called Henderson Field.

Many land naval and air battles culminated in the decisive Naval Battle of Guadalcanal in early November 42, with the defeat of the last Japanese attempt to bombard Henderson Field from the sea.

The enemy were completely out of it by early February 1943,

So - Upon their arrival on the island, the [battle-seasoned] Marines [who were already there] at first made fun

of the “old men” (“Say, pop, didn’t you get your wars mixed

up?”)

The newly formed Seabee battalions

lacked organization and established service traditions – [so they weren’t]

“construction battalions” but “confused bastards,” joked the

young Marines).

The unfolding events on Guadalcanal—and

particularly the building of Henderson Air Field under heavy

fire—soon redirected the Marines’ attitude from drollery to

reverence.

[The Seabees] soon proved they could organize and execute

the seemingly impossible engineering feats that allowed

the Marines to continue their battle across the Pacific and

into enemy territory. Not only did the Seabees rehabilitate

Henderson Field from a mud pit to a first-class airfield,

they built docks to unload supplies from ships,

[They] cut millions of feet

of lumber to build barracks and warehouses,

drained swamps

in order to fight off mosquitoes and malaria,

and constructed

hundreds of miles of roads on the island.

Under heavy enemy

fire, the construction battalions coordinated so efficiently

that one hundred Seabees could repair the damage of a five

hundred-pound bomb strike on an airstrip in forty minutes,

completely flummoxing Japanese bombers and no

doubt damaging the enemy’s confidence in its air power.

After quickly and skillfully building the machinery necessary

to maintain the base at Guadalcanal, Seabees could

be heard sportingly reporting to their Marine chums that

the construction battalions had been sent “to protect these

helpless Marines.”

Inter-service heckling continued after

Guadalcanal, but with grudging respect on both sides. The

Marines and Army may have driven the Japanese off the

island, but it was the Seabees who ensured that Americans

could stay and prosper, supplying everything

from ammunition magazines to a “Tojo Ice Company” that

provided cool drinks to soldiers in the jungle heat.

After the incredible achievement of establishing a

structurally sound runway and base at Guadalcanal, the

Seabees continued across the Pacific.

They suffered long weeks at sea headed toward

unknown destinations (Bellantoni painted many scenes en

route to what his battalion called “Island X”), hostile climates,

bombardment, and exposure to dangerous diseases.

Jean M. Cannon.

So with that backdrop I’m going to cover what happened to young Nat. He was commissioned Feb 43 and after training, by June that year he was on his way …

CH A P T E R 1 - UNDERWAY:

ABOARD THE MS DAY STAR

June 16, 1943.

The MS Day Star, with the US Navy’s 78th Construction Battalion aboard (more than one thousand men), slipped away from the dock at Port Hueneme, Why Nee Mee,

California, and headed for the open waters of the wide Pacific. The battalion band

struck up the brave chords of Anchors Aweigh. It had taken all morning for the men

to board the ship, each one lugging his field pack and weapon, trench shovel and

machete, plus the gear and tools that would be essential to his work.

In addition, Nat Bellantoni tucked in among the skivvies and the crisp new uniforms a

clutch of small spiral-bound sketchbooks, a tablet of art paper, a supply of artist’s pencils,

and a box of watercolors. With these—in addition to whatever he was called upon to do by

the Navy—he would fight the war on his own terms.

FUTURE UNKNOWN: ISLAND X

Spread over thousands of miles of open ocean were countless well-fortified islands still

in enemy hands. Many of these would have to be taken before the Allies could begin a final

assault on the Japanese homeland. The members of the 78th would be building bases so

that American troops could move forward. That, they knew. But where exactly? That,

they did not know. On this cruise, and every time hereafter that they boarded a ship for

a new assignment, the most they would be told for certain was that they were headed for

Island X. You know that so typifies my Dad’s experience in the war. I’m sure the authorities kept things secret as far as possible as a matter of policy.

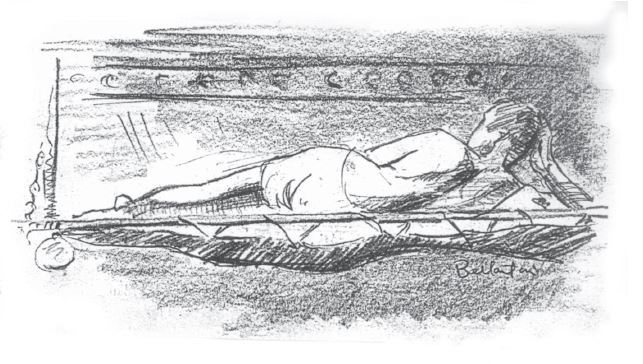

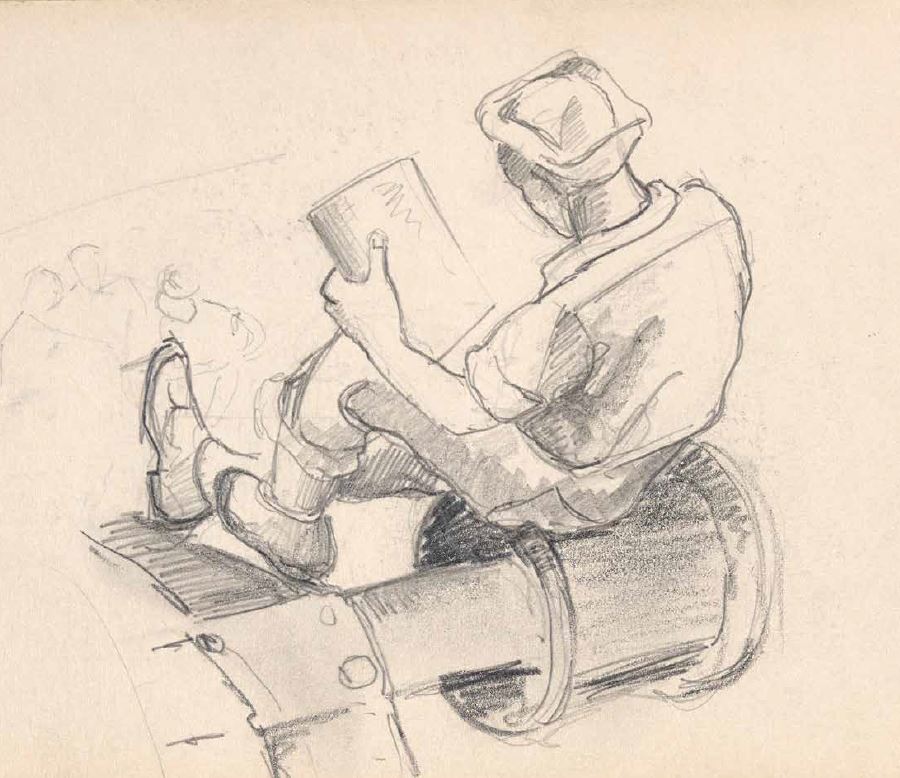

(pic of rivets in bed)

At this point, I’d just like to interject with a passage from dads memoir from when he was on the Empire Lance sailing over to France the night before D-Day. I think the narrative goes perfectly with a painting from Nat.

The paining is of a lone sailor on his bunk, facing the rivets on the side of the ship and I’m sure this depicts what dad described in his book. It no doubt reflects the thoughts which were also going through the minds of the Seabees. Of course Nat and his pals would have no idea what might become of them –they know they’re on their way to dangerous waters but they have no idea what to expect

This is what Dad wrote:

Few of us slept on the night of 5 June. Our thoughts were completely monopolised

by what was going on around us and the thought of what tomorrow might bring. Most

of the boys were very quiet, keeping their thoughts to themselves as we were well

aware that a good number of us would be killed and the suspense was awful. We were

facing the unknown, tomorrow, and the estimate of casualties did not improve the way

we were thinking.

Fortunately they were widely exaggerated, but could so easily have

come true and were still bad enough. Many lads wrote letters to be posted after the

invasion had started.

Others went to their hammocks early and turned their backs to

others, to be with their thoughts – alone – thinking about the loved ones they had back

home, saying a silent prayer that God would keep them safe.

Alone in his bunk at night, as the engine droned and the

hull occasionally creaked, Nat often thought back to those

frightening first weeks of the war, to the newspaper headlines

and urgent, grim voices on the radio: Pearl Harbor.

Luzon. Corregidor. Bataan. Nat recalled how his father

sometimes shook the morning paper while he was reading,

as though to catapult the bad news right off the page.

After months that brought only shock, anxiety, and

grief, the tide began to turn. There was the Doolittle Raid

on Tokyo, the Battle of the Coral Sea, and then Midway—

heralded as Japan’s first decisive military defeat in over a

century. Nat remembered how his mother had stood up and

cocked her ear toward the radio when this good news came.

A slight smile supplanted the look of worry that seemed to

have given her a perpetually furrowed brow.

At this moment in time, June 43, nearly a year after the Battle of Midway, the Japanese still

controlled the vast oil reserves and rubber plantations

of the East Indies and Southeast Asia. They were firmly

entrenched in northern New Guinea.

True, the US Marines

had long since pushed them off Guadalcanal in the Solomons,

but it had taken seven months of gruesome struggle. And

the Japanese still held dozens of strategically vital islands

across the Pacific.

The Seabee motto was “Can Do!” And always, before finally

falling asleep, Nat would think about what he would be asked

to do . . . could do . . . would do. And by visualizing action, he

pushed back fear.

SCANNING THE HORIZON

The vast Pacific Ocean covers more than 60 million square

miles, more than a third of the Earth’s surface. The distance

between Port [Why nee mee] Hueneme and the Day Star’s destination—

the island of New Caledonia off the coast of Australia—was

more than 6,200 miles. The men of the 78th Battalion would

be at sea four weeks. But Nat, like his buddies, was unaware

of these statistics. They did not yet know where they were

headed or how long their voyage would be. They would find

out where they were going when they got there.

For now, what Nat and the rest of the Seabees did know

was that they were jammed together in crowded quarters,

that the days were long and the routines were fast becoming

tiresome.

They slept in bunks stacked four high and took turns to eat in the mess because there weren’t enough seats for all of them to sit down at the same time. The Day Star

was a Danish ship, captured from the Germans and refitted

as a troop transport. The Danish crewmen had stayed with

their vessel and now criss-crossed the wide Pacific endlessly,

bringing to its far reaches the men who were freedom’s last,

best hope to turn back the Japanese tide of brutality and

aggression—sailors, Marines, soldiers, and these Seabees.

As the ship cruised westward, the only thing the men

knew for certain was uncertainty. They were sailors aboard

a ship and so were vulnerable to surprise attacks at any time,

from bombers in the air or submarines under the sea. Their

first challenge, then, was to stay alive. And so, around the

clock each man took his turn at lookout.

Endlessly scanning the horizon for enemy craft was a

tedious assignment. Nat strove to recreate on paper the

heavy, dark intensity he felt when it was his turn to be on

watch. Time seemed to stand still. Any change in the look

of things—even the warm glow of the sky at sunup and

sundown—felt ominous. Certainly, taking a moment to

enjoy the beauty of the dawn would be wrong. Any letup in

concentration was not an option, for even a moment’s distraction

could cause disaster. Each man knew that when

he was on watch, his shipmates were counting on him, and

him alone.

You know I’m absolutely fixated by the issue of taking turns at lookout. Dad mentioned it several times and it was like – some variation of so many hours on and off …

On the evening of D-Day, the company settled down after the excitement and trauma of the day and it was

my turn to do guard with another lad – two hours on and two hours off, which was

different to the usual two hours on and four hours off. In a situation such as we

were in, it was always essential to be constantly on the alert. Being on duty in pitch

dark, when every move is magnified out of all proportion and a knife in the back is a distinct possibility, keeps a lad on his toes, every nerve straining for the sound of an

enemy patrol. They too, would be silent, listening for the slightest giveaway sound!

clearly similar except he’d be looking for either other ships or maybe the giveaway trace of a deadly torpedo heading silently towards them. Such was the responsibility upon people that Dad said they were given the day off before and after lookout duty to make sure they were well prepared and recovered. Wow!

And all this just reinforces the serious trouble the late veteran Wilf Shaw would have been in if he’d been caught shooting up the latrine the way he did in stories we’ve heard before.

So here’s Nat’s experience …

GUN WATCH (Pic)

Although nobody ever spoke of it, the men aboard the Day

Star well knew that the very water on which they sailed

had absorbed and dispersed the blood of untold numbers

of their comrades in arms. When the light cruiser USS

Juneau was sunk off Guadalcanal back in November 1942,

687 men were lost, including five brothers—the Sullivans.

In March 1943, while the 78th was still training in Gulfport,

Mississippi, American and Australian planes had attacked

a Japanese convoy headed for New Guinea with troops and

supplies. Eight troop transports and four destroyers were

sunk; more than three thousand enemy soldiers and sailors

were killed. Of the 150 fighter planes escorting the convoy,

102 were shot down.

This stunning Japanese defeat would be remembered

as the Battle of the Bismarck Sea. With it, the blood of

the enemy also poured into the waters of the Pacific. In

April, US code breakers had discovered the whereabouts

of Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, mastermind of the Pearl

Harbor attack; P-38 fighters succeeded in shooting down

his plane. So now, the blood of Yamamoto himself had been

spilled in this vast ocean.

Nat thought about the nature of the enemy most often

when he was on gun watch, and he knew it was the same

for his buddies. Gun watch somehow felt even weightier

than lookout duty. Scouring the horizon with binoculars

was a huge responsibility, true. But if the lookout did spy an

attacker, the men on gun watch knew that in that first instant

of encounter, they were all that stood between the ship (and

their shipmates) and utter destruction.

The antiaircraft gun, poised for action, was always

echoed in the stance of the men beside it: alert, decisive, and

ready. From the deck below, Nat was impressed with how

this scene—awash in blues, grays, and greens that blended

with sea and sky—was somehow reassuring. With those two

men standing firm in the solid geometric mass of the turret,

it seemed that every element of the ship was calm, confident,

and capable, that even the taut cables and sturdy life

rafts would spring into action almost of their own volition in

support of these two men: two men who, for this four-hour

watch, held all lives aboard in their hands.

If you can, take a quick shufty at the FT web site and you’ll see that very scene. I’m imagining the crew in charge of the gun about to spring into action as they shout a warning that there’s an enemy ship on the Starboard bow!

KP – Kitchen Patrol

At sea, the biggest challenge for all the men was to keep

worrisome thoughts at bay. So when Nat was off-duty, he

did all he could to keep his own spirits up and to help his

buddies do the same. They all worked hard to cheer up,

distract, and entertain one another. There was always

something going on, from card games to impromptu

competitions—whether arm wrestling or seeing who could

down the most pie. There were recitations of each man’s

best-remembered jokes and tall tales. There was good-humored

teasing and talk of home.

Somehow, kitchen patrol, or KP, helped bring that talk to

life. Gathered on deck just outside the galley—peeling potatoes

or pulling the tough outer leaves off heads of cabbage—was

nothing like strolling through Ma’s kitchen. Yet there was

something about the familiar routines of food preparation

that evoked warm memories of home. Most men grumbled.

They would rather be catching a few extra winks, reading a

detective magazine, or enjoying a smoke and daydreaming

about their sweethearts.

[When I see Nat’s painting of KP I’m reminded of Dad’s experience as Officer’s cook, and his mention of the 252 charge for breach of discipline with the punishment being Jankers – often cookhouse duties such as peeling spuds!]

NOUMÉA, NEW CALEDONIA

Finally, Island X had a name. After four weeks at sea, the 78th Construction

Battalion was preparing to disembark at Nouméa in New Caledonia.

About

nine hundred miles off the coast of Australia, this sleepy colonial port was

rapidly being transformed into a base that would serve as headquarters for

the South Pacific Command. The camp at Magenta Bay, the

jumping-off point for thousands of soldiers, sailors, and Marines heading to

duty at forward areas, was just beginning to take shape on the low, rolling hills

that surrounded the little city. It was July 13, 1943.

The men of the 78th would join other Seabee units working

to expand this camp. They would grade landing strips;

build warehouse, administration, and hospital buildings;

construct storage tanks and plants for filling fuel drums; and

install pipelines.

With his unconventional set of skills, Nat’s assignments

were more varied than most. Often, he worked as a draftsman.

Usually, he would be the one to hand-letter the simple signs

that identified buildings and provided directions on roadways.

Always, he served on the staff of the battalion newspaper.

Sometimes, he created artwork for interiors as different as

officers’ clubs and chapels. Occasionally, he would be called

upon to solve a crucial camouflage problem. Eventually, he

would contribute to one of the legendary morale-boosting

programs of the war—painting nose art on the fuselages of

Navy planes. These included humorous cartoon figures, clever

names in bold lettering, and Alberto Vargas–style pinup girls.

Often, it didn’t really matter what his rate or rank was. He

would simply lend a hand where needed.

The sun was warm but the breeze was cool and dry as

the men on deck waited impatiently for gangway lines to be

secured so they could hit the beach. Maybe it won’t be so bad,

Nat thought as he shouldered his seabag. But maybe it will

be worse than my worst nightmare. The tangle of shuffling

men began to move. Maybe I will come out of all of

this okay. He

stepped resolutely onto the slightly swaying gangway. Maybe

I won’t come out of this at all. Suddenly, his feet in their heavy

work boots were firmly planted on solid ground for the first

time in four weeks. Maybe I should just stop thinking. It was

time to get to work.

FINAL JOURNEY (Pic)

It was an afternoon like so many others when Nat, with some free time, set up his easel.

What caught his eye this time was a PBY Catalina parked on the hardstand beside the

airstrip, its crew nearby. PB stood for Patrol Bomber, the Y a code for the manufacturer, Consolidated Aircraft.

These versatile planes, when painted black, were deployed—

usually at night—to stalk enemy shipping. In addition to reconnaissance, they were also

sent to rescue downed American air crews. Sleek, silent, and stealthy, they were nicknamed

Black Cats.

With a very slow cruising speed—around 150 mph—Black Cats were easy targets for

enemy planes. Although it was risky, they often flew low to be less conspicuous.

After finishing his painting of PBY 50, Nat decided he’d like to get the skipper to sign it.

He walked over to the plane and found Lieutenant Merle Schall, who was happy to oblige.

If you take a look at the pic on the web site you’ll see that Schall did indeed sign the painting in the bottom left corner.

While his crew was getting the Cat ready for takeoff, Schall chatted briefly with Nat, who

promised to get a photo made of the painting for the pilot to keep. They shook hands all

around and said they hoped to meet up again. It was August 1943. The 78th remained at

Nouméa until late November. Throughout those months, Nat kept an eye out for PBY 50.

Correspondence

On January 11, 1944, Nat sent Lieutenant Schall a note,

enclosing two black-and-white prints of his painting. Less

than a month later, he received a reply from the young pilot’s

mother. Mrs. Schall thanked Nat for the pictures of her son’s

plane and explained that his note had been forwarded to

her because on the night of November 6, 1943, PBY 50 had

been lost. While turning at a very low altitude, the plane had

caught a wing in the water and crashed. Two crew members

had survived. Lieutenant Schall was not one of them.

Listener if you want to find out what happened here, stay airborne for the PS coming later.

C H A P T E R 3 - MILNE BAY, NEW GUINEA

The USS Maui, a converted luxury liner, transported the 78th Construction

Battalion to its next Island X. After five days of zigzagging to avoid Japanese

patrols—west to the coast of Australia, then back across the Coral Sea—the

Maui finally anchored in Milne Bay, on New Guinea’s eastern tip. Massive

transport vessels drew alongside. Men and cargo were quickly transferred

and within days were headed north along the coast. They passed Buna, where

the fearsome battle over the treacherous Owen Stanley track had ended,

finally, in Japanese defeat. Under drenching rains, they headed across Huon

Gulf at night.

SURROUNDED BY FIGHTING

Even as the men were making their way ashore, Australian

troops, just a few miles away, were driving the enemy northward.

The men could hear guns in the distance. But they

had no time to stop and listen. Their first task was to unload

their equipment and supplies. This took several exhausting

days and nights, with all hands sleeping in the open and food

prepared camp-style using improvised cooking facilities

until a proper mess hall could be constructed.

The men were soaked at least once a day, nearly every

day, by tropical rains. They were always surrounded by

the distant booming of artillery, the oppressive heat of the

jungle, mud (lots of it), mosquitoes (plenty of them), and

the invisible threats of malaria, dengue fever, jungle rot, and

dysentery. For a while, the 78th was operating farther north

than any other American unit in the South Pacific. Air alerts

occurred every night and several times each day, sometimes

followed by falling bombs.

ADMIRALTY ISLANDS – pic

Once it became clear that Japanese forces would be driven off New Guinea,

the Allies set their sights on the Admiralty Islands two hundred miles north

and east. The Admiralties offered plenty of space for a major US base and an

ideal strategic position for moving north.

It was March 1944.

On the other side of the world my Dad was in Scotland getting ready to invade France on D-Day, 6 June! So all the Allies were doing their bit for the collective defeat of Hitler and Hirohito. That trust and teamwork amongst the allied countries is quite breathtaking.

The 78th Construction Battalion was transferred to these islands in

several waves. Those who arrived first found that the area assigned to them for bivouac had

been a battlefield only a few days earlier. They saw destruction everywhere—abandoned

foxholes, huge bomb craters, splintered palm trees, ruined equipment, even enemy dead,

not yet buried. Just a few hundred feet away, artillery was blasting away at Japanese fighters

who were stubbornly holding their positions. Nat took a long, slow look around, then

tossed his seabag aside. So this would be it—his third Island X.

And there’s a photo in the show notes of this scene of destruction.

Outsmarting reality – pic

The men of the 78th worked their fastest, barely stopping to eat and sleep. They knew that

the Army, Navy, and Marine Corps were all waiting. As soon as this base was operable, battles

would be launched. Every man pitched in. Rate and rank and regular jobs were irrelevant.

For every day’s delay, the Japanese were building more pillboxes, reinforcing more bunkers,

booby-trapping more beaches. The days passed quickly. Yet, somehow, the months did not. It

could take weeks for a letter to leave Nat’s tent in the South Pacific and arrive at Irene’s home

fourteen thousand miles away, and weeks more for him to receive her reply.

Nat daydreamed about finding a way to magically cross all those miles. A grass skirt

purchased from one of the islanders sparked an idea. Nat sent it to Irene and she sent back

a snapshot of herself [wearing it]. Meanwhile, Nat had wrapped himself in a native sarong and asked a buddy to

take a picture [of him].

With both photos in hand, all it took was a little darkroom magic. There they

were together! It was fun. It was romantic. But . . . it wasn’t enough.

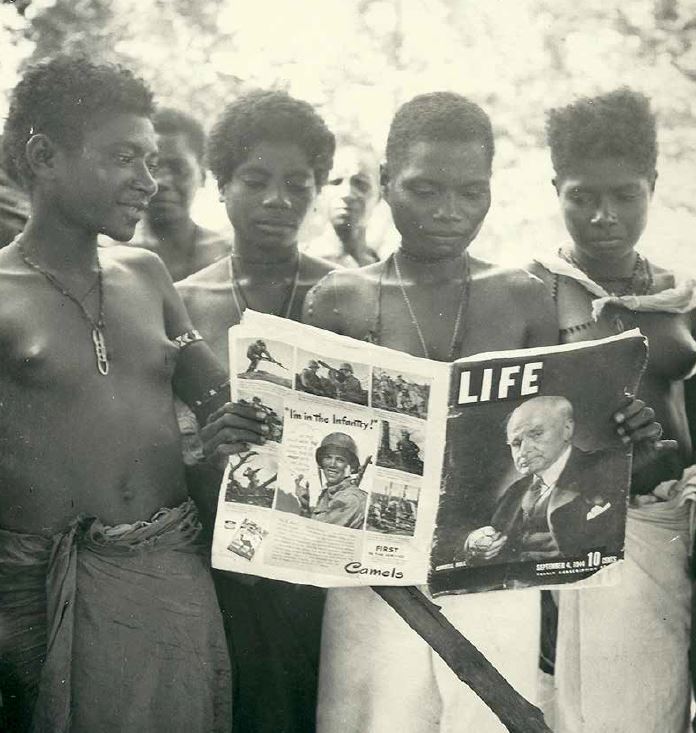

Hitchhiking—South Pacific style

Throughout the South Pacific, the islanders were eager to

help the US Navy defeat the Japanese. They often served

as porters, scouts, messengers, and able seamen. They used

their outriggers to transport men and supplies to landing

places too shallow for Navy longboats. In return, US sailors

were more than willing to assist the natives when and how

they could.

One of the easiest things the sailors found to do was to

provide an impromptu towing service. An islander who saw

a Navy launch overtaking him would wave. The Navy boat

would slow down and throw out a towline. With the line

secured, the outrigger would zoom along. As he approached

his destination, the native skipper would signal. The Navy

boat would slow down, wait for the line to be released, and

then speed away. The crews of both boats would be left smiling.

These simple encounters were a welcome distraction

from the grim business of war.

6 - UNDERWAY: ABOARD –

THE USS J. FRANKLIN BELL

In late April the orders finally came. The 78th Construction Battalion would

be moving out to yet another Island X. Although there was never an official

acknowledgment, Nat knew exactly where the 78th was headed. They all did.

As the 78th construction battalion scrambled

aboard the Franklin Bell, there was a sense of

restless energy in the air. After five months of

working at a pace that had fallen into easy routine,

the men were once again filled with both eagerness

and dread. Determined since the beginning to do

all they could to help win the war, every man knew

they would never reach that goal without a long,

tough, dangerous, and exhausting stint on one last

Island X. They would need to build the massive

base that would take the war to its inevitable final

end point—the base that would enable fighting men

to launch an invasion of the Japanese home island.

They were headed for Okinawa, where ferocious

fighting was already underway.

8 - FINALLY, IT WAS OVER

At 2:45 a.m. on August 6, 1945, the B-29 Superfortress Enola Gay lifted off

from North Field, Tinian Island. Five hours later, with Hiroshima’s Aioi

Bridge aligned in the crosshairs of his Norden bombsight, the plane’s bombardier

released its unimaginable payload, the first atomic bomb ever exploded

over a populated city. The world would never be the same.

On August 9, a second atomic bomb was dropped on the

city of Nagasaki. And the Soviet Union, having declared war

on Japan the day before, invaded Japanese-held territories

in Mongolia, Korea, and several North Pacific islands.

On August 15, in a radio broadcast marking the first

time he had ever spoken directly to his subjects, Emperor

Hirohito announced Japan’s acceptance of the Allies’

demand for unconditional surrender.

Japan’s war had cost nearly 20 million Asian lives, more

than 3.1 million Japanese lives, and more than sixty thousand

Western Allied lives. Finally, it was over.

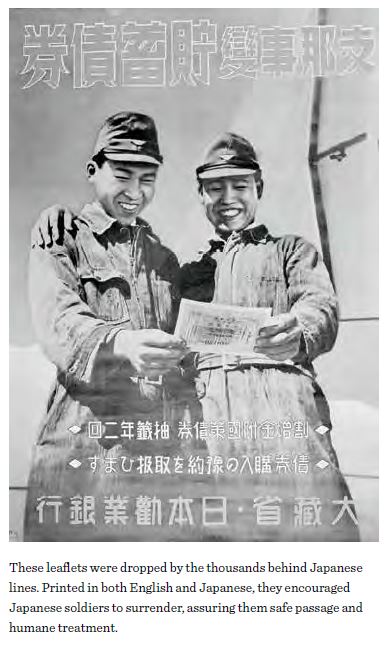

Leaflets were dropped by the thousands behind Japanese

lines. Printed in both English and Japanese, they encouraged

Japanese soldiers to surrender, assuring them safe passage and

humane treatment. (Pic)

HEADING HOME

At long last, Nat and the men of the 78th Construction

Battalion were heading home, with seabags on their shoulders

and pride in their hearts. Their achievements were now

a part of history.

Over the previous three and a half years, the US Navy’s

Seabees had constructed 111 major airstrips, 441 piers, over

2,500 ammunition magazines, hospital capacity for 70,000

patients, 700 square blocks of warehouses, housing for 1.5

million troops, and storage tanks holding 100 million gallons

of gasoline. The Seabees in total built more than four

hundred bases. Eighteen were major facilities constructed

at a cost of more than $10 million each (in World War II–era

dollars). Fifteen of the eighteen were in the Pacific theater;

of these, twelve were in strategically crucial locations that

had to be wrested from the enemy. This meant that mountains

of rubble—the debris of battle—had to be cleared away

before building could [even] begin.

The Seabee motto was, and remains, We build. We fight.

Their slogan is [STILL] “Can do!” It is no exaggeration when considering

the history of World War II to say that the Seabees

truly built America’s victory.

Nat Bellantoni would ever after be proud that he had

been one of them.

[Nat soon found himself in the queue at the Naval Separation centre …]

Bellantoni! Bellantoni?

Nat heard his name. He shook himself back to the here

and now. It was time to step forward. Within moments he

had the precious paper in his hands: honorable discharge. It

was stamped. It was signed. Now he could breathe freely. He

could plan for the future. Just four days ago—still an active duty

Seabee—he had married Irene. He would get a job. He

was going to be an artist. He was going to have a life. And he

was going to enjoy every moment of it.

It was time to go home.

On January 6, 1946 Nat married Irene Sztucinski, whose love and letters had sustained him throughout his long months

at war.

Together, Nat and Irene settled down in Reading, Massachusetts. They raised three

children: Stephen, David and Nancy.

[Me:

“He didn’t know then that that little Nancy would grow into big Nancy and write this book of his amazing Adventures!]

Once the war was won, Nat returned home and had a successful career

as an art director in a prestigious downtown Boston firm. His boxes of wartime memorabilia

were stored away, seemingly forgotten, as the decades passed.

Now, with his children grown and his mortgage paid, Nat began to reconnect with old friends and old memories. At age 91, he dreamed of sharing his wartime story. This book is the fulfilment of that dream.

I’ve got to thank Janice Blake for bringing this lovely book to my attention and for her efforts in so skilfully narrating the story behind the paintings and escorting us through Nat’s war. Thanks to the late Natale Nat Bellantoni for his precious artistic contribution to wartime history and to daughter Nancy who edited the book … edited – such a simple word for a hugely time consuming and important task that I expect took some years – but I’ll bet it was the most wonderfully cathartic journey for you Nancy – well done that gal!

And Janice, has tipped me off to the fact that Nat's entire collection of artwork, papers, and memorabilia from World War II, resides at the Hoover Institution Library and Archives at Stanford University. Search for Hoover digital collections or use the links in the show notes.

Nat Bellantoni died on June 23, 2012. He was buried

with full military honors—a Seabee to the end.

Clearly the girls who put Nat’s story together had time to explore it with him.

Wife Irene died four years later in 2016 aged 95

https://www.legacy.com/us/obituaries/bostonglobe/name/irene-bellantoni-obituary?pid=183211729

My close

So there we go. There are plenty more adventures where these came from. If you buy the book you’ll learn more about how the Seabees built a cathedral for some of the islanders, nearly drowned in drenching rain storms, played cat and mouse with enemy patrols, how they worked under threat from Japanese Kamikaze pilots, how they sometimes succumbed to deadly diseases, and got bogged down in muddy quagmires as Nat and his comrades in armoured bulldozers risked their necks to move the US army closer to that fateful final island, Okinawa, so the Seabees could complete the road from Pearl Harbour with one last push to the home of the enemy who had been so ruthless in their execution of war.

Search lights, bombed bridges and burial vaults all feature on Nat’s canvas in the lead up to that final pay day, August 6th 1945, a shiver just went up my spine. And there is one final secret bonus role played by Nat when it comes to the Japanese surrender.

My sincere thanks to Janice Blake for getting in touch and for her and Nancy Bellantoni’s hard work in getting the book to publication. Janice said she spent two years just researching before she began to write the book and the first version even included a complete history of the War in the Pacific...which they eventually left out.

This book is a unique record of scenes you just never get to see in your average book. I’ve put several images in the show notes and you can obviously buy it from all good book sources.

And Janice Blake, has tipped me off to the fact that Nat's entire collection of artwork, papers, and memorabilia from World War II, resides at the Hoover Institution Library and Archives at Stanford University. Search for digital collections or use the links in the show notes.

https://digitalcollections.hoover.org/search/bellantoni

https://histories.hoover.org/battalion-artist/

So if you want to dip into it all and learn more before buying the book then it’s a possibility. If you want a treasured memento of Nat’s war and the Seabees, you’ll need to get a copy of The Battalion Artist, available from your usual bookseller.

Do you want more?!

Oh go on then – actually I’ve got stacks more to share, especially some amazing family stories related to the Seabees..

I haven’t finished the story about the PBY50 Catalina yet – well as I said earlier – keep airborne Captains! All will be revealed.

Family stories - Tim Berthelette

Has written in with a wealth of family history and not only does it start brilliantly, it gets better and better! I’ve been keeping this for ages now to tie it in with the Seabees episode I was planning.

Hi Paul,

Greetings from across the Pond. I've been a big fan of your podcast since 2017. I have several members of my family that were in the War. My great Uncle John was a B-24 pilot. he was a member of the 446th Bomb group in the 8th airforce. He was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross for bringing his badly damaged plane safely home, saving both the plane and several of his wounded crewmen. My great Uncle Al was in the Navy somewhere in the Pacific. During his service, he became his ship's Barber and used his skills to open his own successfull Barbershop after the war. Both passed away before I was born and sadly their stories and service histories were lost to time. Tim I do wonder how many close shaves he had!?

My Grandfather was Joseph Roderick. After being turned down by the Marines and Army for having flat feet, He was able to join the US Coast Guard in 1942. His initial duty was horseback beach patrol on the US east coast. Armed with only a .45 pistol and a WW1 vintage rifle, he was tasked with looking for signs of U-Boat activity and saboteurs.

The highlight of his service was helping survivors of several ships sunk by U-Boats, victims of the Kreigsmarine's Operation Drumbeat.

In 1945, He began training as a landing craft crewmember in preparation of the proposed invasion of Japan. Thankfully that never happened and he returned to civilian life in 1946. He never talked about his service, as I believe he had guilt about surviving when he had lost many friends.

I have many fond memories with him as a youth, camping, fishing etc. I never really asked him about his service. It wasn't until many years after he passed that I discovered his medals and some mementos of his service which I display proudly in a frame.

It was his inspiration that lead me to choosing to enlist in the Navy. The proudest I've ever seen him was upon my graduation from Basic training. Sadly, he passed before I really got a chance to discuss his experiences.

I have a memory from my own service, which you might enjoy. In 2017 I was deployed to Northwest Africa in support of Special Operations. Near our camp was a French Army camp, with a contingent of your countrymen stationed there. I believe they were members of the Para Regiment. It was one of those lovely Chaps who introduced me to your podcast.

At one point we had used some of our heavy equipment to clear a field next to camp for sports and exercise. We invited our French and British comrades over to enjoy it as well. We spent many enjoyable hours in fierce but friendly competition. Both sides trying to prove who has the better version of "football". We just couldn't fully embrace British Soccer to be competitive. One of the Paras said "American Football is rubbish, it's for little girls who can't play Rugby" I hope that made you laugh as much as I still do thinking of those days.

Oh dear – pause for laughter from all sides of the audience. Do you know - so many times during this show I’m brought back to the memories of Audrey Johnson in episode 33 Women at War where there was so much ritual mickey taking between the Yanks and Brits - if you haven’t listened to episode 33 about the WREN stationed in Northern Ireland, you really must.

Attached is a photo of my Grandfather USCG Boatswain's Mate 2nd class Joseph Roderick and his awards. Thank you for your time and please keep up the amazing work on the podcast.

Tim Berthelette

Massachusetts, USA

United States Navy

Pic on file

Tim added, unwittingly correcting something I said earlier …

The Navy Seabees have a long proud history since March 1942. They got their name from the military abbreviation for Construction Battalion, shortened to "CB". Walt Disney actually drew up a cartoon Bee complete with a Sailors hat. Tommy gun in 1 hand and tools in the other.

Henceforth, CB became Seabee. have you ever seen the movie, The Fighting Seabees? Once you subtract the hollywood flash and typical John Wayne braggadochio the script is actually based on the real details of how the battalions were formed. They came about because unarmed civilian contractors were being captured and killed by the Japanese as they steamrolled across the Pacific in 1941. Most units were scattered across the Pacific. Groups landed on several Islands in the first few waves with the Marines. There were even Seabees in Normandy.

Braggadochio (wow – what a word – love it – braggadochio – it means cockiness or boastful swagger. I bet Paulo Bonini ..?

Tim continues: I served in the Seabees from 2002-2017 as a Mechanic of Heavy Equipment. 4 years active duty and the rest was Reserve time. I've had several deployments including convoy security in Iraq and the one to Africa for a camp maintenance assignment that I mentioned earlier.

Tim – thanks you so much for all that – and sent in with all the great timing that surpasses that of a soccer centre forward.

Family stories - David Money

Hello Paul,

My Grandad on my Dads side was John Edward Money and during the war he worked on an air force base in England and my dad believes he was a LAC (Leading Air Craftsman??). My uncle believes he sometimes worked on a US Air Force Base and pulled dead bodies out of the bombers (no way of confirming this). My dad always remembers has dad telling him “I’ve seen aeroplanes you will never see (he has always told me this sentence whenever I mention WWII. I was born in 1973 and he had passed away before then but I know he survived the war I just never met him.

My uncle was William Money (Bill) and was in the royal navy on HMS Millen (believe this to be the ships correct name) and was on the convoys to Russia and I have been told he was on a ship off the coast of Normandy on D Day but that bit may be incorrect.

Unfortunately there has never been anyone in my family who was able to give me more information and there is no shred of memoires or even photos that I have ever been able to find.

War stuff 1 Dan Carlin

Shout out for Dan Carlin in his latest stupendous season from the Hardcore History podcast – called Supernova in the East.

Dan voice for drama comes into good effect again as he rolls out a series that, by sheer chance, perfectly complements the memoirs of Australian Veteran Les Cooke, which I’ve recently covered.

You can start Supernova at episode 63 but if you want to pick up on the part relating to Les Cook’s memoir, join in at episode 66, though if you’ve not heard Hardcore History before I promise you’ll be re-joining again at the very start.

So if you want an insight into the brutal backdrop to Les Cook’s experience in New Guinea and more, leading to the final defeat of Japan, plus indeed a perspective on the entire Pacific war, listen to Dan’s Supernova series episode 63 onwards of Hardcore history.

And Dan does not pull any punches so be prepared to be shocked.

Round up

Thank you so very much for your support and for making the time to listen to me.

And please - write, like, rate, review or share the show - howsoever it pleases you. Above all – enjoy. Please do hear me next time. Hey – aren’t we having fun with the FTP!

And if anyone has any Christmas at War stories, please do get in touch because I’m gradually getting memories together for a Christmas special in December. It doesn’t have to involve bombs and bullets, more crackers and contraband. But anything goes really.

Is there any snow on the ground? That’ll do nicely!

There’s a PS coming up about Nat Bellantoni’s missing Catalina aeroplane, and an extra bonus, extra long, PPPPS or 4PS as the man in the clothes shop might call it. It’s a memoir from John Serra from the Seabees which Nancy Spencer who I mentioned earlier sent in. John was her father.

And if the mention of Jap submarines, Kamikazis and ice cream machines gets you salivating, then you need to listen in. This memoir is an absolutely perfect complement to Nat’s stories, believe me. I actually can’t believe my luck at the timing of these things being sent. I did put all the girls in touch with each other so I think they’ve been able to have a good old chin wag about the Seabees.

PPS – PBY50 Catalina

Oof my word.

You’ll recall earlier I introduced the story of the Patrol Bomber that Nat had painted but never saw again, and with the sad revelation from the pilot’s mother that her son, Merle Schall, had died when the plane crashed. Under normal circumstances that would have been the end of matters except:

In July 1997—more than five decades later—Nat received a

phone call from Michael Schall, Merle’s nephew, who was

writing his uncle’s biography and had some questions. He

told Nat he was not satisfied with the Navy’s report about

the crash and was hoping to get more information. Nat

answered Michael’s questions. They began corresponding.

Michael Schall eventually connected with PBY 50’s

two surviving crew members, who told him it was a Navy

destroyer, the USS Renshaw, that had rescued them. The

plane had been on a lookout mission over Empress Augusta

Bay, in the Solomon Islands, when it went down. The airmen

were to watch for approaching enemy ships or planes in

order to protect the night-time landing of Marines going

ashore on Bougainville Island.

In February 1998, Michael was able to track down a man

who had served on the USS Renshaw.

Tom Redinger had

been on deck the night PBY 50 went down.

He remembered

it vividly.

The reason?

PBY 50 had not crashed because its

wing struck the surface of the water in the bay.

The USS Renshaw had shot it down.

With troops being landed at night for a sneak attack at

dawn, protecting the secrecy of the operation was of paramount

concern. When the Renshaw spotted the unknown

plane, it followed protocol and immediately looked for the

automated IFF (identification, friend or foe) radio signal

that all US planes transmitted continuously in such situations.

But Schall had turned the signal off momentarily so

he could send a requested weather report. That moment had

sealed the fate of PBY 50.

On May 1, 1998, Nat and Irene Bellantoni met the Schall

family in Elderton, Pennsylvania, and placed a rose on Merle

Schall’s headstone. With that, Nat felt the sense of peace

about this beloved little plane that he had been seeking for

fifty-five years.

I’m Paul Cheall

Links

Irene died in 2016 aged 95

https://www.legacy.com/us/obituaries/bostonglobe/name/irene-bellantoni-obituary?pid=183211729

Nat's entire collection of artwork, papers, and memorabilia from World War II, resides at the Hoover Institution Library and Archives at Stanford University. Search for digital collections or use the links in the show notes.

https://digitalcollections.hoover.org/search/bellantoni

https://histories.hoover.org/battalion-artist/

My dad, John Serra, was a Seabee with the US Navy and served in Alaska, Saipan and in the invasion of Okinawa. He recorded his service and it is on the Library of Congress website Veterans History Project

http://memory.loc.gov/diglib/vhp/bib/loc.natlib.afc2001001.10960

Nancy J Spencer Denver, CO, USA

John Serra memoir

Over to another Nancy now – if you imagine I might have got confused over these Nancies, I did!

But Nancy Spencer from Denver said:

My dad, John Serra, was a Seabee with the US Navy and served in Alaska, Saipan and in the invasion of Okinawa. He recorded his service and it is on the Library of Congress website Veterans History Project http://memory.loc.gov/diglib/vhp/bib/loc.natlib.afc2001001.10960.

Listener - Just so you know, I’ve got a memoir from John coming up in a minute.

I found out that his camp was near where citizens jumped to their deaths and on one occasion a Japanese soldier ran into camp and exploded a grenade on his head.

Dad had the most amazing memory and it was so sad for me to see him ravaged by Alzheimer’s.

He died in 2016 at 94. I have a beautiful Japanese flag he brought home which I recently had framed to protect the fragile silk.

There’s a photo of the flag in the show notes and there is some Japanese writing on it, and it’s clearly a military flag because Nancy has had the writing translated. She says:

“I had a cousin who was a cloistered nun in Japan and she translated most of it for me:

In memory of landing on the string of islands between Rei Island and Ryo Island

Subtitle: A cheerful song of the Aka Island

1 The wind is fresh on Aka Mountain - the forever unshakable island of Aka!

By our conquering this most beautiful land

the land is going to prosper

- The young navy men who gather together here with one single heart

will not weaken in their courageous efforts but will go on with their duty.

- Breaking the dream - Paradise of this deserted island

the tide of culture will be swirling in it. With daily renewed strength we will

determine eternal victory

- Let us rise up all together, whipping up our drooping hearts

Let us run single mindedly towards the shore of a holy purpose

(Then a line that Nancy couldn’t translate)

The battle is ended. Peace came.

by: Masao Otau in Aka Island.

To the head of the village, Sachi Yonabuchi

Nurses Sumiko Murai Zumi and Hatsuko Yonabuchi

So it looks like this flag was a gift from some nurses? Presumably Japanese nurses?

Nancy said I know girls were pressed into serving as nurses, medical attendants etc by the Japanese Army)

And gosh, I’ve just been looking up the names of these islands. Aka island where the poem’s writer came from is near Okinawa. And Rei island is near Papua New Guinea where there was a lot of fighting and obviously where Aussie veteran Les Cooke did a lot of fighting.

So this poem is from someone based on firmly held Jap territory near Okinawa, celebrating the taking of another island near PNG. I couldn’t locate Ryo island so no matter. But Aka island is also known as hospital island would you believe?! It seems to me like the flag was a gift to the head of the village from the nurses?

Dad always made his experience sound like summer camp. I knew there had to be more to the story as I found out later from another 79th CB daughter. Dengue fever was common etc.

But hey, we are actually lucky enough to have Nancy’s Dad’s interview notes to share with you later and whilst he might not have actually been in combat, I don’t think anyone told the Japanese that! There is some thrilling action to share later on in a big PS.

Nancy thanks so much for writing in and we’ll hear from your Dad later.

BIG

Interview with John Serra [12/20/2003]

John Serra:

Interview with John Serra [12/20/2003]

Nancy Judith Serra-Spencer:

This is December the 20th, 2003, recording of John J. Serra, former SEABEE, World War II, and his Veteran experiences at that time.

79th Naval Construction Battalion (Seabees); CBMU (Naval Construction Battalion) 539

Service Location: Kodiak, Alaska; Saipan (Northern Mariana Islands); Okinawa Island (Ryukyu Islands)

Rank: Shipfitter Second Class

John Serra:

I had registered for the draft after 1942 in December. I was working at Otis Elevator where they were making crankcases for the B-29 airplanes, and the Navy officer that I met at the plant said to me, Did you register for the draft? I said, yes. He said, How would you like to go into the Navy with a rating?

I said, Gee, that sounds pretty good. Let me think about it. I thought about it for a few days, and I asked where I could sign up. He told me it was on Broad Street in Newark. I also -- he also told me I would probably get a rating since I was working at the construction business as a pipefitter helper.

So I reported to Broad Street in Newark and registered, volunteering for the Naval Construction Battalions. They told me I would receive a rating of seaman first class because I had a year or so of pipefitting background. It took a year before they called me. In the meantime, I continued to work at the construction business. I worked at several war plants and Walter Kiddie Company making fire extinguishers, also a plant where they were making machine guns and Newark Federal Shipyard, Port Shipyard, all the time doing pipe work, ___ days and weekends, anything to help the war effort.

I was finally called to active duty on early December, reported in on December the 28th. I had to report to Broadway, New York -- I forget the number -- and I had to be there at 7:00 PM. I was with a whole group of guys who were scared to death like I was. It was the first time being away from home for most of us. Probably most of us had never been out of the state nor less go to a foreign country.

We were getting our physicals, and they were reading off the names -- and they got to one fellow's name that was hard to read, and they had to use a mirror because it was printed backwards. Turned out this guy's name is Rudolph Hess, which was pretty funny because this was the time that Rudolph Hess had parachuted into England. Turned out it was not the Rudolph Hess from Hitler's Germany.

They took us by train down to Delaware, and we crossed on a ferry to Virginia. We ended up in Little Creek at Camp Bradford, which was a training camp for men who were in Naval construction. So the whole group of us had nine weeks of boot camp training then. We stayed an extended period of time -- I forgot how many days, but quite a while -- for training by marines where we had to do all kinds of exercises, live bullets shooting over us.

We had to learn how to build bunkers, how to defend ourselves. We had wrestling instructors teaching us how to wrestle. Anyway, after this all happened, we then took off by train to go to Gulfport, Mississippi to a camp called Camp Holiday. When we got there, we were told everybody on the east coast gets a nine-day boot camp leave, so we practically got on the same train back home to New Jersey, where I spent nine days with my family and friends, and then I reported back to Gulfport, Mississippi going back on the same east coast train.

We were at Gulfport for a short period of time when we were on a forced march, a 30-mile march that was very gruesome and tiring. And anybody who could not make it because of foot problems or other ailments, they were picked up and brought to the camp by truck, and those same men had to do guard duty while the rest of us got some much-needed rest. After we were there a short time, we went by train to Port Hueneme in California and did amphibious training on the beach with tool pack, which was very tough.

After we finished that, we went by train to Seattle, and we were waiting for a convoy to assemble so that we could go together and have minesweeping. We were doing the security patrol around the convoy. Most of us were pretty seasick. The water was very rough. The weather was cloudy, pretty miserable. Most of the men were seasick, and I guess out of the five days I was on the ship, I was sick four and a half. We arrived on Kodiak on Mother's Day, the 11th or 12th of May. We all were glad to get off the ship and get our land legs again. Turned out to be a very nice, beautiful day in May, although there was a bit of chill in the air, but the weather was nice.

The first assignment we had there was to straighten out the lumberyard because they had a severe storm they called the "williwaws". It blew the lumberyard apart, so they would send in all of the new recruits all over to the lumberyard to straighten out the lumber until they would assign the duties for everybody. When I first landed there, I got off the truck. I was riding with my sea bag, and I stepped on a rock and took a chip out of my ankle bone, and I ended up in the sickbay for over a month. When it was pretty well healed, they assigned me to work in a pipe shop handing materials and tools for the fellows doing the pipe work. I eventually went out and worked with the rest of the pipefitters. I worked on the rebuilding of a firehouse that settled in the ground and was all out of square and plumb so it had to be taken apart and rebuilt. I worked on nurses's homes and I worked on lots of maintenance on government housing that was there for the officers and the nurses. I also worked on water lines made of wood stave pipe and got a lot of experience doing that kind of work.

The weather on Kodiak was very severe in the winter. We would get all kinds of ice storms where we had to have cleats under our shoes because it was so icy all the time. Very windy and icy weather in the winter. We would have williwaw winds that they called them. Not a lot of snow, but a lot of ice. I lived in a wooden barracks with oil stove space heaters and inside lavatories and showers.

We didn't have a real bad life up in Alaska. There was plenty of food and movies at night during the winter. During the summer, the guys would play baseball, basketball, and different sports. We would have captain's inspection once a month at the naval air station and at the hangers. We would have to walk down a good couple of miles I guess and walk down a road that was real dusty, made of volcanic ash. It was powdery and grey, and by the time we got to the concrete apron and had to stand at attention, our clothes were not real clean anymore.

A lot of the guys were put on report because their uniforms were all dirty, but actually it was pretty difficult to keep your uniform clean while walking in the volcanic ash. Time in Kodiak was pretty good considering a lot of the other guys were fighting a war. We had it pretty good there.

We were there for about 18 months. When I first got there, we had a lot of Canadian flyers that were there, a squadron of them, I guess. They used to come over to our barracks because we had beer three or four times a week. They used to buy it at the small stores. That would bring Army and Canadian men because we had the beer. They were nice guys.

We also saw quite a few Russians that would ferry in their planes or ships from the United States to help Russia with their war effort. I worked at the submarine base, did a lot of pipefitting work and got a lot of experience. I also spent time where they had a Naval seacoast gun fighter at the seacoast of Kodiak. It was a used gun they tell me that was never fired in anger. They had test fired it, but I never actually saw it, but it was interesting to look at.

We finally left there and came home to California. Everyone was sick going to Alaska. They were good and healthy going back to the states. I guess it was because everyone was happy because they were going home on leave.

We landed in San Francisco, and within a couple of hours all of the fellows from the east coat were on a train heading for their homes, anybody east of the Mississippi, so we came home for a 30-day leave. After the 30-day leave, I reported to Quonset Point, Rhode Island. I might mention that while I was in Kodiak I did see several of the Kodiak bear, which is the largest bear in the world. They weigh only a few ounces when they're born, but they can grow to be over 2000 pounds. They're a big brown animal that eats a lot of fish, salmon mostly. And we used to see them wading in cold streams waiting until the fish were spawning in early August until late November. They would be waiting for the fish to go by and would slap the water, and that would stun the fish nearby and they would pick the fish up and take all of the meat off the bones without breaking the bones. They were big and clumsy looking, but they were very gentle in the way they fed themselves.

I also failed to mention that while in Kodiak we had the United States Army and Navy stop off before they invaded the island of Adak and Kiska that had been occupied by Japanese forces, and they were very successful in overcoming the enemy. Since the war we are in possession of Adak and Kiska. While at home on leave, I was able to visit with family and become engaged to my fiance. I reported back to Quonset Point, Rhode Island. I came home for a couple overnights and one weekend and then reported back.

We went by the northern route on a train to Camp Parks, California. We had a very interesting train ride. I remember going through the Canadian Rockies, which was beautiful with all the snow. Very picturesque. We landed on Camp Parks and did some more training there, and all of the fellows that were west of the Mississippi, they were on their leave, and when they returned we started to get ready to leave again.

The weather was really bad the night we left from San Francisco, and almost everyone got sick, including the captain of the troop ship that we were on. The weather was so rough we lost a life raft and two lifeboats, but we continued on. I was seasick I guess for 25 to 28 days I was on that ship. We stopped at the Hawaiian Islands, which was great. At least the ship wasn't moving and I started to feel better. I was not lucky enough to get off the ship, but after we were there a few days we started on our way again and continued on to Saipan Island. And we landed at night and had to unload the ship in the dark because the Japanese were still on the island and it was not secured.

We would hear gunfire frequently during the day, but at night there was a lot of gunfire because they would try to flush the Japanese out. We slept in a sugarcane field the first night, and I remember getting bit by a scorpion, and I thought I was going to die. It turned out to just be a severe bite and I didn't even receive treatment for it. We then prepared to prefabricate a lot of the material we were going to be using, and our next trip was going to be the invasion of Okinawa.

We prefabricated the entire piping system that we would need in our mess hall, which was going to be driven by steam. They were going to be cooking by steam kettles, so we had to prefabricate all the piping from the boiler to the kettles and also piping to hot water heaters they would use for cooking and washing dishes and also for showers.

We were there for about six weeks, and we started to load the LSTs. Our whole battalion fit on three ships with all our equipment, which was tremendous. We had bulldozers, cherry pickers, shovels, backhoes, and sheep's-foot, and all kinds of machines needed for road building and airport runways as well as air compressors, welding machines, refrigeration, almost everything you could think of we had on those three ships, including a whole lot of beer and Coca-Cola.

Also, while I was on an on-site plant, I worked on a water pipeline that was going to feed a Coca-Cola plant. It turned out that I met somebody who was an engineer for Coca-Cola that I had met in civilian life while working on the Coke plant on Seven Street and First Avenue in Newark, New Jersey, and it was quite interesting that I would meet this man after working at the Newark plant. He was in charge of the plant on Saipan.

When we were on our way to Okinawa after we left Saipan, one evening at about 5:00 PM while standing in line for chow -- for some unknown reason I did not get seasick on that ship. But while we were standing out looking over the water, all of the sudden a Japanese sub surfaced about 250 feet away, and a marine guard on our ship fired at the sub and hit it with an .03 rifle shell. That must have awakened the captain in the sub, and they quickly submerged.

We took off and then went so fast that almost looked like a motorboat scooting along real fast, and real fast on the steam, like eight or nine knots. It felt like we were going along really fast. We kept going and kept looking back.

We had mine sweepers and destroyer escorts as our security around our convoy. We had oil packers and all kinds of vehicles on our ships, so the fastest we could go was mainly four to five knots because the oil tankers were very slow, but it was everybody for themselves when a Japanese sub surfaced.

After we were gone maybe a half hour or so, we looked behind on the horizon and we heard a terrific explosion and saw the Jap sub surface, go down again, and was sunk. After that Japanese sub incident, we continued on and came sight of the islands of Okinawa and saw a huge smokescreen.

We couldn't see the shoreline or ships because it was all milky white. As we approached, some of the Jap planes were flying overhead. Turned out they were Kamikaze planes, suicide planes that could crash down and land on ships and hope to destroy them by setting them on fire.

We were there for three or four days before we unloaded our ship. In the meantime, the Kamikazes are coming at us for what seemed like 24 hours a day. We were completely surrounded by the milky smokescreen. On one particular day -- I think it was a Sunday – and a Kamikaze hit an LST right close to mine that was starting to unload. Luckily for us, it missed our ship and we continued to unload. This all impressed us because some of our equipment was slow moving on land, and we couldn't unload until they were further down the road. The roads were very narrow in Okinawa, and they were really like small pads, not handling the equipment that we had. The weather was not the greatest.

We had quite a bit of rain. Nobody was shooting at us other than the fact that we did have Kamikaze planes all -- all the while we were there unloading. I don't know how we missed the real bad action. The worst was that ship that was torpedoed. We did see a lot of other action where they were hitting anything they could possibly destroy.

We were unloading the ships and it continued to rain, and one day we had to use one of the doors to our ship that had been ripped off one way or another. We crashed into the beach, and the door had to be taken off. We had to use that door as a sled the bulldozer would push. We put a lot of our equipment on that because the road was so full of mud that the only thing that would move were bulldozers.